Every day, pharmacists dispense over 4 billion prescriptions in the U.S. - and about 75% of those are generic drugs. These medications save patients and the healthcare system billions annually. But when a generic drug doesn’t work the same way as the brand-name version - when a patient suddenly has seizures after switching to a cheaper pill, or when a chronic condition worsens despite perfect adherence - someone has to speak up. That someone is often the pharmacist.

What Exactly Is a Generic Drug Problem?

Not all problems with generics are about side effects. The real danger often lies in therapeutic inequivalence. This means the generic drug meets FDA bioequivalence standards in lab tests but fails in real life. Patients report different effectiveness, unexpected side effects, or sudden loss of symptom control after switching from brand to generic - or even between different generic manufacturers.

The FDA defines therapeutic inequivalence as a clinical response that differs from what’s expected based on the reference drug. For example: a patient on a generic seizure medication starts having breakthrough seizures. Or someone on a generic blood thinner sees their INR levels spike without any dose change. These aren’t random. They’re signals.

These aren’t rare. Between 2015 and 2022, reports of generic drug problems to the FDA jumped 131%. And in 2022 alone, the FDA’s Office of Generic Drugs received 1,842 reports specifically about therapeutic inequivalence. Of those, 387 came from pharmacists - up from 354 the year before. That’s progress, but it’s still only 21% of total reports from frontline providers who see these issues daily.

Are Pharmacists Legally Required to Report?

No. Federal law does not force pharmacists to report adverse events. The FDA encourages reporting through MedWatch, but it’s voluntary for healthcare professionals. That’s a critical gap. Unlike manufacturers - who are legally required to report serious adverse events - pharmacists operate in a gray zone. They’re trusted with the final handoff of medication, yet they have no legal obligation to report when something goes wrong.

But here’s the catch: while federal law doesn’t mandate it, state laws do. Four states - California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York - require pharmacists to report serious adverse events. The California State Board of Pharmacy explicitly states pharmacists must “maintain a system for identifying, documenting, and reporting adverse drug reactions and therapeutic failures.” Other states are moving in that direction. In 2022, 28 states had some form of reporting expectation written into pharmacy board regulations.

So while the federal system is voluntary, professional responsibility isn’t. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) calls adverse event reporting a “fundamental professional responsibility.” The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) flags pharmacies with low reporting rates as having “significant safety concerns.” If you’re a pharmacist, ignoring these signals isn’t just negligent - it’s a breach of your ethical duty.

Why Pharmacists Are the Best Eyes on the Ground

Pharmacists are the only healthcare providers who see the same patient across multiple refills. They know when a patient switches from one generic brand to another. They hear complaints during counseling. They notice when a patient says, “This new pill makes me dizzy,” or “I’ve been taking this for years, but now it’s not working.”

Doctors prescribe. Nurses administer. Patients take. But pharmacists track. They see patterns. One patient with a bad reaction? Maybe coincidence. Three patients on the same generic version of levothyroxine reporting fatigue and weight gain? That’s a signal.

University of North Carolina researchers found that 63% of the 478 generic drugs flagged for potential safety issues in 2022 were first identified by pharmacists noticing patterns across multiple patients. These aren’t lucky guesses. They’re clinical observations backed by experience.

Dr. Jerry Phillips, former FDA official, put it plainly: “Pharmacist reports of therapeutic inequivalence are particularly valuable because they represent real-world evidence that lab tests missed.”

The Reporting Process: What You Need to Know

Reporting isn’t complicated - but it’s easy to skip if you don’t know what to include. The FDA’s MedWatch Form 3500 (version 4.1, updated January 2023) requires four key elements:

- An identifiable patient (age, gender, initials - no full name needed)

