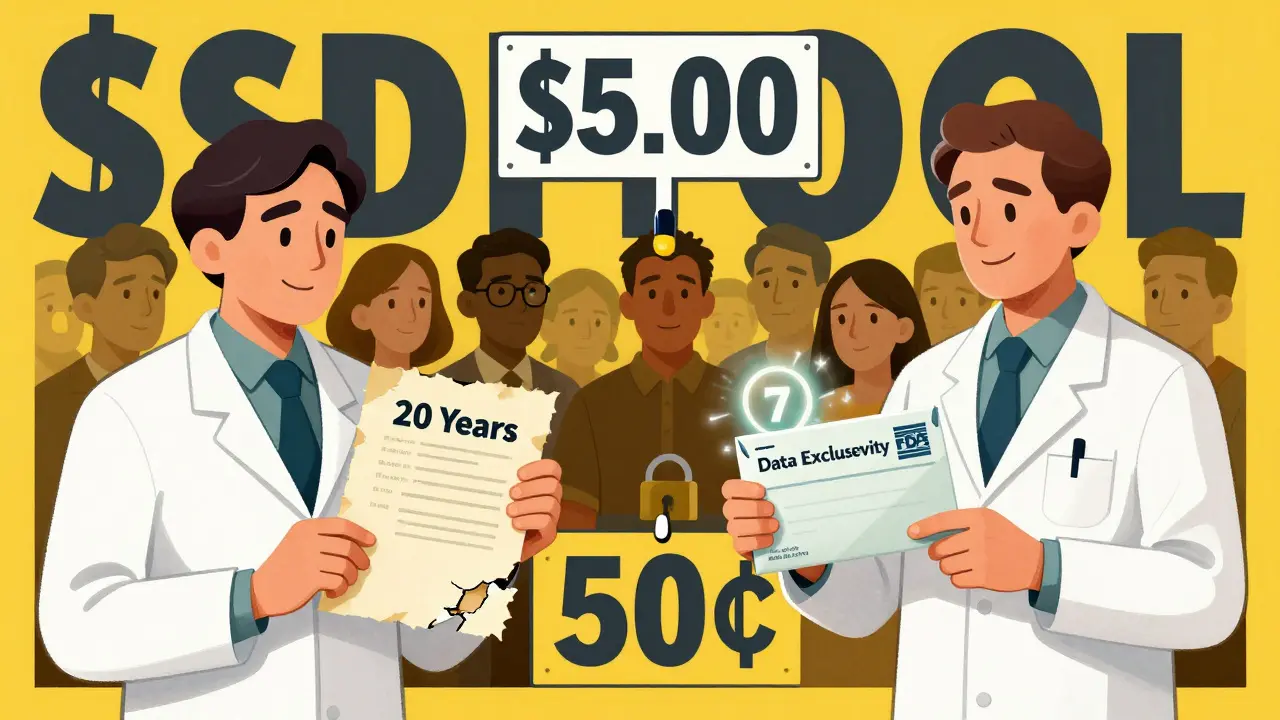

When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just get a brand name and a flashy ad campaign. It gets legal shields - two of them, actually. One is a patent. The other is market exclusivity. And if you think they’re the same thing, you’re not alone. But they’re not. They work differently, they’re granted by different agencies, and they can make the difference between a drug costing $5 a pill or 50 cents. Understanding this isn’t just for lawyers or pharma execs. It’s for anyone who’s ever wondered why some drugs stay expensive for years after their patent "expires."

Patent Exclusivity: The Legal Lock

A patent is a government-granted monopoly on an invention. In pharma, that usually means a new chemical compound, a specific way to make it, or a new use for an old one. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) issues these. Once granted, the patent holder can sue anyone who tries to copy the drug without permission.

On paper, patents last 20 years from the date they’re filed. But here’s the catch: most drugs take 10 to 15 years just to get approved by the FDA. That means by the time the drug actually hits shelves, you’ve already used up half your patent life. A drug filed in 2010 might not even be on the market until 2020 - leaving only 10 years to make back the $2.3 billion it cost to develop.

That’s why companies get extensions. The law lets them apply for Patent Term Extension (PTE) to make up for time lost during FDA review. The max extension? Five years. And the total time a drug can be protected after approval? No more than 14 years. So even with extensions, real-world patent protection rarely hits 20 years.

Patents also come in layers. The strongest is the composition of matter patent - it covers the actual molecule. But companies often file secondary patents: for a new pill coating, a different dosage, or a new way to use the drug. These don’t stop generics from making the same molecule - just from using the specific method or formulation covered by the patent. In fact, 68% of patents listed in the FDA’s Orange Book are secondary patents, not the core invention.

Market Exclusivity: The FDA’s Secret Weapon

Now here’s where things get weird. Market exclusivity has nothing to do with patents. It’s granted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) - not the USPTO. And it doesn’t care if the drug is new or old. It cares about the data.

When a company develops a new drug, it runs expensive clinical trials. The FDA reviews that data to decide if the drug is safe and effective. Market exclusivity says: "You spent the money, you did the work. For X years, we won’t let anyone else use your data to get their version approved."

