When your kidneys fail, life doesn’t stop-but it changes. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) means your kidneys have lost about 90% of their ability to filter waste and fluid. Without treatment, toxins build up, fluids swell your body, and your heart struggles to keep up. The choices are clear: dialysis, transplant, or death. But between those options lies a world of trade-offs that affect how you live, not just how long you live.

What Exactly Is End-Stage Renal Disease?

ESRD isn’t just advanced kidney disease-it’s the point where your kidneys can no longer sustain life on their own. Doctors measure this with your glomerular filtration rate (GFR). When it drops below 15 mL/min/1.73 m², you’re in ESRD. That’s not a slow decline; it’s a system failure. About 44% of cases come from uncontrolled diabetes. Another 28% stem from high blood pressure. The rest? Autoimmune diseases like lupus, inherited conditions like polycystic kidney disease, or long-term damage from drugs or toxins.

In the U.S., nearly 800,000 people live with ESRD. Most are on dialysis. Fewer than a third have a functioning transplant. And every month, 3,000 more people join the waiting list for a kidney. The system is overwhelmed. The need is growing. But the solution isn’t just more machines-it’s better access to transplants.

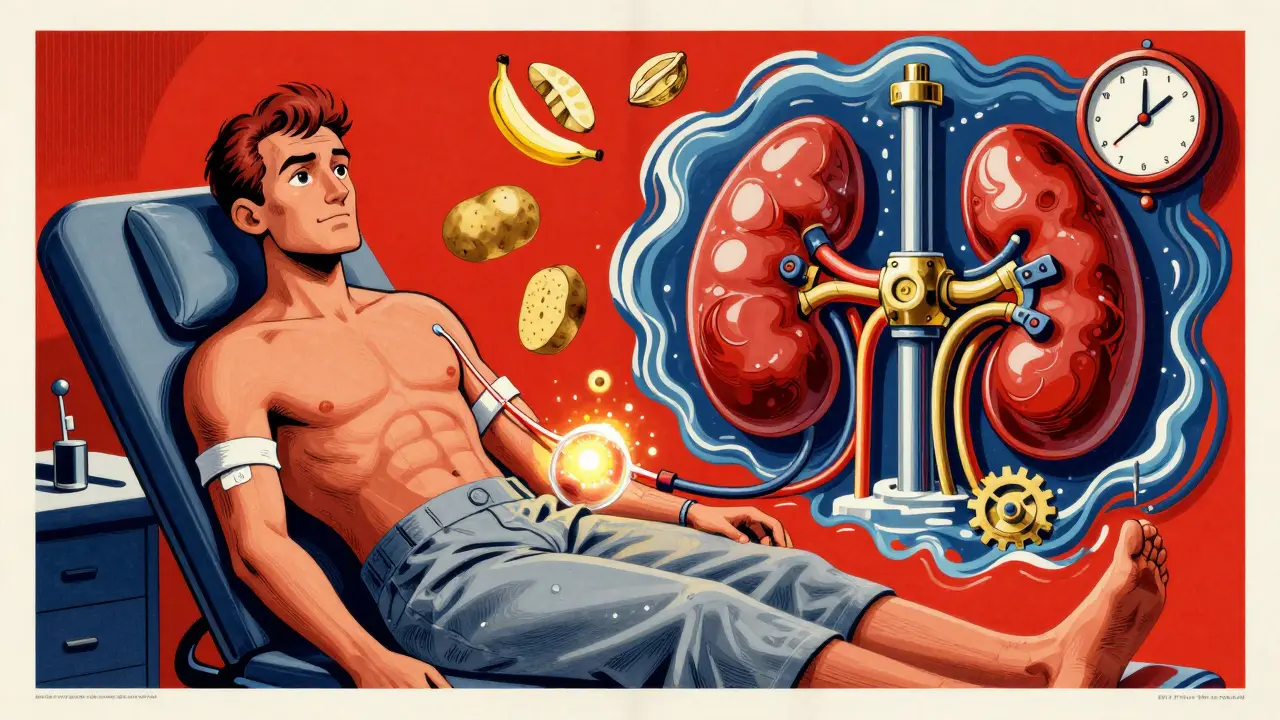

Dialysis: Life Support, Not a Cure

Dialysis keeps you alive, but it doesn’t restore your kidneys. It’s a mechanical replacement. There are two main types: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

Hemodialysis means sitting in a clinic three times a week for 3 to 4 hours while a machine filters your blood. Blood flows out through a fistula-a surgically created connection between an artery and vein in your arm-and back in clean. It’s precise: blood flow rates of 300-500 mL/min, dialysate at 500-800 mL/min. The goal? A Kt/V score of at least 1.4 per session. That’s the measure of how well waste is removed.

