Every year, millions of people in the U.S., Europe, and Australia rely on life-saving drugs like insulin, antibiotics, and heart medications. But in 2025, those pills aren’t always on the shelf. Why? Because foreign manufacturing still controls nearly 80% of the active ingredients in prescription drugs - and when that system stumbles, patients pay the price.

How Did We Get Here?

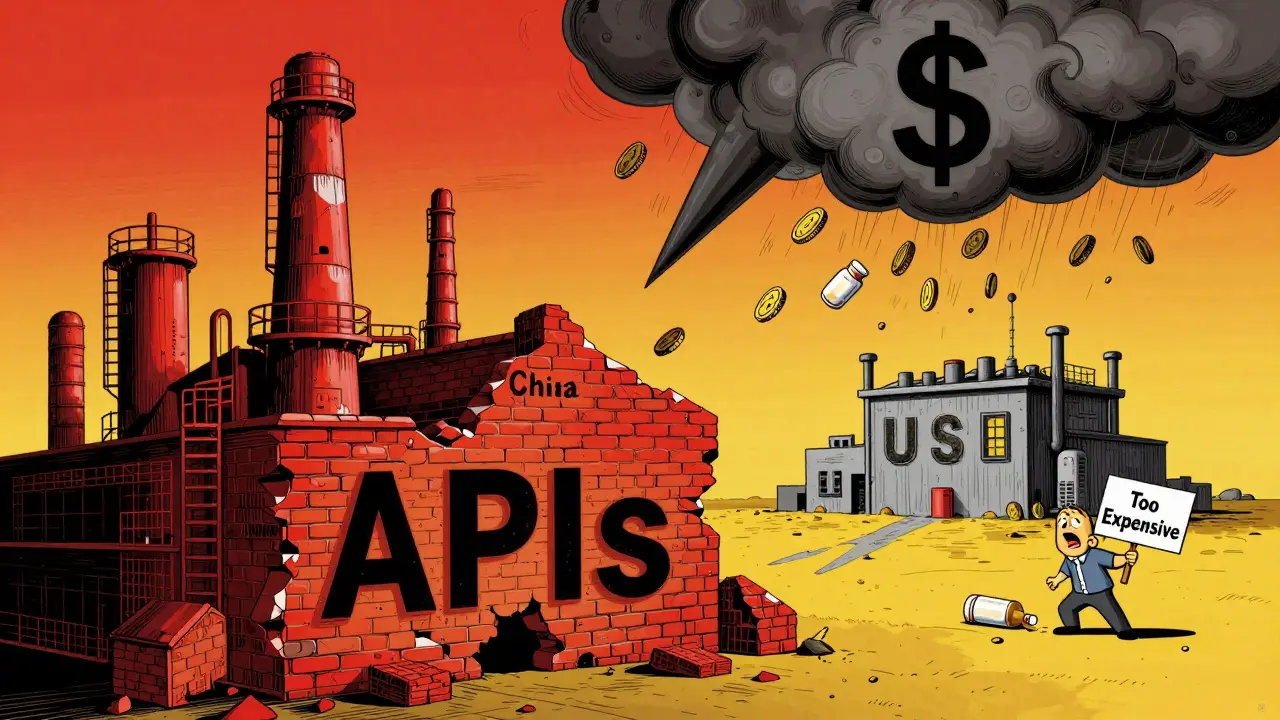

It wasn’t always this way. Decades ago, most medicines were made close to home. But starting in the 1990s, drug companies began chasing lower costs. China and India became the go-to sources for raw materials and finished pills. Why? Because labor was cheaper, regulations were looser, and scale was massive. By 2025, China produces over 40% of the world’s active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), and India handles another 30%. Together, they supply nearly 90% of the generic drugs used in Western countries. This shift saved billions - but it also made the system fragile. A single port closure in Shanghai, a factory shutdown in Gujarat, or a sudden trade ban can ripple across continents. In 2024, when Chinese ports shut down for 45 days due to labor strikes, over 200 drug shortages hit U.S. hospitals. Some lasted more than six months.The Real Cost of Cheap Medicine

You might think: “If it’s cheaper, why does it matter?” But the hidden costs are staggering. - Lead times for drug ingredients from Asia to North America have jumped 50% since 2019. What used to take 30 days now takes 45-60. - Inventory buffers have grown by 15% as companies try to stockpile, but many small pharmacies can’t afford to hold extra stock. - Tariffs added in 2024 and 2025 have raised the cost of key APIs by 200-300% for some drugs. That doesn’t mean prices at the pharmacy went up - it means manufacturers cut back on production. In 2025, the U.S. saw 320 drug shortages - the highest number since 2012. Over half were for antibiotics, cancer treatments, and anesthetics. Hospitals rationed doses. Patients waited weeks for replacements. Some skipped doses entirely.Why Isn’t This Fixed Yet?