This is called data exclusivity. It’s not about stopping generics from making the same chemical - it’s about stopping them from copying your clinical proof. And here’s the kicker: you can get this even if the drug isn’t patentable. Take colchicine. It’s been used since ancient Egypt to treat gout. But in 2010, Mutual Pharmaceutical got 10 years of market exclusivity for a reformulated version. Why? Because they submitted new clinical data. The FDA didn’t care that the drug was 3,000 years old. They cared that the data was new.

Here’s how market exclusivity breaks down:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE): 5 years. No one can submit an application for a generic version during this time.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 U.S. patients). This one doesn’t care about patents - it kicks in automatically.

- Pediatric Exclusivity: +6 months. Add this if you do extra studies on kids. Since 1997, this has added $15 billion in revenue to drugmakers.

- Biologics: 12 years. This is for complex drugs made from living cells - like Humira or Enbrel. Unlike small-molecule drugs, biologics can’t be copied exactly, so the FDA created this longer window.

- First Generic Applicant: 180 days. If a generic company challenges a patent and wins, they get this bonus period to be the only generic on the market.

When They Overlap - And When They Don’t

Here’s the real-world picture: most drugs have both. But not all. According to FDA data from 2021:

- 27.8% of branded drugs have both patent and market exclusivity.

- 38.4% have patents but no exclusivity.

- 5.2% have exclusivity but no patent.

- 28.6% have neither.

That 5.2%? That’s the sneaky part. These are drugs with no patent protection - maybe the molecule is too old, or the patent expired - but the FDA still won’t let generics in because of exclusivity. In 2021, 78% of drugs with exclusivity but no patent still had zero generic competition. That’s not a coincidence. That’s the system working as designed.

Take Trintellix, an antidepressant. Its composition patent expired in 2021. But because it had 3 years of market exclusivity, no generic could enter until 2024. Teva Pharmaceuticals lost an estimated $320 million in revenue because they didn’t realize exclusivity was still active. It wasn’t a patent issue. It was a paperwork issue.

Why This Matters for You

When you see a drug price jump - like colchicine going from 10 cents to $5 a pill - it’s not because the cost of making it changed. It’s because exclusivity locked out competition. And when exclusivity ends, prices can drop 80-90% overnight.

But here’s the twist: companies don’t always claim all the exclusivity they’re entitled to. Scendea Consulting found that between 2018 and 2022, 22% of drugmakers missed out on at least one exclusivity period. That’s an average of 1.3 years of lost protection per product. Why? Because the rules are confusing. The FDA requires specific filings. Missing a deadline, mislabeling a submission, or not proving the data was "essential to approval" can cost millions.

And it’s not just big pharma. Small biotech firms often assume their patent = market control. But 43% of those surveyed by BIO admitted they got burned by this mistake. They spent years and millions developing a drug, only to find out generics could enter because they never filed for exclusivity.

What’s Changing Now?

The system is under pressure. The FDA launched its Exclusivity Dashboard in September 2023 - a public tool that shows exactly when each drug’s exclusivity period ends. Generic manufacturers are now racing to file applications the moment exclusivity expires.

Meanwhile, lawmakers are pushing changes. The PREVAIL Act of 2023 proposes cutting biologics exclusivity from 12 years to 10. That could save billions in healthcare costs. And the FDA’s new 2024 rule requires more detailed justifications for exclusivity claims - meaning less room for loopholes.

But here’s the bottom line: patents are about invention. Market exclusivity is about data. One is a legal weapon. The other is a regulatory tool. You can have one without the other. And when you do, it’s often the exclusivity - not the patent - that’s holding prices high.

If you’re waiting for a generic to come out, check the FDA’s database. Look for the exclusivity date - not just the patent date. Because the real clock isn’t ticking on the patent. It’s ticking on the FDA’s decision.

Can a drug have market exclusivity without a patent?

Yes. Market exclusivity is granted by the FDA based on clinical data submitted for approval - not on whether the drug is patented. For example, colchicine had no active patent when it received 10 years of exclusivity because the company submitted new clinical data for a reformulated version. Orphan drugs also get 7 years of exclusivity regardless of patent status.

Do patents and market exclusivity always expire at the same time?

No. They’re calculated separately. A patent may expire 10 years after approval, while market exclusivity could last 5 or 7 years from approval. They can run at the same time, or one can end long before the other. The FDA doesn’t synchronize them - they operate independently.

Why do some drugs stay expensive even after the patent expires?

Because market exclusivity is still active. The FDA won’t approve a generic version until its exclusivity period ends - even if all patents have expired. This is common with orphan drugs, biologics, and reformulated versions of older drugs. The patent expiration date is not the only gatekeeper.

Can a generic drug enter the market before patent or exclusivity ends?

Only if the generic company legally challenges the patent through a Paragraph IV certification and wins in court. In that case, they get 180 days of exclusivity as a reward. But they can’t enter before exclusivity ends - even if they win the patent fight - because the FDA still blocks applications based on data exclusivity rules.

