Protease Inhibitor Decision Assistant

Decision Assistant

Answer these questions to get personalized recommendations for HIV protease inhibitor alternatives to Indinavir.

Recommended Alternatives

Key Considerations

Comparison Details

| Drug | Renal Risk | Frequency | Metabolic Impact | Resistance Barrier |

|---|

Why compare Indinavir with other options?

When a clinician or a patient looks at Indinavir (Indinavir Sulphate) is a first‑generation HIV‑1 protease inhibitor approved in the mid‑1990s. It still appears in treatment guidelines for patients who can tolerate its dosing schedule, but dozens of newer protease inhibitors have entered the market. Knowing how Indinavir stacks up against those alternatives helps you avoid unwanted side effects, minimize pill burden, and keep viral load suppressed.

How Indinavir works

Indinavir binds to the active site of HIV‑1 protease, a viral enzyme needed to cut long poly‑protein chains into functional pieces. Without this cleavage, immature viral particles can’t mature, and the infection stalls. The drug is taken on an empty stomach, usually 800 mg three times a day, because food drastically reduces its absorption.

Key players in the protease‑inhibitor class

Below are the most common alternatives you’ll encounter in modern regimens. Each has its own dosing convenience, resistance profile, and side‑effect fingerprint.

- Saquinavir - older, requires a boosting agent (ritonavir) for adequate blood levels.

- Lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra) - co‑formulated booster, taken twice daily.

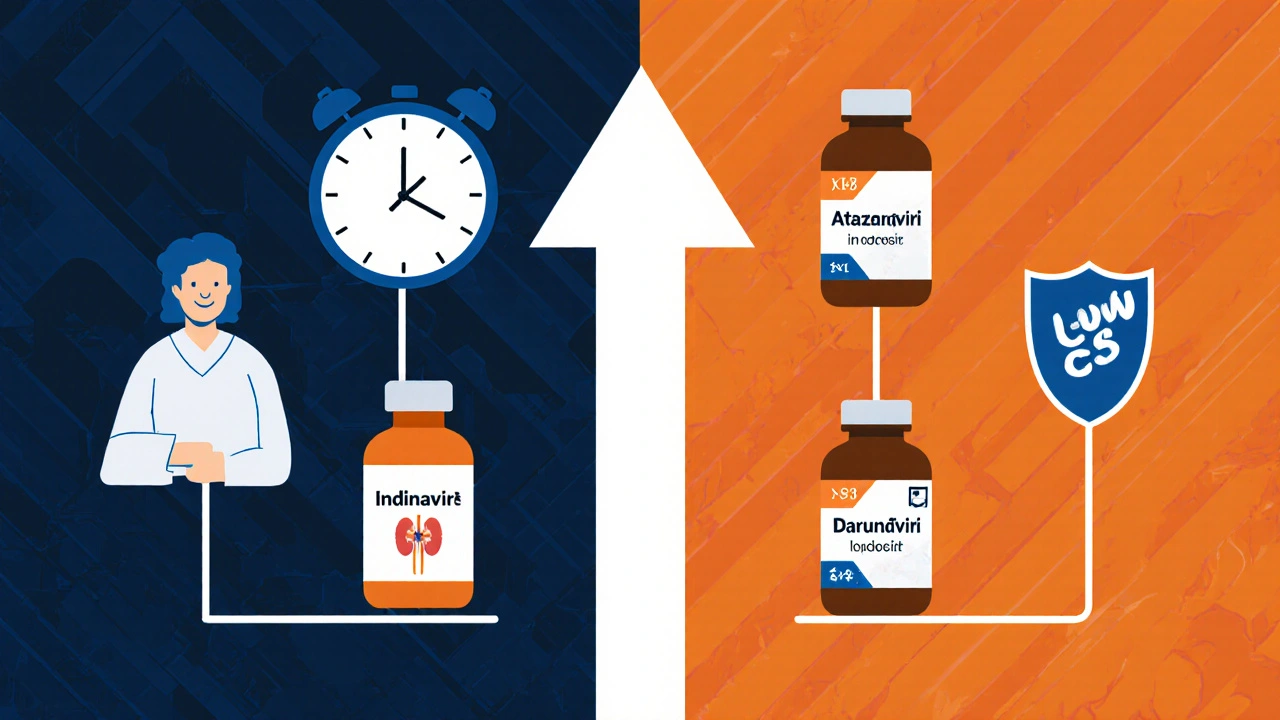

- Atazanavir - once‑daily option, low impact on lipid profile.

