- Both conditions affect the inner ear’s balance and hearing functions.

- Inflammation or fluid buildup can trigger or worsen symptoms.

- Accurate diagnosis hinges on distinguishing infection signs from Meniere’s episodes.

- Treating an infection may reduce vertigo frequency for many patients.

- Lifestyle changes and early medical care improve long‑term outcomes.

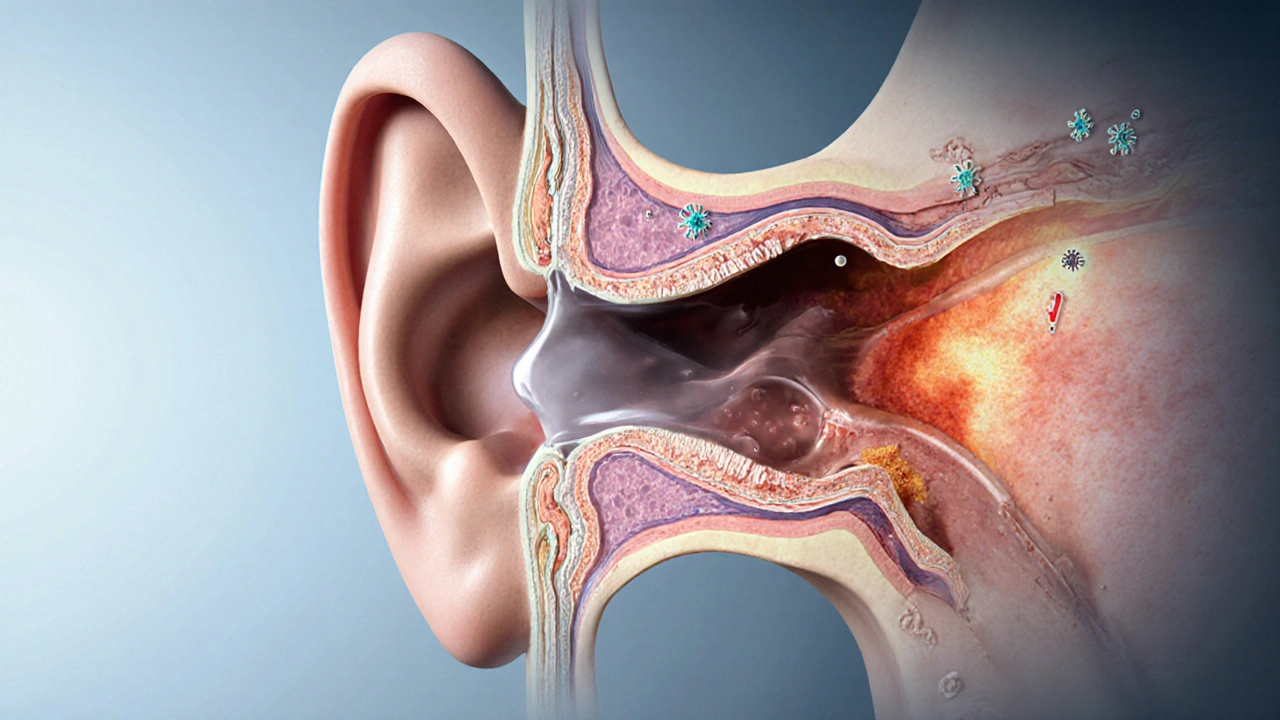

When exploring hearing disorders, Meniere's disease is a chronic inner‑ear condition marked by recurrent vertigo, fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus and a sensation of ear fullness. At the same time, inner ear infection refers to an inflammatory process that can involve the cochlea, vestibular labyrinth or both, often caused by bacteria or viruses. While they sound distinct, many patients discover that an infection can ignite or aggravate a Meniere’s episode. Below, we unpack the biology, the diagnostic maze, and practical steps you can take.

What is Meniere's disease?

First described in the 19th century, Meniere's disease is linked to endolymphatic hydrops - a buildup of the fluid (endolymph) inside the vestibular system’s membranous labyrinth. The excess pressure disrupts the hair cells that translate motion into nerve signals, resulting in the classic triad of vertigo, tinnitus and fluctuating sensorineural hearing loss. Episodes typically last from a few minutes to several hours, followed by a period of remission that can span weeks or months.

