When you’re running a clinical trial, every patient reaction matters. But not every reaction needs to be reported the same way. The difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one isn’t about how bad it feels-it’s about what it does to the person’s life. Confusing intensity with outcome is the most common mistake in safety reporting, and it’s costing time, money, and focus.

What Makes an Adverse Event ‘Serious’?

An adverse event is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug or device being tested. But only a small fraction of these are classified as serious. The definition isn’t vague-it’s legal. According to the FDA and ICH E2A guidelines, an event is serious if it meets any one of these six criteria:

- It caused death

- It was life-threatening (meaning the patient was at immediate risk of dying)

- It required hospitalization or extended an existing hospital stay

- It led to permanent disability or significant incapacity

- It caused a birth defect or congenital anomaly

- It required medical or surgical intervention to prevent any of the above

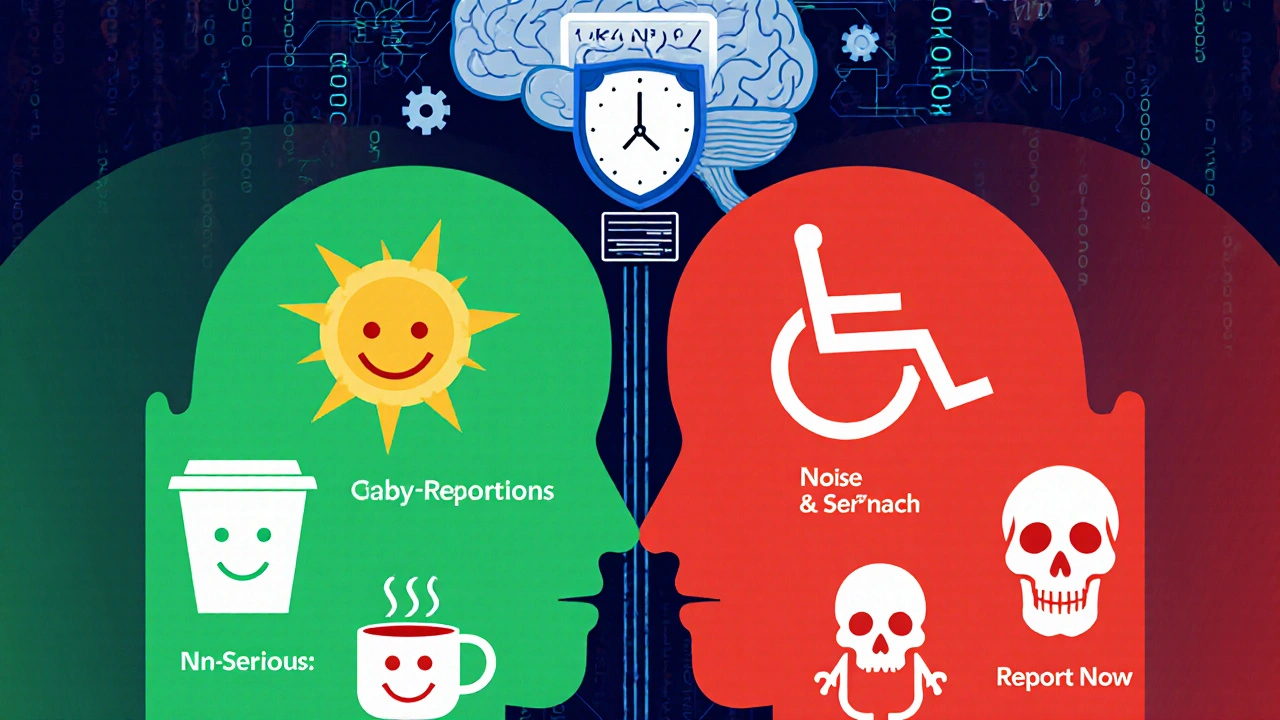

That’s it. No other conditions count. A migraine that knocks someone out for a day? Not serious. A broken rib from a fall? Only serious if it caused lung collapse or needed surgery. A rash that itches? Not serious-even if it’s severe in intensity. Severity (mild, moderate, severe) describes how strong the symptom is. Seriousness describes the outcome. They’re not the same thing.

Dr. Robert Temple, former FDA deputy director, called mixing these up ‘one of the most persistent errors’ in clinical trials. In 2019, nearly 37% of events reported as serious to IRBs didn’t actually meet the criteria. That’s not just noise-it’s a system overload.

When Do You Have to Report a Serious Event?

Time matters. If an investigator learns about a serious adverse event, they must tell the sponsor within 24 hours. That’s non-negotiable. It doesn’t matter if the event seems unrelated to the drug. It doesn’t matter if the patient had other health problems. If it meets one of the six criteria, report it fast.

The sponsor then has to notify the FDA:

- Within 7 days for life-threatening events

- Within 15 days for all other serious events

And if the event is unexpected-meaning it wasn’t listed in the study protocol as a possible risk-it’s reported even faster. This is how regulators catch hidden dangers early.

For Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), serious events must be reported within 7 days. Non-serious events? They’re usually logged in routine reports-monthly or quarterly-and only shared with the IRB if the protocol says so. Some sites don’t report mild events to the IRB at all.