- Darunavir - high barrier to resistance, often paired with ritonavir.

- Nelfinavir - older, taken with food, notable for skin rash.

- Fosamprenavir - pro‑drug of amprenavir, taken with food.

Side‑effect landscape

Indinavir is notorious for kidney stones (crystalluria) and hyperbilirubinemia. In contrast, atazanavir often causes mild jaundice, while lopinavir/ritonavir is linked to dyslipidemia and insulin resistance. Darunavir tends to have the most tolerable metabolic profile but can still cause diarrhea when boosted.

Detailed comparison table

| Attribute | Indinavir | Saquinavir (boosted) | Lopinavir/ritonavir | Atazanavir (boosted) | Darunavir (boosted) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose frequency | 800 mg TID (empty stomach) | 1000 mg BID + ritonavir | 400/100 mg BID | 300 mg QD + ritonavir | 800 mg QD + ritonavir |

| Food effect | Food reduces absorption 50% | Must be taken with food | Can be taken with or without food | Food‑independent | Food‑independent |

| Renal toxicity | High (crystalluria, stones) | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Metabolic impact | Modest lipid rise | Moderate lipid rise | Significant dyslipidemia | Minimal lipid change | Low lipid effect |

| Resistance barrier | Low (early‑generation) | Moderate | Moderate | High | Very high |

| Common adverse events | Kidney stones, jaundice, lipodystrophy | GI upset, rash | Diarrhea, nausea, hyperglycemia | Jaundice, mild GI upset | Diarrhea, headache |

When to stay with Indinavir

If a patient has already achieved viral suppression on Indinavir, tolerates the drug, and has no history of kidney stones, there’s little reason to switch. Some insurance formularies still list Indinavir as a lower‑cost option, making it attractive when cost is a decisive factor.

When to consider an alternative

Switch is advisable if any of the following arise:

- Recurrent nephrolithiasis or unexplained hematuria.

- Difficulty adhering to a three‑times‑daily regimen.

- Emergence of resistance mutations that affect Indinavir’s binding pocket.

- Unacceptable metabolic changes (elevated triglycerides, insulin resistance).

In such cases, atazanavir or darunavir provide once‑daily dosing and a better metabolic profile. Lopinavir/ritonavir remains a solid choice when a strong booster effect is needed for other agents.

Practical monitoring tips

- Baseline kidney function: serum creatinine, eGFR, and urine analysis for crystals.

- Every 3‑6 months: fasting lipid panel, fasting glucose, and bilirubin.

- Adherence check: pill count or pharmacy refill data, especially with TID dosing.

- Resistance testing: performed if viral load rebounds >200 copies/mL.

Document any side effects promptly; early intervention can prevent permanent organ damage.

Bottom line

Indinavir still has a niche but Indinavir alternatives such as atazanavir or darunavir dominate modern therapy because they simplify dosing, spare the kidneys, and resist resistance. The right choice hinges on individual patient factors-renal health, pill burden tolerance, metabolic risk, and insurance coverage.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I switch from Indinavir to another protease inhibitor without a treatment break?

Yes. Most clinicians perform a direct switch, maintaining a continuous regimen to avoid viral rebound. However, a short overlap with a boosting agent (ritonavir) may be required if the new drug needs it.

Why does Indinavir cause kidney stones?

Indinavir is poorly soluble in urine; when concentrations rise, it can crystallize and form stones, especially if patients stay dehydrated.

Is food restriction a major drawback?

The need to fast for at least one hour before and after each dose can be inconvenient, especially for people with irregular schedules. Newer agents have no such restriction.

How does resistance to Indinavir develop?

Mutations in the HIV‑1 protease active site (e.g., D30N, I50V) reduce binding affinity. Because Indinavir has a lower genetic barrier, fewer mutations are needed for failure compared with darunavir.

Which alternative has the lowest impact on cholesterol?

Atazanavir, especially when boosted with ritonavir, shows the smallest rise in LDL and triglycerides among the listed protease inhibitors.

