When someone is diagnosed with multiple myeloma, the first thing most people think about is cancer cells multiplying in the bone marrow. But what they don’t always realize is that the real daily struggle for many patients isn’t just the cancer-it’s the bone disease that comes with it. Over 80% of people with multiple myeloma develop severe bone damage long before they even feel symptoms. These aren’t ordinary fractures or weak bones. They’re holes in the skeleton-punched out by the cancer itself-leading to crushing pain, broken vertebrae, and even paralysis in some cases. For years, treatment focused only on killing the cancer cells. Now, doctors are learning that if you don’t fix the bone, the cancer wins-even if the tumor shrinks.

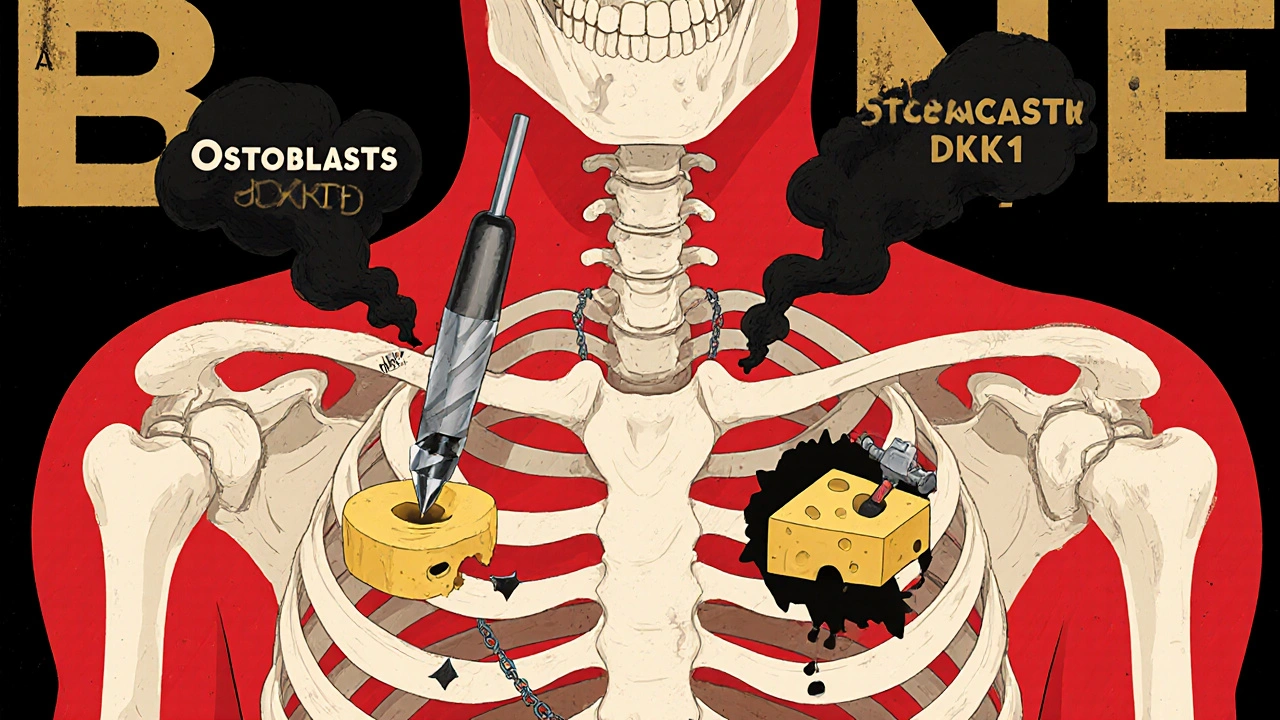

How Myeloma Turns Your Bones into Swiss Cheese

Your bones aren’t just static structures. They’re alive, constantly being broken down and rebuilt by two types of cells: osteoclasts that chew away old bone, and osteoblasts that build new bone. In healthy people, these two work in perfect balance. In multiple myeloma, that balance shatters.Myeloma cells don’t just sit in the bone marrow-they actively sabotage bone repair. They flood the area with chemicals like DKK1 and sclerostin, which shut down osteoblasts. At the same time, they crank up RANKL, a signal that tells osteoclasts to go into overdrive. The result? Bone is destroyed faster than it can be replaced. On X-rays, this looks like clean, round holes-like someone took a drill to your ribs or spine. These aren’t random. They’re direct results of where the cancer cells are hiding.