Peritoneal dialysis uses your own belly lining as a filter. You fill your abdomen with fluid, let it sit, then drain it out. This can be done manually four times a day (CAPD) or overnight with a machine (APD). It’s more flexible, but it’s also constant. You’re tethered to bags and sterile routines. No travel is simple. No spontaneous meals are safe.

Both types demand strict control. Phosphate must stay between 3.5 and 5.5 mg/dL. Calcium below 9.5 mg/dL. Parathyroid hormone levels must be tightly managed. You’ll need vitamin D analogs, phosphate binders, and blood pressure meds. And even then, you’ll feel tired. Your appetite fades. Your skin itches. Your bones weaken. Your life becomes a cycle of treatments, lab visits, and restrictions.

Kidney Transplant: The Best Option, If You Can Get It

Transplant isn’t just better-it’s dramatically better. A 2021 study found transplant recipients scored 28.7 points higher on quality-of-life surveys than dialysis patients. That’s not a small difference. That’s the gap between living and merely surviving.

Transplant recipients have a 68% lower risk of death than those on dialysis. Five-year survival? 83% for transplant patients. For dialysis? Just 35%. Hospital stays drop by half. Dietary rules loosen. You can eat what you want, travel, work, sleep through the night.

Living donor transplants have the best outcomes: 95.5% survive one year, 86% still have a working kidney after five years. Deceased donor kidneys do almost as well-93.7% at one year, 78.5% at five. But here’s the catch: you have to get one.

There are over 90,000 people on the kidney waiting list in the U.S. Only about 27,000 transplants happen each year. That means you might wait four years. And only 5% of people who start dialysis are even referred for transplant evaluation before they need it. That’s a systemic failure.

Doctors should refer you for transplant evaluation when your GFR drops below 30 mL/min/1.73 m². That’s years before dialysis. But most don’t. Why? Lack of awareness. Fear of surgery. Misconceptions about age or health. And yes-racial bias. African American patients are less likely to be referred, even with the same medical need. Programs like RaDIANT have shown that with education and outreach, referrals can jump by 40%.

The Hidden Cost of Transplant: Lifelong Medication

Yes, transplant is better. But it’s not free. Not physically, not financially.

You’ll take immunosuppressants for the rest of your life. These drugs stop your body from rejecting the new kidney. But they also weaken your immune system. You’re more likely to get infections. You might develop high blood pressure, diabetes, or even certain cancers. The cost? $1,500 to $2,500 a month for meds alone. That’s $18,000 to $30,000 a year.

Medicare covers ESRD treatment starting in the fourth month of dialysis. After a transplant, coverage lasts 36 months. After that? You need private insurance or Medicaid. Many people lose coverage. Many lose their kidney.

And yet, over time, transplant is cheaper than dialysis. Dialysis costs Medicare about $90,000 a year per person. Transplant? Around $35,000 in the first year, then $15,000-$20,000 after that. But that savings doesn’t always reach the patient.

Quality of Life: More Than Survival

Let’s talk about what really matters: your days.

Dialysis patients spend 12 to 16 hours a week in treatment-not counting travel, prep, and recovery. That’s like a part-time job you didn’t sign up for. You can’t just take a weekend trip. You can’t eat a banana, a potato, or a handful of nuts without checking phosphate levels. Your energy is low. Your sleep is broken. Your mood dips.

Transplant patients? They wake up without alarms. They eat meals without restrictions. They sleep through the night. They go to work. They play with their kids. They travel. Their KDQOL-36 score averages 82.4 out of 100. Dialysis? 53.7. That’s not just a number. That’s joy. That’s freedom.

Even peritoneal dialysis, which offers more flexibility than in-center hemodialysis, still scores only 67.2. It’s better than clinic dialysis-but not close to transplant.

Who Can Get a Transplant?

Not everyone qualifies. Age alone doesn’t disqualify you-but serious heart disease, active cancer in the last 2-5 years, uncontrolled mental illness, or ongoing substance abuse do. Some centers won’t transplant people over 75 unless they’re exceptionally healthy.

But here’s the truth: most people who think they’re too old or too sick aren’t. A 70-year-old with controlled diabetes and no heart problems is often a better candidate than a 50-year-old with uncontrolled hypertension and obesity. Evaluation is key. Don’t assume you’re not eligible. Get assessed.

