The WHO Model Formulary isn’t a formulary at all-not in the way hospitals or insurance plans use the term. It’s a living, evidence-based list of medicines that every country, rich or poor, should have available to save lives. First published in 1977, the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines (EML) is now in its 23rd edition, updated every two years. As of 2023, it includes 591 medicines, covering 369 health conditions, with nearly half of them being generic versions. This isn’t just a suggestion. It’s the closest thing the world has to a universal blueprint for affordable, life-saving drugs.

What Makes a Medicine ‘Essential’?

The WHO doesn’t pick medicines based on popularity or profit. They’re chosen using strict, transparent criteria. To make the list, a medicine must prove three things: it works, it’s safe, and it’s worth the cost. Evidence has to come from high-quality clinical trials-randomized, controlled studies with clear results. The medicine also needs to treat a disease that affects a significant number of people. For example, a drug for a condition that hits fewer than 100 people per 100,000 usually won’t make the cut.

Cost-effectiveness is just as important. If a medicine costs more than three times a country’s annual GDP per person for each extra year of healthy life it gives, it’s unlikely to be included. This keeps the list focused on value, not luxury. The WHO also weighs how easy it is to use. A drug that needs refrigeration, complex monitoring, or specialist training goes on the complementary list-not the core list. The core list is meant for basic clinics, even in remote villages with no power or lab access.

Generics Are the Backbone

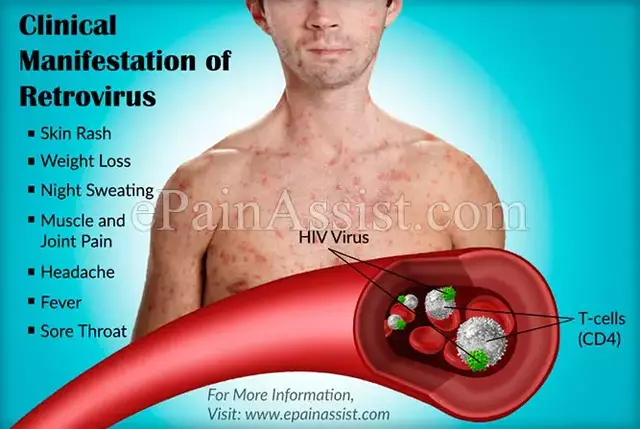

Almost half of the medicines on the 2023 list are generics. That’s not an accident. The WHO knows that without affordable generics, most of the world can’t afford treatment. A generic version of a drug has the same active ingredient, works the same way, and meets the same safety standards as the brand-name version. But it costs a fraction. For example, the price of generic HIV antiretrovirals dropped by 89% between 2008 and 2023-from over $1,000 per patient per year to under $120. That shift turned a once-unreachable treatment into a global standard.

But quality matters. The WHO requires every generic on the list to meet strict standards. Either it’s been prequalified by the WHO itself, or it’s approved by a top-tier regulator like the U.S. FDA, the European EMA, or Japan’s PMDA. These agencies test for bioequivalence-meaning the generic must deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream as the original, within a narrow range. For most drugs, that’s 80% to 125%. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin or lithium-the range is tighter: 90% to 111%. This isn’t just paperwork. It’s what keeps patients safe.

How Countries Use the List

More than 150 countries have built their own national essential medicines lists based on the WHO’s model. In Ghana, adopting the list helped cut out-of-pocket medicine costs by 29% between 2018 and 2022. In India, hospitals using WHO-recommended antibiotic tiers reduced antimicrobial spending by 35%. These aren’t theoretical gains. They’re real savings for families and health systems.

But adoption doesn’t always mean access. In Nigeria, a 2022 survey found that only 41% of essential medicines were consistently available in health facilities. Stockouts averaged 58 days per drug each year-not because the list was wrong, but because supply chains broke down. Delivery systems, storage, training, and funding are just as critical as the list itself. The WHO knows this. That’s why the 2023 update included more guidance on managing supply disruptions and pediatric dosing-areas where many countries struggle.

Global Impact, Local Gaps

The WHO list drives $15.8 billion in annual global procurement. The Global Fund, UNICEF, and Gavi all base their medicine purchases on it. Eighty-five percent of their purchases follow the list. Generic manufacturers have taken notice. Between 2018 and 2023, the number of WHO-prequalified generic products jumped 47%. That’s because companies want to sell to public health programs-and those programs only buy prequalified drugs.

Still, the system has blind spots. Only 12% of new drugs approved between 2018 and 2022 made it onto the 2023 list. Meanwhile, high-income countries added 35-45% of their new drugs to their own formularies. Critics say the WHO moves too slowly. But the process is deliberate. Each update involves 25 independent experts from 18 countries reviewing over 200 applications. They score each drug across four areas: public health need, safety, cost-effectiveness, and feasibility. A drug needs a minimum score of 7.5 out of 10 to be included. That’s not fast-but it’s fair.