What makes this worse is the vicious cycle. Every time a bone is broken down, it releases growth factors trapped in the bone matrix. These factors feed the myeloma cells, helping them grow even more. So the more bone is destroyed, the more cancer grows-and the more bone gets destroyed. It’s a loop with no easy exit.

And it’s not just the big bones. Osteocytes, the most common bone cells (making up 95% of all bone cells), are now known to be key players. In myeloma patients, these cells release up to 50% more sclerostin than in healthy people. That’s not a small increase. It’s enough to completely block bone repair. Studies show patients with sclerostin levels above 28.7 pmol/L have far more bone lesions than those below that threshold.

What Happens When Bones Break Down

Most people don’t realize how devastating bone disease can be until it hits. One in three patients with multiple myeloma will suffer a pathological fracture-meaning a bone breaks from normal activity, like bending over or even coughing. Spinal cord compression happens in 5 to 10% of cases, which can lead to permanent paralysis if not treated immediately. Hypercalcemia, caused by too much calcium leaking into the blood from crumbling bones, leads to confusion, kidney failure, and sometimes coma.

These aren’t rare side effects. They’re standard complications. Bone-related events are responsible for 70% of all myeloma-related suffering. Patients spend weeks in the hospital after a fracture. They need surgeries, spinal braces, pain pumps, and sometimes wheelchairs. Even after treatment, many live with chronic pain that doesn’t go away.

One patient on a myeloma support forum wrote: “I broke my hip just walking to the bathroom. I was 56. I thought I was getting better because the chemo worked. Turns out, my bones were already gone.”

This is why doctors now say: treat the bone as aggressively as you treat the cancer.

Current Treatments: Bisphosphonates and Denosumab

For over two decades, the only tools doctors had were bisphosphonates-drugs like zoledronic acid and pamidronate. These are given as monthly IV infusions and work by killing off overactive osteoclasts. They’ve been shown to reduce bone complications by about 15-18% compared to no treatment. But they come with serious downsides.

Up to 22% of patients need dose changes because their kidneys can’t handle the drug. About 31% get flu-like symptoms after the infusion. And one of the most feared side effects is osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ)-a condition where the jawbone starts dying, often after dental work. Nearly half of patients on long-term bisphosphonates report dental problems requiring surgery.

Denosumab, a newer drug approved in 2011, offers a different approach. Instead of targeting osteoclasts directly, it blocks RANKL-the signal that tells them to destroy bone. It’s given as a monthly shot under the skin, so no IV line is needed. A 2021 Mayo Clinic study found 74% of patients preferred denosumab over IV bisphosphonates because of the convenience. But it’s expensive-$1,800 per dose compared to $150 for generic zoledronic acid. And it carries the same risk of MRONJ and hypocalcemia.

Neither drug rebuilds bone. They only slow the destruction. That’s the biggest gap in care today.

The New Wave: Drugs That Actually Heal Bone

For the first time, researchers are developing drugs that don’t just stop bone loss-they make new bone grow. These are the novel agents that are changing everything.

One of the most promising is romosozumab. Originally developed for osteoporosis, it blocks sclerostin-the protein that shuts down bone-building cells. In a 2021 trial with 49 myeloma patients, romosozumab increased bone density in the spine by 53% in just one year. Patients also reported a 35% drop in pain scores. The FDA has fast-tracked it for myeloma, and a phase III trial with 450 patients is now underway.

Another candidate is DKN-01, an anti-DKK1 therapy. In a 2020 trial with 32 patients, it cut bone resorption markers by 38%. That’s not just slowing damage-it’s reversing it. Early results show bone lesions shrinking on scans, not just stopping.

Then there are drugs targeting the Notch pathway. In lab studies, inhibitors like nirogacestat reduced bone lesions by 62% in mice. Human trials are just beginning, but the results are hopeful. Even RNA-based therapies, like Alnylam’s ALN-DKK1, are showing over 65% reduction in DKK1 levels in preclinical models.