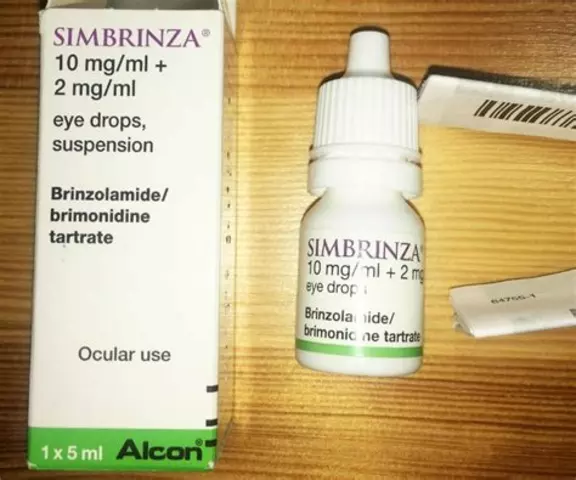

- The suspect drug - including the exact generic manufacturer and National Drug Code (NDC)

- A clear description of the adverse event

- Your contact information as the reporter

Don’t write: “Patient had a bad reaction.” That’s useless. Write: “72-year-old male, switched from Teva levothyroxine 88 mcg to Mylan levothyroxine 88 mcg. Within 10 days, TSH rose from 2.1 to 8.7. Symptoms: fatigue, weight gain 8 lbs, cold intolerance. No other medication changes. Patient returned to Teva brand - TSH normalized in 4 weeks.”

That’s actionable data. The FDA’s system can detect signals from reports like this. And they’ve created a new “generic drug concern” category in MedWatch (version 3.2, April 2023) that lets you specify whether the issue is therapeutic inequivalence, manufacturing quality, or labeling.

For serious events - those that are life-threatening, cause hospitalization, or lead to permanent disability - the FDA expects reports within 15 calendar days. But even non-serious events should be reported if they’re unexpected. Why? Because hidden patterns emerge from small signals.

Why So Few Pharmacists Report - And How to Overcome It

Only 2.3% of all adverse event reports to the FDA between 2018 and 2022 came from pharmacists. Why? Three big barriers:

- Lack of time (68.4% of pharmacists cite this)

- Uncertainty about what counts (52.1%)

- Difficulty identifying which manufacturer made the pill (41.7%)

The manufacturer confusion is real. Because of the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, generic manufacturers must use the same labeling as the brand drug. That means when a patient has a reaction, the pharmacy label doesn’t tell you which company made the pill - unless you check the NDC on the bottle. Many pharmacists don’t routinely record that. And even if they do, patients often refill at different pharmacies, so the manufacturer changes.

Here’s what you can do:

- Always note the NDC and manufacturer name on the prescription file or in your pharmacy software.

- Use the FDA’s free MedWatch training modules - especially Module 4: “Reporting for Healthcare Professionals,” updated January 2023.

- Start a simple log: one spreadsheet with date, patient ID (initials), drug name, manufacturer, NDC, event, and outcome. You don’t need fancy software.

- Report even if you’re unsure. The FDA says: “Reports should be submitted even where the healthcare provider is not certain the product caused the event.”

And don’t wait for a crisis. If you notice a pattern - even just two patients with similar issues on the same generic - report it. The FDA’s Therapeutic Equivalence Working Group has used pharmacist reports to trigger reviews of 147 generic products since 2019. Twelve of those led to direct communications to providers about potential risks.

The Bigger Picture: Liability, Incentives, and Broken Systems

There’s a legal reason why manufacturers don’t report problems as often as they should. In 2011, the Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing that generic manufacturers can’t be sued for failing to update warning labels - because federal law forces them to copy the brand’s label. That decision removed any legal incentive for manufacturers to investigate or report problems with their own products.

What happened next? A 2020 Duke University study found that adverse event reports for generic drugs dropped 17.3% in the three years after the ruling. The system lost a key watchdog.

Now, the burden falls on pharmacists. And it’s unfair. Pharmacists aren’t paid to do this. No reimbursement. No recognition. No time. Yet they’re the ones who see the most data.

The American Pharmacists Association calls adverse event reporting one of the top five “undervalued clinical services.” Only 43.6% of community pharmacists report doing it routinely - even though 89.2% say they feel responsible.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about fixing a system that depends on the people who see the most - but are given the least support.