Key attributes of Meniere's disease:

- Unpredictable vertigo attacks.

- Low‑frequency hearing loss that may become permanent.

- Tinnitus that often mirrors the affected ear.

- Aural fullness or pressure sensation.

Statistics from the American Academy of Otolaryngology indicate that roughly 12 per 100,000 adults develop the disorder, with most cases appearing between ages 40 and 60.

What are inner ear infections?

Inner ear infections, medically termed labyrinthitis (viral) or otitis interna (bacterial), involve inflammation of the delicate structures that manage balance and hearing. Common culprits include influenza, the common cold, and bacterial agents like Streptococcus pneumoniae. When pathogens infiltrate the cochlea or the semicircular canals, they provoke swelling, disrupt ionic gradients, and can temporarily impair auditory and vestibular function.

Typical signs of an inner ear infection:

- Sudden onset of dizziness or spinning sensation.

- Hearing loss that may be conductive, sensorineural, or mixed.

- Ear pain or pressure, sometimes with fever.

- Nausea, vomiting, and loss of balance.

Acute infections usually resolve within two weeks with appropriate care, but lingering inflammation can set the stage for chronic inner‑ear issues.

How the two conditions intersect

Both maladies share the vestibular system as a central player. Inflammation from an infection can increase endolymph volume, directly feeding into the hydrops that characterizes Meniere’s disease. Researchers at the University of Sydney (2023) observed that patients with a recent viral labyrinthitis were twice as likely to experience a first‑time Meniere’s episode within six months.

Key pathways linking them:

- Fluid imbalance: Infection‑induced edema raises endolymphatic pressure, mimicking the hydrops state.

- Immune response: Cytokine release (e.g., IL‑1β, TNF‑α) can damage hair cells, lowering the threshold for vertigo attacks.

- Vascular compromise: Infections may narrow the labyrinthine artery, reducing blood flow and exacerbating inner‑ear stress.

Consequently, treating the infection often dampens the severity or frequency of Meniere’s episodes.

Diagnosing the overlap

Because symptoms overlap, clinicians rely on a combination of patient history, audiometric testing, and imaging to tease the conditions apart.

Diagnostic checklist:

- Symptom chronology: Infections typically present with fever, ear pain, and rapid onset dizziness; Meniere’s attacks are more episodic without systemic signs.

- Pure‑tone audiometry: Meniere’s shows low‑frequency loss that fluctuates; infection‑related loss may be flat or high‑frequency.

- Electronystagmography (ENG) or video‑head‑impulse test (vHIT): Abnormal vestibular reflexes point to labyrinthitis.

- CT/MRI: Imaging rules out structural lesions but can reveal fluid accumulation suggestive of hydrops.

When in doubt, a trial of antibiotics or antivirals can serve both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes-improvement supports an infectious component.

Managing both conditions

Effective management hinges on addressing the infection first, then stabilizing the inner‑ear environment to control Meniere’s symptoms.

Short‑term infection care

- Antibiotics: For bacterial otitis interna, a high‑dose course of ceftriaxone or amoxicillin‑clavulanate is standard.

- Antivirals: In cases of confirmed viral labyrinthitis, agents like acyclovir may be prescribed.

- Corticosteroids: Oral or intratympanic steroids reduce inflammation and can limit permanent hair‑cell damage.

Long‑term Meniere’s control

- Low‑salt diet: Limiting sodium to < 1500mg/day helps regulate endolymph volume.

- Diuretics: Agents such as hydrochlorothiazide promote fluid drainage.

- Vestibular rehabilitation: Tailored exercises improve balance compensation after attacks.

- Gentamicin injections: In refractory cases, locally‑administered gentamicin selectively ablates vestibular hair cells, reducing vertigo without full hearing loss.

Patients who clear an infection often report fewer severe vertigo spells within the first three months, underscoring the importance of timely antimicrobial therapy.

Prevention and lifestyle tips

Even if you’ve never experienced an inner‑ear infection, adopting ear‑friendly habits can lower the odds of triggering a Meniere’s flare.