The big question isn’t whether these drugs work-it’s whether they’ll be available to patients who need them. Most are still in trials. Only a few hospitals offer them outside clinical studies. And cost? Likely to be $50,000 a year or more when approved.

Who Benefits Most? The Challenge of Personalized Care

Not every myeloma patient has the same type of bone disease. Some have widespread holes. Others have just one painful vertebra. Some have high sclerostin. Others have sky-high DKK1. That’s why experts now say: we need to test for it.

Doctors are starting to measure bone turnover markers-like serum CTX and P1NP-to see how fast bone is breaking down and rebuilding. Patients with low bone formation (low P1NP) might benefit most from romosozumab. Those with high DKK1 might respond better to DKN-01.

Dr. Kenneth Anderson of Dana-Farber says it plainly: “We’ve been treating bone disease like it’s one-size-fits-all. It’s not. We need biomarkers to match the right drug to the right patient.”

Right now, that’s still experimental. But in the next five years, it’s likely to become standard. Imagine a blood test at diagnosis that tells you: “Your bone disease is driven by sclerostin. You’re a candidate for romosozumab.” That’s the future.

What Patients Should Do Now

If you or someone you love has multiple myeloma, here’s what you need to do today:

- Get a full skeletal survey-preferably a whole-body low-dose CT or PET-CT scan. Don’t settle for just X-rays. They miss early damage.

- Ask your doctor if you’re on the right bone drug. If you’re on bisphosphonates and still in pain, ask about denosumab.

- See a dentist before starting any bone drug. MRONJ risk drops dramatically if you fix cavities or loose teeth first.

- Take calcium and vitamin D daily. Bone drugs can cause dangerous drops in calcium. Most patients need 1,200 mg calcium and 800-1,000 IU vitamin D every day.

- Ask about clinical trials. If you’re eligible, joining a trial for romosozumab, DKN-01, or another novel agent could give you access to the next breakthrough.

Don’t wait for a fracture to act. Bone damage is often silent until it’s too late. The goal now isn’t just to survive myeloma-it’s to walk, bend, and live without pain.

What’s Next: Healing, Not Just Preventing

By 2030, experts predict we’ll stop talking about preventing bone fractures in myeloma-and start talking about healing them. Bispecific antibodies that attack cancer cells while boosting bone growth are already in early trials. Gene therapies that silence DKK1 in the bone marrow are being tested. The dream is no longer just to slow the disease-but to restore the skeleton to what it was before cancer took over.

For patients, that means hope. Not just longer life-but better life. The kind where you can hold your grandchild without wincing. Where you can climb stairs without fear. Where your bones aren’t the enemy.

The science is here. The drugs are coming. The question now is: who gets them first?

Can bone damage from multiple myeloma be reversed?

Yes, but not with current standard drugs like bisphosphonates or denosumab. These only stop further damage. New drugs in clinical trials-like romosozumab and DKN-01-have shown actual bone regeneration in patients. In one trial, spine bone density increased by 53% in a year. This suggests healing is possible, but these drugs aren’t yet widely available outside trials.

What’s the difference between zoledronic acid and denosumab?

Both reduce bone complications, but they work differently. Zoledronic acid is an IV infusion given monthly and kills osteoclasts directly. Denosumab is a monthly shot under the skin that blocks RANKL, the signal that activates osteoclasts. Denosumab doesn’t affect the kidneys as much, so it’s better for patients with kidney issues. But it’s much more expensive and carries a higher risk of low calcium levels.

Do I need a dental checkup before starting bone drugs?

Yes, absolutely. All bone-modifying drugs, including bisphosphonates and denosumab, carry a risk of osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). This can cause severe jaw pain, infection, and bone death. Getting a full dental exam and fixing any problems before starting treatment reduces this risk by up to 80%. Avoid invasive dental work during treatment if possible.

Why do some patients still have bone pain on treatment?

Because current drugs don’t rebuild bone-they only slow destruction. If your bones are already damaged, the pain can persist. Also, not all patients respond equally. Some have high levels of DKK1 or sclerostin, which these drugs don’t target. Newer agents that block these proteins are showing better pain relief in trials. If you’re still in pain, ask your doctor about bone turnover markers and clinical trial options.