What Needs to Change

Pharmacists shouldn’t have to fight the system to do the right thing. Here’s what needs to happen:

- States should make reporting mandatory for serious events - like California and New York already have.

- Pharmacy boards should require documentation of adverse event monitoring as part of continuing education.

- Pharmacies should build reporting into workflow - maybe even assign one pharmacist per shift to review and submit reports weekly.

- The FDA should create a simple, one-click reporting tool inside common pharmacy software systems.

- Reimbursement for safety monitoring services should be explored - just like medication therapy management (MTM).

Until then, pharmacists must act. Because if no one reports, the FDA can’t act. And patients keep getting hurt.

Real Impact: When a Report Saved Lives

In 2021, a pharmacist in Ohio noticed three patients on the same generic metoprolol succinate had unusually low heart rates and dizziness. All had switched to a new manufacturer. She reported it. The FDA reviewed the data, checked lab results, and found the generic had a different release profile - slower than expected. It wasn’t bioequivalent in practice. The FDA issued a safety communication. The product was pulled from the market. Patients were switched back. No one died. But they could have.

That pharmacist didn’t get a medal. She didn’t get paid. But she did her job.

Do pharmacists have to report generic drug problems by law?

No, federal law does not require pharmacists to report adverse events or generic drug problems. The FDA encourages reporting through MedWatch, but it’s voluntary for healthcare professionals. However, four states - California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York - have made reporting serious adverse events mandatory for pharmacists. Professional organizations like ASHP and ISMP treat reporting as a core ethical duty, even if not legally required.

What kind of generic drug problems should I report?

Report any situation where a patient has a clinical response different from what’s expected after switching to a generic drug. This includes loss of symptom control, unexpected side effects, or sudden changes in lab values (like INR or TSH). The FDA specifically asks for reports of therapeutic inequivalence - when a generic fails to perform like the brand in real-world use, even if it passed lab tests. Also report manufacturing issues like pills that crumble, unusual taste, or color changes.

How do I find out which manufacturer made the generic drug?

Look at the National Drug Code (NDC) on the prescription label or bottle. The NDC is a 10- or 11-digit number. You can enter it into the FDA’s NDC Directory online to identify the manufacturer. Many pharmacy systems now auto-populate this info. Always record the NDC and manufacturer name in the patient’s file - especially when a patient reports a problem after a switch.

Is it worth reporting if I’m not sure the drug caused the problem?

Yes. The FDA’s 2023 guidance says reports should be submitted even if you’re not certain the drug caused the event. Your suspicion matters. The system relies on patterns - one report might seem insignificant, but five similar reports from different pharmacists can trigger a safety review. Better to report and be wrong than to stay silent and miss a dangerous trend.

Why do so few pharmacists report adverse events?

The main reasons are lack of time (68.4%), uncertainty about what qualifies (52.1%), and difficulty identifying the generic manufacturer (41.7%). Many pharmacists feel overwhelmed and don’t know where to start. Training is available for free through the FDA’s MedWatch portal, and simple tracking tools can help. But the system isn’t designed to make reporting easy - which is why so many skip it, even when they know they should.

Can reporting generic drug problems help me professionally?

Absolutely. Documenting and reporting adverse events is part of providing comprehensive pharmaceutical care. It shows clinical judgment, patient advocacy, and commitment to safety - all qualities that strengthen your professional reputation. Some pharmacy boards now recognize reporting as part of continuing competency. In the long run, it positions you as a leader in medication safety - not just a dispenser.

Next Steps: What You Can Do Today

- Check your pharmacy software - does it capture the NDC and manufacturer name automatically? If not, add a field.

- Review your last 20 generic prescriptions. Did you record the manufacturer? If not, start now.

- Watch for patients who say, “This new pill isn’t working like the last one.” Don’t dismiss it.

- Go to the FDA’s MedWatch Training Portal. Complete Module 4. It takes 20 minutes.

- Submit one report this week. Even if it’s small. The system needs your voice.

Generic drugs are essential. But they’re not perfect. And if no one speaks up, the failures stay hidden - and patients keep paying the price.

Write a comment