You’d think companies would have learned from the pandemic. But changing a global supply chain isn’t like flipping a switch. Building a single API plant in the U.S. or Europe costs $200 million to $500 million. It takes 3-5 years. And even then, the labor and energy costs are 4-5 times higher than in China. That’s why most companies still rely on Asia - they can’t afford to switch. Some tried. A major U.S. insulin maker invested $300 million to bring production back to Ohio in 2023. But after two years, they were still struggling with quality control. Their output was 30% lower than their Asian partner’s. They ended up keeping both. Others turned to nearshoring. Mexico became a popular middle ground. Transportation costs dropped 35%, and lead times shrank to under 10 days. One Fortune 500 medical device maker cut its drug delivery delays by 80% after shifting 40% of production to Monterrey. But labor there still costs 20% more than in India - and skilled workers are hard to find.

The Digital Fix: AI, IoT, and Blockchain

Technology is helping - but not fast enough. - AI-driven forecasting is now used by 68% of major pharma firms, up from 22% in 2020. It helps predict shortages before they happen - but only if the data is accurate. And much of that data still comes from overseas suppliers who don’t always share it in real time. - IoT sensors on shipping containers now track temperature, humidity, and location. That’s critical for drugs that spoil easily. But only 30% of suppliers in India and China use them. - Blockchain is being tested to verify the origin of APIs. One pilot in Germany cut counterfeit drug claims by 65%. But adoption is slow. Many suppliers see it as an extra cost - not a safety net. The truth? Digital tools help, but they don’t solve the core problem: we’re still too dependent on a few countries for the building blocks of medicine.Who’s Most Affected?

It’s not just hospitals. It’s you. - Elderly patients on blood thinners can’t get their prescriptions refilled. - Parents of children with asthma can’t find their inhalers. - Cancer patients wait for chemotherapy drugs that are delayed by customs delays in Singapore or factory inspections in Bengaluru. Small pharmacies feel it worst. They don’t have the buying power to stockpile. When a drug disappears, they can’t just order more - they have to tell patients to go elsewhere. Or worse - go without. A 2025 survey by the National Foreign Trade Council found that 56% of U.S. pharmacies had to reduce or delay drug offerings because of supply issues. In rural areas, that number jumped to 71%.What’s Changing in 2025?

There’s a slow shift happening. - Multi-shoring is becoming standard. Instead of relying on one country, companies are now sourcing from three or four. One major U.S. drugmaker now gets its antibiotics from India, Mexico, Poland, and Vietnam. It cost more upfront - but now they’ve cut disruption days by 65%. - Government incentives are starting. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act now includes $1.2 billion in grants for domestic API production. The EU launched a similar fund. Australia is quietly investing in local sterile injectable manufacturing. - Regulations are tightening. The FDA now requires more frequent inspections of foreign facilities. In 2024, they shut down 17 plants in India and China for quality violations - up from 5 in 2020. But progress is uneven. Only 40% of Asian-based manufacturers have fully adopted multi-shoring. Most still bet everything on China.

The Hard Truth

There’s no magic solution. You can’t just bring all drug manufacturing home. It’s too expensive. Too slow. Too complex. But you can reduce the risk. And you should. The goal isn’t to eliminate foreign manufacturing. It’s to stop depending on it. That means:- Investing in diversified suppliers - not just cheaper ones.

- Building buffer stock for critical drugs - even if it costs more.

- Supporting local production for essential medicines - antibiotics, insulin, epinephrine.

- Pushing for transparency - knowing where your drugs come from, not just how much they cost.

What You Can Do

You don’t control global supply chains. But you can influence them. - Ask your pharmacist: “Where is this drug made?” If they don’t know, ask why. - Support policies that fund domestic pharmaceutical production. - Don’t assume cheaper is better. A drug made in a regulated facility with traceable ingredients is worth more than one that’s just cheap. - If you’re on a long-term medication, keep a 30-day backup supply - if your doctor allows it. The next time you pick up a prescription, remember: that little bottle didn’t just appear. It traveled thousands of miles, passed through multiple factories, and survived customs, tariffs, and delays. And if one link breaks - your health might be the one that suffers.Will This Get Better?

Maybe. But not on its own. The OECD predicts global GDP will grow just 2.9% in 2025 - partly because trade barriers are slowing everything down. If countries keep treating drug supply chains like a cost-cutting exercise, shortages will keep happening. The companies that survive? Those that treat supply chains like lifelines - not line items. The patients who survive? Those who demand better.Why are drug shortages still happening in 2025 if companies know about the risks?

Because switching suppliers is expensive and slow. Building a new manufacturing plant takes 3-5 years and costs hundreds of millions. Most companies still rely on low-cost Asian suppliers because they can’t afford to change overnight. Even when they try, quality control and workforce shortages make it harder than expected.

Is it safer to buy drugs made in Australia or the U.S.?

Not necessarily. Where a drug is made doesn’t automatically mean it’s safer. What matters is whether the facility follows strict quality standards like FDA or EMA regulations. Some Indian and Chinese factories meet those standards - others don’t. The key is transparency: know which facility made your drug and whether it’s been inspected recently.

How does nearshoring to Mexico help with drug shortages?

Mexico cuts shipping time from weeks to days - reducing lead times by 30-40% compared to Asia. It’s also politically stable and has strong trade ties with the U.S. Some companies have cut delivery delays by 80% after shifting production there. But labor costs are higher, and skilled workers are still in short supply.