What About Non-Serious Events?

Non-serious adverse events are everything else. A headache that goes away with ibuprofen? A temporary nausea after taking the pill? A bruise from an IV? These are tracked, documented, and analyzed-but not rushed.

They go into Case Report Forms (CRFs). They’re counted in safety summaries. They help build the full picture of how the product behaves over time. But they don’t trigger emergency calls, urgent meetings, or regulatory alerts.

The NIH’s 2018 guidelines break it down simply:

- Mild: Symptoms are noticeable but don’t interfere with daily life. No treatment needed.

- Moderate: Symptoms are uncomfortable enough to require medical attention-but not hospitalization or lasting harm.

- Severe: Intense symptoms, but still not meeting the six seriousness criteria.

Severe ≠ Serious. A patient might have a severe cough that keeps them awake all night-but if they don’t end up in the hospital, it’s not a serious event. Reporting it as one wastes time and distracts from real risks.

Why This Distinction Matters

Imagine a hospital emergency room flooded with reports of ‘serious’ events that are just bad colds. The team reviewing life-threatening reactions might miss the one real danger because they’re buried under 200 false alarms.

The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative has processed over 14.7 million adverse event reports since 2008. Only 18.3% of them met seriousness criteria. That means more than 80% were noise. In 2020, nearly 29% of expedited reports submitted to European regulators didn’t meet the seriousness standard. The same pattern shows up in U.S. research sites: 42% of reports needed clarification. One cancer research network spent nearly 19 full-time hours every week fixing misclassified events.

This isn’t just inefficient-it’s dangerous. When safety teams are overwhelmed, signals get lost. And when a real threat emerges, the system might not be ready to respond.

How to Get It Right

Training is the first line of defense. ICH E6(R2) requires all study staff to be trained on seriousness criteria before starting a trial. Top research institutions now require annual refresher courses. 98.7% of the top 50 sites do it.

Use a decision tree. The NIH recommends asking four simple questions:

- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or significant incapacity?

If the answer to any of these is yes-it’s serious. Report it now. If all answers are no, it’s non-serious. Log it, track it, but don’t panic.

Use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) to grade severity, but keep seriousness separate. Most sponsors now use both systems together. The FDA’s MedWatch Form 3500A includes checkboxes for each seriousness criterion-use them.

What’s Changing in 2025?

Regulators know the system is clogged. In May 2023, the FDA proposed new guidance to standardize seriousness definitions across disease areas. They’re also testing AI tools to automatically sort reports. Early results show AI correctly classifies seriousness in 89.7% of cases-better than humans, who manage only 76.3%.

But AI isn’t replacing people. It’s helping. Human review is still required for final decisions. The goal isn’t automation-it’s clarity.

The EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation, fully in place since 2022, has already cut cross-border reporting confusion by 35%. And by 2025, the ICH’s E2B(R4) system will make electronic reporting consistent worldwide.

Even small changes matter. In 2023, the NIH clarified that emergency room visits alone don’t make an event serious-unless they meet another criterion. That single update cut misreporting in NIH-funded studies by 22%.

What Happens If You Report Wrong?

Under-reporting serious events is a safety risk. Over-reporting non-serious ones is a system risk. Both hurt.

Regulators can delay approvals if safety data looks messy. IRBs may suspend trials for non-compliance. Sponsors face audits, fines, and reputational damage. Research coordinators burn out from endless paperwork.

One site in California reported that misclassified reports took an average of 9.7 extra business days to process. That’s nearly two weeks of delay per incident. Multiply that across hundreds of trials-and you see why this isn’t just a paperwork issue. It’s a patient safety issue.

Bottom Line

Don’t report based on how bad it feels. Report based on what happened.

If a patient dies, is hospitalized, or is permanently harmed-report it immediately. If they get a headache, nausea, or a rash that fades in a few days-log it, but don’t rush. The system only works when the signal isn’t drowned out by noise.

Training, tools, and clear rules are available. Use them. Your job isn’t to report everything. It’s to report the right things-on time.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

No, not by itself. A severe headache is intense, but unless it leads to hospitalization, brain injury, or other outcome-based criteria, it’s not serious. Many patients in trials report severe headaches that resolve with rest or medication. These are logged as non-serious events. Only if the headache causes loss of consciousness, stroke-like symptoms, or requires emergency intervention does it become serious.

Do I need to report an adverse event if it’s not related to the drug?

Yes. Causality doesn’t matter for reporting serious adverse events. If a patient has a heart attack while on a trial drug-even if the drug is unrelated-you still report it as a serious event. The goal is to capture any major medical event that happens during the trial, regardless of cause. The sponsor will later assess whether it’s possibly linked to the product.

Can a non-serious event become serious later?

Yes. An event that starts as non-serious can evolve. For example, a mild skin rash might lead to a severe infection requiring hospitalization. If that happens, you must update the report to reflect the new seriousness status. Always monitor ongoing events and reclassify them if new information meets the six seriousness criteria.

What if I’m not sure whether an event is serious?