8 Comments

Harry Bhullar-21 October 2025

Indinavir’s pharmacokinetic profile really sets the stage for why clinicians still keep it in the toolbox, especially when you consider its three-times‑daily dosing and the strict empty‑stomach requirement which sometimes forces patients to plan their meals around medication times. The drug’s low barrier to resistance means that mutational pathways can emerge quickly if adherence slips even for a short period, and those mutations, such as D30N or I50V, can significantly reduce viral suppression. On the other hand, the renal toxicity profile, highlighted by crystalluria and nephrolithiasis, can be mitigated by ensuring patients stay well‑hydrated and have regular urine analyses. Compared with saquinavir, which needs ritonavir boosting and food intake, indinavir’s absorption is far more sensitive to food, leading to a roughly 50 % drop in bioavailability when taken with meals. Lopinavir/ritonavir, while convenient twice daily, carries a heavier metabolic burden, often raising LDL and triglycerides to clinically concerning levels. Atazanavir, especially in its boosted form, shines in lipid sparing but can still produce mild hyperbilirubinemia, which is generally well tolerated. Darunavir stands out with its very high genetic barrier, making it a go‑to when resistance mutations accumulate, but its cost can be prohibitive in some health systems. In practice, a clinician must weigh the pill burden, metabolic side‑effects, renal considerations, and insurance formularies before deciding whether to keep a patient on indinavir or transition them. Monitoring should include baseline creatinine, eGFR, and periodic lipid panels every three to six months, plus resistance testing if viral load rebounds above 200 copies/mL. Patient education about the importance of fasting before and after each dose cannot be overstated, as non‑adherence to this schedule leads to subtherapeutic levels and possible virologic failure. When patients can tolerate the regimen without kidney stones and have stable viral loads, indinavir remains a cost‑effective option, especially in resource‑limited settings. However, the modern trend leans toward once‑daily agents that simplify adherence and reduce metabolic complications, which improves long‑term outcomes for many individuals living with HIV. Overall, the choice hinges on a nuanced assessment of renal health, metabolic risk, resistance patterns, and socioeconomic factors, all of which must be individualized for each patient.

Dana Yonce-22 October 2025

Indinavir is great if you don’t mind the extra trips to the bathroom for water 😉. The kidney stone thing can be scary, but drinking lots of fluids helps a lot. Also, the fasting rule can be a pain if you have a busy schedule.

Sakib Shaikh-25 October 2025

Yo, let me tell ya, indinavir is like the drama king of HIV meds – it loves to throw kidney stones at you if u ain't drinking enough water! And the whole empty stomach thing? U gotta fast like a monk before every dose, or else the drug just won't work right. It's definetly not for the lazy, but some peeps still love it cause it's cheap and they got it covered by insurance. But seriously, watch out for that jaundice, it can turn your skin yellow like a banana, and that lipodystrophy can mess up your body shape. If u can handle the hassle, it's still in the game, but there's newer stuff that's way smoother on the kidneys and easier on the schedule.

Chirag Muthoo-27 October 2025

Indinavir remains a viable therapeutic option within certain clinical contexts, particularly where cost considerations predominate and the patient demonstrates stable renal function without a history of nephrolithiasis. Nevertheless, the necessity for administration in a fasted state imposes a notable inconvenience, and the drug’s relatively low resistance barrier warrants vigilant virological monitoring.

Angela Koulouris-29 October 2025

Hey there, just wanted to add that while indinavir can be a bit of a hassle with its dosing schedule, it also offers an opportunity for patients to develop a disciplined routine that can empower them in managing their overall health. Think of it as a training ground for self‑care, where staying hydrated and mindful of food timing becomes a positive habit.

Lolita Gaela- 1 November 2025

The pharmacodynamic profile of indinavir, characterized by its protease inhibition constant (Ki) and the resultant impact on viral polyprotein processing, underscores its utility in regimens where high plasma concentrations can be achieved despite the high first‑pass metabolism. However, its limited bioavailability under fed conditions necessitates strict adherence to fasting protocols to maintain optimal trough levels (Cmin), thereby reducing the risk of subtherapeutic exposure and emergent resistance mutations. Comparative pharmacokinetic studies demonstrate that boosted atazanavir and darunavir achieve superior area under the curve (AUC) metrics with more favorable lipid panels, which may influence regimen selection in patients with dyslipidemia.

Kimberly Lloyd- 4 November 2025

Staying hopeful, we can tailor therapy to each life story.

Giusto Madison- 8 November 2025

While your overview is thorough, don’t overlook the cost factor that still makes indinavir relevant in many formularies. Also, make sure patients get proper counseling on hydration to avoid those pesky kidney stones.