- Stay up‑to‑date with flu and pneumonia vaccinations.

- Avoid prolonged exposure to loud noises; use ear protection when needed.

- Manage stress through meditation or gentle yoga-stress hormones can affect inner‑ear fluid regulation.

- Limit caffeine and alcohol, both of which can alter blood flow to the inner ear.

Regular check‑ups with an ENT specialist are advisable for anyone with a history of vertigo or hearing loss.

Quick reference checklist

| Symptom | Typical for Meniere's | Typical for Infection |

|---|---|---|

| Vertigo attacks | Recurrent, lasting minutes‑hours | Sudden, often accompanied by nausea |

| Hearing loss | Fluctuating low‑frequency loss | Rapid onset, may affect high frequencies |

| Tinnitus | Constant ringing in affected ear | May be present but less prominent |

| Ear pain/pressure | Fullness sensation, no sharp pain | Sharp pain, possible fever |

| Systemic signs | None | Fever, malaise |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can an inner ear infection cause Meniere's disease?

Yes. Inflammation from an infection can increase endolymphatic pressure, a key factor in developing the hydrops that underlies Meniere's disease. Treating the infection early can reduce the risk of a chronic Meniere’s pattern.

How long does it take for vertigo to improve after antibiotics?

Most patients notice a reduction in dizziness within 3‑5 days of starting a proper antibiotic regimen, though full resolution may take up to two weeks depending on the severity of the infection.

Is low‑salt diet enough to control Meniere's attacks?

A low‑salt diet helps manage fluid balance but is usually combined with diuretics, stress‑reduction techniques, and sometimes vestibular therapy for optimal control.

When should I see an ENT specialist?

If you experience sudden hearing loss, persistent vertigo, or ear pain accompanied by fever, schedule an appointment within 24‑48hours. Even milder, recurrent episodes merit a specialist visit to rule out Meniere's disease.

Can vestibular rehabilitation cure Meniere's disease?

Rehabilitation does not cure the underlying fluid imbalance, but it trains the brain to compensate for balance disturbances, reducing fall risk and improving daily function.

12 Comments

Veronica Rodriguez- 2 October 2025

It's great to catch early signs of an inner‑ear infection because starting antibiotics or antivirals promptly can keep a Meniere’s flare from taking off 😊. Keep track of any sudden ear pressure, fever, or nausea and get to your ENT within 24‑48 hours. A low‑salt diet and regular vestibular exercises also help the ear recover faster.

Catherine Zeigler- 2 October 2025

First off, I want to say that navigating the overlap between Meniere’s disease and labyrinthitis can feel like trying to solve a puzzle with pieces that keep shifting, but you’re definitely not alone in this journey. Understanding that both conditions share the vestibular system is the foundation for a solid management plan, and recognizing the subtle differences in symptom onset can guide you toward the right doctor. When you notice a fever or ear pain that comes on rapidly, that’s a flag that an infection is likely in play, whereas the classic episodic vertigo without systemic signs points more toward Meniere’s. It’s amazing how a simple saline rinse and staying hydrated can keep the inner‑ear fluids balanced, and those small habits add up over time. Pairing a low‑salt diet with a modest diuretic can reduce the endolymphatic pressure that fuels the hydrops, which is a cornerstone of long‑term control. If you’ve already been prescribed steroids, remember that tapering them under supervision prevents rebound inflammation that could otherwise trigger another vertigo spell. Vestibular rehabilitation isn’t a quick fix, but the targeted exercises train your brain to compensate for the vestibular loss, making daily activities feel safer. Many patients report that after a thorough infection treatment, the frequency of Meniere’s attacks drops significantly, reinforcing the importance of early antimicrobial therapy. Keep an eye on any changes in your hearing thresholds; even a slight shift can signal that the inner‑ear environment is reacting to inflammation. Staying up‑to‑date with flu and pneumonia vaccines is a proactive step that many overlook, yet it can cut down the risk of viral labyrinthitis that often precedes a Meniere’s episode. Stress management is another piece of the puzzle – chronic cortisol spikes can affect fluid regulation in the ear, so incorporating meditation or gentle yoga can be surprisingly beneficial. Alcohol and caffeine moderation isn’t just a lifestyle suggestion; both substances can alter blood flow and fluid balance in ways that worsen vertigo. Regular check‑ups with an ENT who’s familiar with both conditions ensure that any subtle changes are caught early, and imaging studies can help differentiate fluid buildup from other structural issues. If you ever feel overwhelmed, reaching out to a support community can provide practical tips and emotional reinforcement, which is vital for staying motivated. Lastly, be patient with yourself – recovery and control are gradual processes, and each small step you take builds toward a steadier, quieter inner ear.