What Can You Do Now?

If you have advanced kidney disease:

- Ask for a transplant evaluation now. Don’t wait until you’re on dialysis. Get referred when your GFR is below 30.

- Find a living donor. Family, friends, even strangers can donate. One kidney is all it takes. Living donor transplants have the best outcomes.

- Get a fistula placed. If you’ll need dialysis, have an arteriovenous fistula created 6-12 months before you start. It lasts longer and has fewer complications than catheters.

- Know your rights. Medicare covers ESRD. You’re entitled to transplant evaluation. If your doctor won’t refer you, ask why. Get a second opinion.

- Join a support group. You’re not alone. Connect with others who’ve walked this path. They know the system. They know the pain. And they know the hope.

The Future: More Transplants, Better Access

Things are changing. Living donor transplants have risen 18% since 2018. Deceased donor transplants are up 14%. The 21st Century Cures Act has expanded the donor pool by letting doctors use kidneys from older or higher-risk donors. That’s 15% more kidneys available since 2017.

New payment models like the Kidney Care Choices Model are pushing providers to refer patients earlier. The NIH has invested $157 million through 2026 to study personalized kidney treatments. That means someday, we might slow or even reverse kidney damage before it reaches ESRD.

But progress is slow. The waiting list grows faster than transplants. Disparities persist. Access remains unequal. The system still favors those who know how to ask.

So if you or someone you love is facing ESRD: speak up. Push for transplant. Demand evaluation. Fight for your life-not just your survival.

Can you live a normal life on dialysis?

You can live on dialysis, but "normal" is relative. Most people feel tired, have dietary restrictions, and need to schedule their lives around treatments. Travel is harder. Social activities are limited. You can work, raise a family, and enjoy moments-but it’s a constant balancing act. Many describe it as living in slow motion.

Is a kidney transplant worth the risk?

For most people, yes. Transplant recipients live longer, have fewer hospital visits, and report far better quality of life. The biggest risk is rejection or infection from immunosuppressants. But 90% of living donor transplants still work after five years. The trade-off-lifelong meds for freedom-is worth it for the vast majority.

Why are transplant wait times so long?

There aren’t enough kidneys. About 90,000 people are waiting, but only 27,000 transplants happen each year. Most kidneys come from deceased donors, and not everyone is a match. Living donors can speed this up dramatically-yet only about 20% of transplants come from living donors. More awareness and fewer barriers could cut wait times in half.

Can older adults get a kidney transplant?

Absolutely. Age alone doesn’t disqualify you. Many transplant centers now evaluate people in their 70s and even 80s. What matters more is overall health-heart function, lung capacity, absence of active cancer, and mental readiness. A healthy 75-year-old often has better outcomes than a frail 50-year-old.

Does Medicare cover transplant medications after 36 months?

No. Medicare stops covering immunosuppressants 36 months after a successful transplant. After that, you need private insurance, Medicaid, or a patient assistance program. Many people lose coverage and risk losing their transplant. It’s a major gap in the system. Always plan ahead-talk to your social worker about long-term medication funding.

What’s the difference between living and deceased donor transplants?

Living donor transplants have higher success rates and shorter wait times. A kidney from a living donor usually starts working immediately. Deceased donor kidneys may take days or weeks to function fully. One-year survival is 95.5% for living donor kidneys versus 93.7% for deceased. Five-year survival is 86% vs. 78.5%. Living donors also reduce the overall waiting list.

14 Comments

Jennifer Littler-11 January 2026

Dialysis is brutal. I’ve seen my mom go through it for 5 years-3x a week, 4 hours each, and still she’d come home shaking, nauseous, exhausted. The phosphate binders? She had to swallow 12 pills a day just to eat a slice of toast. No one talks about how it steals your dignity. You’re not living-you’re just not dead yet.

Vincent Clarizio-12 January 2026

Let’s be real-this whole system is a grotesque parody of medical ethics. We’ve got a population that’s been systematically neglected by Big Pharma and Medicare bureaucracy, and now we’re pretending that a 36-month medication cliff is somehow ‘reasonable.’ The fact that we’re still debating whether a 75-year-old deserves a kidney while CEOs get 17th-generation CRISPR tweaks for their gout is the moral equivalent of letting a fire burn because the hose is ‘too expensive.’ Transplant isn’t a luxury-it’s a human right. And if your doctor doesn’t get that, they’re not a healer-they’re a gatekeeper for a broken machine.