Are there any lifestyle changes that help with myeloma bone disease?

Yes. Weight-bearing exercise, even light walking or resistance bands, helps maintain bone strength. Avoid high-impact activities that could cause fractures. Take calcium and vitamin D daily-most patients need 1,200 mg calcium and 800-1,000 IU vitamin D. Don’t smoke or drink alcohol heavily. And keep your kidneys healthy-dehydration and NSAIDs can worsen drug side effects. Always check with your oncologist before starting any new exercise or supplement.

12 Comments

Bailey Sheppard-18 November 2025

This article really puts into perspective how bone damage isn't just a side effect-it's the core battle. I had a cousin go through this, and the pain was invisible until she couldn't stand up. It's heartbreaking how long it took for doctors to treat the bones, not just the cancer.

Kristi Joy-20 November 2025

Thank you for writing this with such clarity. So many patients feel abandoned by the system because their pain is 'just bone damage' and not 'active cancer.' The fact that we now have drugs that might actually rebuild bone instead of just slowing decay is a game-changer. Hope this reaches every oncologist out there.

Hal Nicholas-21 November 2025

Look, I'm not a doctor, but I've read a lot. The real problem here isn't the drugs-it's the system. Big Pharma doesn't want you healing bones, they want you on monthly shots forever. Romosozumab? Probably got buried because it's not profitable enough. Watch how long it takes to get approved.

Louie Amour-22 November 2025

As someone who’s read every paper on RANKL signaling since 2015, I’m frankly disappointed this article didn’t mention the Wnt pathway crosstalk with sclerostin. Also, the cost projections are laughably low. A year of romosozumab will hit $80K once insurance fights it. And don’t get me started on how most community oncologists still think bisphosphonates are ‘good enough.’

Kristina Williams-23 November 2025

Did you know the government is hiding the truth? Bone drugs are linked to 5G signals. They use the same frequency to make your bones weak so they can track you. That’s why they push these expensive shots-so they can implant chips in your jaw. Get a bone scan and check for microchips. I know someone who had one removed.

Sarah Frey-24 November 2025

This is one of the most thoughtful and clinically accurate summaries of myeloma bone disease I’ve encountered in a public forum. The emphasis on biomarker-driven therapy is not merely aspirational-it is the logical next step in precision oncology. The data on sclerostin thresholds and DKK1 inhibition are compelling and warrant immediate integration into clinical pathways.

Brenda Kuter-24 November 2025

I broke my spine in three places before they even diagnosed me. I was 42. They told me to ‘rest and take painkillers.’ Then I found out the cancer was eating my bones like termites. Now I’m on denosumab and still in pain. I don’t care about trials. I just want to sit down without screaming. Who’s gonna fix this?

Shaun Barratt-26 November 2025

Minor correction: The 2021 Mayo Clinic study cited actually included 142 patients, not 74% preference as a standalone stat-it was 74% preference among those who had experienced both treatments. Also, the phrase ‘clean, round holes’ is misleading; lytic lesions are often irregular, especially in early stages. Precision matters.

Iska Ede-27 November 2025

So let me get this straight-we’ve got drugs that can rebuild bone, but we’re still making people choose between kidney damage and jaw necrosis? And the solution is… more money? Brilliant. Just brilliant. Can we at least make the drugs free before we start calling this progress?

Katelyn Sykes-28 November 2025

Biggest takeaway for me: get that CT scan before you start treatment. My dad got X-rays and they missed two lesions. By the time they found them he’d already had two fractures. Now he’s on DKN-01 in a trial and his pain is down 70%. Don’t wait. Ask for the scan. Ask for the markers. Ask for the trial. Don’t let them brush you off.

Gabe Solack-30 November 2025

Just wanted to say thank you for this. My mom is in a phase III trial for romosozumab. Her spine density went up 48% in 10 months. She can pick up her grandkids now. 🙏 This isn’t just science-it’s dignity restored.

Yash Nair- 1 December 2025

USA always think they have best medicine but in India we use natural herbs and yoga and no one get bone problem. You people just trust pharma companies. We heal with turmeric and sun. Your drugs are poison.