henry leathem- 2 October 2025

The pathophysiology underlying labyrinthine inflammation is fundamentally a cascade of cytokine-mediated endolymphatic perturbations, which, in the presence of pre‑existing hydrops, precipitates a maladaptive vestibular response; the literature unequivocally demonstrates that untreated otitis interna serves as a potentiating factor for Meniere’s phenoconversion. Moreover, the ototoxicity profile of systemic aminoglycosides, when juxtaposed with the pharmacodynamics of diuretics, necessitates a calibrated therapeutic regimen to avert iatrogenic cochlear insult. Clinicians who dismiss these mechanistic intricacies are, frankly, operating with a perilously superficial understanding of otologic medicine.

jeff lamore- 2 October 2025

I appreciate the detailed breakdown you’ve shared, and I think it’s important to highlight that patient education plays a pivotal role in management. Explaining the distinction between infection‑driven vertigo and Meniere’s episodes can empower individuals to seek appropriate care promptly. While the medical jargon can be daunting, a clear conversation about treatment options-antibiotics, steroids, or vestibular therapy-helps set realistic expectations.

Kris cree9- 2 October 2025

Oh my god, I can’t even… this whole thing sounds like a tragedy waiting to happen! People are out there ignoring the signs, drinking coffee, eating salty snacks, and then-boom-vertigo hits like a truck. It’s like they’re asking for disaster, and nobody’s gonna fix it if they keep playing dumb. Seriously, get your act together!

Paula Hines- 2 October 2025

When we contemplate the inner ear we are, in effect, peering into a microcosm of balance and perception a realm where fluid dynamics echo the broader currents of existence the ebb and flow of endolymph mirrors the tides of human emotion and disturbance there is a silent dialogue between physiology and philosophy that often goes unremarked the moment a patient feels the sudden spin of vertigo it is as if the world tilts within the very core of their being inviting us to consider how the smallest imbalance can cascade into profound disarray yet within that same delicate system lies the capacity for remarkable adaptation through vestibular rehabilitation this therapeutic dance of neuroplasticity rewires pathways and restores equilibrium it is a testament to the resilience embedded in our biology the pursuit of low‑salt diets and stress reduction is not merely a prescription but a metaphor for the harmonization of internal and external forces that govern health and life

John Babko- 2 October 2025

Absolutely, the connection is crystal clear, and you must remember, friends, that early intervention, aggressive treatment, and diligent lifestyle changes-yes, all three-are the pillars that hold the whole structure together, otherwise you risk a cascade of symptoms, which no one wants!

Stacy McAlpine- 2 October 2025

The key takeaway is to treat any ear infection right away and keep your salt intake low, because that can really cut down how often Meniere’s attacks happen.

Roger Perez- 2 October 2025

Think of the ear as a tiny orchestra 🎶-when an infection shows up, it’s like a rogue instrument playing out of tune, and the whole symphony of balance can wobble. By clearing that infection you’re letting the music return to harmony, which is why early antibiotics feel like a conductor stepping in to restore the rhythm 😊.

michael santoso- 3 October 2025

While the overview is undeniably thorough, it borders on pedantic recursion; a more succinct synthesis would better serve readers who lack a specialist’s endurance for exhaustive exposition.

M2lifestyle Prem nagar- 3 October 2025

Stay hydrated and watch your salt.

Karen Ballard- 3 October 2025

Great summary! Just a tip: “vertigo” is usually uncountable, so say “episodes of vertigo” 😊.