When in doubt, report it as serious and mark it as ‘uncertain.’ It’s better to over-report initially than to miss a real safety signal. The sponsor’s safety team will review it and downgrade it if needed. Many institutions have a safety officer or pharmacovigilance team to consult before finalizing reports. Don’t guess-ask.

Are psychiatric symptoms like severe anxiety considered serious?

Only if they meet the outcome criteria. Severe anxiety alone is not serious. But if the anxiety leads to a suicide attempt, hospitalization for psychiatric care, or permanent psychological disability, then it becomes serious. Many clinical research coordinators get confused here because psychiatric symptoms can feel intense. Always focus on the outcome, not the intensity.

Do I need to report adverse events for healthy volunteers?

Yes. Healthy volunteers are still participants in the trial. Any adverse event they experience-whether mild or serious-must be documented and reported according to the same rules. In fact, because they don’t have underlying conditions, adverse events in healthy volunteers can be clearer signals of drug effects.

What happens if I forget to report a serious event on time?

Delays in reporting serious events can trigger regulatory scrutiny, audit findings, or even trial suspension. Sponsors are required to track reporting timelines closely. If a report is late, you’ll need to document why and how it will be corrected. Repeated delays can lead to loss of trial authorization or penalties. Always set reminders and follow your site’s SOPs.

12 Comments

Kartik Singhal-21 November 2025

Ugh. Another 'follow the rules' lecture. 🙄 Meanwhile, the FDA's AI tool that 'correctly classifies 89.7% of cases'? Yeah, right. That's the same AI that missed the 37% of misreported events last year. Someone's getting paid to pretend this system works. #PharmaLies

Chris Vere-22 November 2025

The distinction between severity and seriousness is fundamental yet consistently overlooked. It reflects a broader failure in clinical culture to prioritize outcomes over sensations. The human tendency to equate discomfort with danger is deeply rooted and requires deliberate unlearning. This is not merely procedural-it is epistemological.

Pravin Manani-23 November 2025

Let’s not forget the CTCAE v5.0 grading framework here. Severity (Grade 1-5) is purely symptom-based: Grade 3 = severe but not life-threatening. Seriousness is binary: yes/no based on the six ICH E2A criteria. Mixing them is like confusing a 10/10 pain score with a myocardial infarction. If your site doesn’t have a decision tree on the wall, you’re not compliant. Period.

Mark Kahn-25 November 2025

This is such a helpful breakdown! Seriously, so many new coordinators panic over a rash or headache. Just remember: hospitalization = serious. Otherwise, log it, breathe, and move on. You’re not failing if you don’t report every sneeze. Trust the system, not your anxiety 😊

Daisy L-26 November 2025

So let me get this straight-some guy in a lab coat in Bethesda gets to decide whether my 10/10 migraine is 'serious' or just 'annoying'? And if I don't end up in the ER, it's 'noise'? That’s not science-that’s bureaucratic gaslighting. 🤬 The FDA doesn’t care if you’re incapacitated for three days-they only care if you’re dead or in a bed. What a joke.

Anne Nylander-26 November 2025

i just want to say thank you for this post!! so many of us are overwhelmed and just wanna do right but dont know how. the decision tree is a game changer. i printed it out and taped it to my monitor. seriously. lifesaver. 🙏

Noah Fitzsimmons-27 November 2025

Oh wow. So we're supposed to trust the same people who approved OxyContin? 'Follow the six criteria'-sure. And next you'll tell me the AI doesn't have a bias toward white male patients. Please. You think the FDA gives a damn about a Black woman's chronic pain? They only care when she's dead.

Eliza Oakes-29 November 2025

Wait-so a suicide attempt is only 'serious' if it requires hospitalization? What if they're treated at home? What if they're too poor to get admitted? Are we just supposed to ignore those? This system is designed to protect pharma, not patients. I'm done pretending this is ethical.

Clifford Temple-29 November 2025

This whole 'reporting standards' nonsense is why America’s clinical trials are falling behind. China and India don’t waste time on this bureaucratic nonsense. They get results. We’re drowning in paperwork while they’re curing cancer. Let’s stop pretending we’re the gold standard. We’re not.

Corra Hathaway-29 November 2025

I love how this post says 'don't panic' but then spends 10 paragraphs on how everything will collapse if you misreport a headache 😂. Also, AI classifying events better than humans? Cute. I've seen the training data-it’s 90% white male data from Phase 3 trials. My grandma’s post-op confusion? 'Non-serious.' The AI would’ve missed it. But hey, at least it’s '89.7% accurate.' 🤷♀️

Shawn Sakura- 1 December 2025

Thank you for this. I’ve been in this field for 12 years and I still get confused on the hospitalization criteria-especially when patients are observed overnight for 'precautionary' reasons. The NIH clarification in 2023 was a game-changer. I’ve started using the MedWatch checkboxes religiously. Small changes, big impact. 🙌

Paula Jane Butterfield- 2 December 2025

Just wanted to add: in rural clinics, patients often avoid hospitals due to cost, transportation, or distrust. So a 'non-serious' event might be the only thing they report. We need to be careful not to erase their experience just because it doesn't meet bureaucratic thresholds. Maybe the system needs to evolve-not just the reporting rules, but the way we listen.