Sam Davies-14 January 2026

Oh wow, another ‘transplant is better’ manifesto. How original. Did you get this from a kidney foundation pamphlet or just Google ‘kidney survival stats’ and call it a day? The real issue isn’t transplants-it’s that we’ve turned chronic illness into a moral test. If you’re poor, you’re lazy. If you’re Black, you’re ‘non-compliant.’ If you’re old, you’re ‘not worth it.’ Meanwhile, the system just keeps churning out dialysis machines like they’re vending machines for human suffering. Bravo.

Christian Basel-14 January 2026

Kt/V 1.4? That’s the bare minimum. Most centers hit 1.6–1.8 for optimal clearance. Also, PTH should be 150–300 pg/mL, not just ‘tightly managed.’ And don’t get me started on the calcium-phosphate product-should be under 55, not 50. This post is full of oversimplifications. If you’re gonna write about ESRD, at least know the numbers.

Alex Smith-16 January 2026

Yeah, transplant is better-but why do we act like it’s some magical cure? You still need to take immunosuppressants, still get infections, still watch your diet (just less strictly). And the cost? I know a guy who lost his transplant because his insurance dropped him after 36 months. He’s back on dialysis. The system doesn’t care if you survive-it cares if you’re profitable. So yeah, transplant’s great… if you’ve got the right paperwork and the right race.

Michael Patterson-16 January 2026

Transplant is the only way to live but most people dont even know they can get eval before dialysis and doctors are too lazy to refer them and then they wonder why people die on lists. Also living donors are the real heroes. I wish more people would just step up instead of waiting for someone to die for them to get a kidney. Its not that hard to get tested.

Matthew Miller-17 January 2026

Stop romanticizing transplant. It’s not freedom-it’s a new kind of prison with a different lock. You trade dialysis for lifelong immunosuppression, cancer risk, and financial ruin. And don’t tell me ‘90% survive five years’-that’s not a victory, that’s a statistic that ignores the 10% who die screaming from rejection or infection. This post is a sales pitch for the transplant industrial complex. Wake up.

Madhav Malhotra-19 January 2026

In India, dialysis costs $50–80 per session. Transplant? Around $15,000 total if you go to a good private hospital. But most people can’t afford even that. We have no public healthcare for ESRD. So families sell land, borrow from loan sharks, or just give up. I’ve seen it too many times. The real tragedy isn’t just the medical gap-it’s the economic one. No one talks about that.

Priya Patel-19 January 2026

I’m a nurse who works in nephrology. I’ve held hands through 1000+ dialysis sessions. I’ve cried with families waiting for transplants. I’ve watched people lose their kidneys after 36 months because they lost insurance. Please-don’t just read this and feel sad. Do something. Talk to your doctor. Ask about living donation. Share this. We’re not just numbers. We’re people. 💕

Jason Shriner-21 January 2026

Transplant = freedom? More like ‘freedom with a side of lifelong medication and existential dread.’ I mean, congrats, you got a new kidney-but now you’re basically a human pharmacy. And if you sneeze too hard, you might get sepsis. Great trade. 🤡

Alfred Schmidt-23 January 2026

Why is no one talking about the fact that Medicare covers dialysis but ABANDONS transplant patients after 36 months?! That’s not policy-that’s cruelty! I’ve seen people lose their kidneys because they couldn’t afford cyclosporine. And you want to call this a healthcare system? It’s a death sentence with a spreadsheet. Someone needs to sue the damn government.

Sean Feng-25 January 2026

Dialysis is a death sentence. Transplant is a gamble. Either way you lose. The system doesn’t care. Stop pretending it does.

Priscilla Kraft-26 January 2026

My brother got a living donor kidney from his sister last year. He’s back to coaching soccer, traveling, eating pizza without guilt. It’s not perfect-he takes meds, has checkups-but he’s alive, really alive. If you’re reading this and you’re healthy? Consider getting tested to donate. One kidney. One life. No big deal. 🙏❤️

Roshan Joy-28 January 2026

As someone from India who’s seen both sides-dialysis in a rural clinic and transplant in a private hospital-I can say this: the real barrier isn’t medical. It’s access. In the US, you have Medicare. In India, you have hope. And sometimes, that’s not enough. But I’ve met families who pooled money for years to get one transplant. They didn’t wait for permission. They just did it. If you’re reading this and you’re scared to ask for a referral? Don’t be. Ask. Push. Fight. Your life matters more than their bureaucracy.