Can AI really prevent drug shortages?

Ai helps predict shortages by analyzing supplier data, weather patterns, and shipping delays. But it only works if the data is accurate and shared in real time. Many foreign suppliers still use outdated systems or refuse to share data, which limits AI’s effectiveness. It’s a tool - not a fix.

What’s being done in Australia to reduce reliance on foreign drug manufacturing?

Australia is quietly investing in local sterile injectable production - things like IV antibiotics and anesthetics. The Therapeutic Goods Administration has started offering grants to local manufacturers who can meet high-volume, high-quality standards. But for most pills and generics, Australia still imports over 85% of its active ingredients - mostly from India and China.

Are generic drugs more vulnerable to shortages than brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs have razor-thin profit margins, so manufacturers cut corners to stay competitive. They often rely on a single supplier for active ingredients. If that supplier has a problem, there’s no backup. Brand-name drugs usually have multiple suppliers and bigger budgets to buffer disruptions.

How long does it take to build a new drug manufacturing plant?

At least 3-5 years. That includes land acquisition, environmental reviews, regulatory approvals, construction, equipment installation, and FDA inspections. Even then, ramping up to full production takes another 12-18 months. That’s why most companies are trying to diversify existing suppliers instead of building new ones.

12 Comments

Donna Packard-15 December 2025

It’s easy to forget that behind every pill is a whole system - people, planes, factories, and paperwork. I just filled my mom’s insulin prescription last week, and the pharmacist said it came from Poland this time. Not China. I didn’t even know that was possible. Small changes add up.

Radhika M-17 December 2025

Hi, I work in pharma in India. Many factories here follow FDA rules, even better than some US ones. But big companies still pick the cheapest, not the best. It’s not our fault. We make good medicine. You just need to ask where it’s from.

Jonathan Morris-17 December 2025

Let’s be real: this isn’t about supply chains. It’s about the deep state letting China control our medicine to weaken American sovereignty. The FDA’s inspections? A theater. The real shutdowns are hidden in classified trade agreements signed under the guise of ‘economic efficiency.’ Wake up.

Martin Spedding-18 December 2025

OMG. I just found out my blood pressure med is from India. Like… the one with the 2024 recall? I’m gonna die. This is a national emergency. Someone call the president. Or a doctor. Or both. I’m scared.

Raven C-20 December 2025

How profoundly regressive it is to reduce the sanctity of pharmaceutical integrity to mere logistical convenience. One cannot, in good conscience, permit the commodification of life-sustaining compounds to be dictated by the lowest bidder - especially when the geopolitical implications are so manifestly destabilizing. The moral bankruptcy of this system is staggering.

Sam Clark-21 December 2025

Thank you for writing this. It’s clear, factual, and doesn’t panic. I’ve been working with rural clinics for 12 years, and the shortages are devastating. The solution isn’t to abandon global trade - it’s to invest in redundancy. Diversify suppliers. Fund local capacity. Track origins. These aren’t radical ideas. They’re basic risk management.

Jessica Salgado-21 December 2025

Wait - so you’re telling me my asthma inhaler traveled from Bengaluru to Los Angeles, sat in a warehouse for 3 weeks, got stuck in customs because of a paperwork glitch, and then ended up on my shelf… and I just assumed it was ‘just medicine’? I’m crying. I didn’t realize how fragile this all is. I’m going to start asking my pharmacist where everything comes from. Right now.

Chris Van Horn-23 December 2025

Of course you're all being naive. This isn't about 'supply chains' - it's about the globalist elite deliberately outsourcing our healthcare to bankrupt the middle class and force us into state-run medicine. The FDA's inspections? A joke. The 'grants' you mention? Just bait to get you to accept nationalization. Wake up. This is Phase 2 of the Great Depopulation Agenda.

Virginia Seitz-23 December 2025

My grandma’s heart med came from Australia last month! 🇦🇺❤️ She said it tasted different - but it worked! I’m so proud of her pharmacy for asking questions. Small wins, y’all. 😊

Peter Ronai-25 December 2025

You think Mexico is the answer? Please. Labor costs are higher, quality control is worse, and half those ‘nearshore’ plants are owned by Chinese investors anyway. You’re not solving anything - you’re just moving the problem 2,000 miles closer to your doorstep. This is performative activism wrapped in logistics.

Steven Lavoie-26 December 2025

I’ve worked in supply chain logistics for 20 years. The real bottleneck isn’t China - it’s the lack of standardized data sharing. Even if a factory in Poland has perfect inventory, if they’re still using fax machines to report to their U.S. client, AI can’t help. We need universal digital tracking - not just for drugs, but for every critical component. It’s expensive, but it’s the only way forward.

Michael Whitaker-28 December 2025

While I appreciate the sentiment expressed herein, I must respectfully contend that your framing is fundamentally flawed. The notion that ‘patients should demand better’ implies agency where none exists under the current neoliberal regulatory architecture. The real issue is not consumer awareness - it is the structural disempowerment of the patient-subject within a capitalist-medical complex that commodifies life itself. You are merely rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.