Challenges and Criticisms

Not everyone agrees with how the list is made. Some experts worry about industry influence. In 2023, 45% of the evidence used to support new inclusions came from industry-funded trials-up from 28% in 2015. The WHO says it now requires full financial disclosures from all committee members, and compliance was 100% in the last review. Still, concerns linger.

Another issue: substandard medicines. WHO surveillance found that over 10% of essential medicine samples in low- and middle-income countries were fake or poorly made-mostly antibiotics and antimalarials. The list doesn’t solve this problem alone. It needs enforcement: better border controls, stronger regulators, and more testing labs.

And then there’s geography. The world’s generic production is concentrated in just three countries: India, China, and the U.S. During the pandemic, 62% of low-income countries faced shortages because supply chains snapped. The WHO now recognizes this vulnerability. Future updates will include more emphasis on regional manufacturing and diversified sourcing.

What’s Changing in 2024 and Beyond

The WHO isn’t standing still. The 2023 list added seven biosimilars-complex, biologic drugs that mimic expensive treatments like cancer therapies. These were previously out of reach for most countries. Now, they’re included with strict bioequivalence rules: 85% to 115% matching the original. The list also now includes age-appropriate formulations for 42% of medicines, up from 29% in 2019. That means more liquid doses for kids, smaller tablets for the elderly, and better packaging for low-literacy populations.

A new WHO Essential Medicines App, launched in September 2023, has been downloaded over 127,000 times across 158 countries. Pharmacists in rural clinics use it to check dosing, interactions, and availability. It’s a small tool, but it bridges a big gap.

The next big push? Antibiotic stewardship. Draft guidelines released in early 2024 require countries to classify antibiotics into tiers-like those used in hospitals-to prevent overuse and resistance. This is critical. Misuse of antibiotics is fueling a global crisis. The WHO wants the Model List to be part of the solution.

Why This Matters Everywhere

You might think this is only relevant in low-income countries. But it’s not. The WHO Model List sets the global bar for what a medicine should be: effective, safe, and affordable. Even in wealthy nations, drug prices are under pressure. Hospitals in the U.S. and Europe use the list to compare their own formularies and identify where they’re overpaying. Pharmacy benefit managers and insurers sometimes reference it when negotiating prices.

And it’s not just about cost. It’s about equity. When a mother in rural Kenya can get the same antiretroviral as a woman in New York, that’s progress. When a child in Malawi gets the right dose of antibiotics because the tablet is designed for small mouths, that’s dignity.

The WHO Model List doesn’t fix everything. It doesn’t guarantee supply. It doesn’t replace strong health systems. But it gives every country, no matter how poor, a clear, science-backed starting point. It says: you don’t need the latest, flashiest drug. You need the ones that work, that are safe, and that you can actually afford.

That’s not just a list. It’s a promise.

Is the WHO Model Formulary legally binding for countries?

No, the WHO Model List is not legally binding. It’s a technical guide, not a law. But over 150 countries use it as the foundation for their own national essential medicines lists. Many governments adopt it because it’s evidence-based, cost-effective, and aligned with global health goals. While countries can modify it to fit local needs, most stick closely to it because deviating without strong justification can lead to inefficiencies and higher costs.

How often is the WHO Model List updated?

The WHO updates the Model List every two years. The most recent version is the 23rd edition, published in July 2023. The next update is expected in 2025. This biennial cycle allows time for new evidence to emerge, for countries to provide feedback, and for the Expert Committee to thoroughly review applications for new medicines or changes to existing ones.

What’s the difference between the WHO Model List and a hospital formulary?

The WHO Model List is a global standard focused on which medicines should be available to treat priority health conditions. A hospital formulary is a local list of drugs approved for use within that facility, often based on cost, availability, and clinical protocols. Hospital formularies may include more drugs, especially newer or specialty medications, and often include tiered pricing or prior authorization rules. The WHO list doesn’t include those administrative details-it’s about what’s essential, not what’s convenient.

Why are so many generics on the WHO list?

Generics make essential medicines affordable. The WHO prioritizes cost-effectiveness, and generics typically cost 80-95% less than brand-name drugs with the same active ingredient. For countries with limited budgets, using generics is the only way to provide widespread access to treatments for diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, diabetes, and hypertension. The WHO also requires all generics to meet strict quality standards, so affordability doesn’t mean lower safety.

Can a medicine be removed from the WHO Model List?

Yes. Medicines can be removed if new evidence shows they’re less effective, less safe, or no longer cost-effective compared to alternatives. For example, some older antibiotics have been downgraded or removed as resistance has grown. The WHO also removes drugs that are no longer produced or have been replaced by better options. Removal is rare but happens when science moves forward and public health needs change.

How does the WHO ensure generic medicines are safe?

The WHO requires all generic medicines on the Model List to be prequalified or approved by a stringent regulatory authority like the FDA, EMA, or PMDA. Prequalification involves rigorous testing of bioequivalence-ensuring the generic delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream as the original. For narrow therapeutic index drugs, the acceptable range is tighter. The WHO also runs a global surveillance system that tests medicine samples in the field and flags substandard or falsified products.

Write a comment