How do I find out when a drug’s exclusivity ends?

Use the FDA’s Exclusivity Dashboard, launched in September 2023. It lists every drug approved since 2018 with its exclusivity type, start date, and expiration date. You can also check the FDA’s Orange Book, which lists patents, but the Dashboard is the only source that shows regulatory exclusivity in real time.

11 Comments

Lyle Whyatt- 7 February 2026

Man, I never realized how wild this whole system is. I thought patents were the only thing blocking generics, but now I see it’s like a maze of legal and regulatory traps. That colchicine example? From 10 cents to $5? That’s not inflation-that’s corporate gymnastics. And the fact that the FDA protects data even for ancient drugs? That’s not innovation, that’s rent-seeking dressed up as policy. I’m not anti-pharma, but this feels like a loophole factory where the only winners are the ones who can afford teams of lawyers and regulatory consultants.

And don’t even get me started on orphan drugs. Seven years of exclusivity? For a disease that affects 100,000 people? I get the incentive, but when you combine that with patent extensions and pediatric add-ons, you’re looking at 20+ years of monopoly on a drug that could’ve been generic in five. It’s not just expensive-it’s morally weird.

I work in public health in Australia, and we’ve seen this play out with Hep C drugs. So much money spent on legal battles instead of patient access. The FDA dashboard is a start, but we need global transparency. Why should a kid in Lagos pay 10x more because a US company filed a paperwork form they didn’t even know existed?

This isn’t about innovation anymore. It’s about who gets to hold the keys to the pharmacy.

Random Guy- 8 February 2026

so like… the drug company spends 2.3 bil to make a pill… and then the fda says ‘nope, u can’t sell it for 5 years’… so they’re like ‘ok fine, here’s a new coating’ and now it’s 10 years??

bro. just let people make the same pill. we’re not asking for a new one. just the old one. at cost. like… how is this not a scam??

Brett Pouser- 9 February 2026

As someone who’s had to navigate this stuff with family members on expensive meds, this breakdown is *so* needed. I didn’t know market exclusivity even existed until my mom’s insulin price jumped after her patent expired. Turns out, the FDA blocked generics because of data exclusivity-no one told us. It’s not conspiracy, it’s just buried in fine print.

I’m glad the FDA put up that dashboard. Even if it’s clunky, at least it’s out there. My cousin’s a pharmacist in rural Ohio and she’s been telling me for years that patients are confused about why generics aren’t available. Now I can point them to the real reason: it’s not the patent-it’s the paperwork.

Also, that 22% of pharma companies missing exclusivity deadlines? That’s a whole other level of chaos. Imagine spending a decade developing a drug, then losing years of protection because someone forgot to check a box. Makes you wonder how many good drugs are still stuck behind bureaucratic errors.

Joshua Smith-10 February 2026

This is one of those topics that feels like insider baseball until it hits your wallet. I used to think ‘patent expiration = generic time’-naive, I know. Now I check the FDA dashboard before even asking my pharmacist about alternatives.

The pediatric exclusivity add-on is wild. $15 billion in extra revenue just for studying kids? I get the public health angle, but it’s also a brilliant financial play. Companies know they can tack on six months by doing minimal extra work. It’s not evil-it’s smart. But maybe too smart for its own good.

And the 180-day first-generic window? That’s like a lottery ticket for big pharma. One company wins, gets a monopoly on generics, and then *they* jack up prices. The system’s designed to be gamed.

Jessica Klaar-12 February 2026

I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients cry because they can’t afford their meds-even after patents expire. I didn’t understand why until I read this. That Trintellix example? $320 million lost because someone missed a filing? That’s not incompetence-that’s a system that rewards negligence over access.

It breaks my heart that people think the system is broken when it’s actually working exactly as designed. The goal isn’t to lower prices-it’s to protect revenue streams. And we’re the ones paying for it.

Can we fix this? Maybe. But first we have to stop calling it ‘innovation’ and start calling it ‘delayed competition.’

PAUL MCQUEEN-13 February 2026

so like… the fda is basically saying ‘we’re gonna let you charge 50x more for a pill because you did a study on 30 people with gout’?

and the patent office is just… along for the ride?

why do we even have a government if it’s just here to help billionaires make more money?

John Watts-13 February 2026

This is one of those topics that should be taught in high school. Seriously. Imagine if every student knew that ‘patent expiration’ doesn’t mean ‘cheap drug’-that’d change the whole conversation around healthcare.

And the fact that biologics get 12 years? That’s longer than most people’s college degrees. These aren’t pills-they’re complex biological machines. But still, 12 years? That’s not innovation protection, that’s a lifetime monopoly.

I’m all for rewarding research, but we need a better balance. Maybe tiered exclusivity? Shorter for common conditions, longer for ultra-rare diseases. And transparency. Always transparency.

Let’s make this simple: if you didn’t invent the molecule, you shouldn’t own the market forever.

Chima Ifeanyi-15 February 2026

Let’s deconstruct this with proper regulatory economics. The patent system is a classic Coasean bargain-exclusive rights incentivize R&D. But market exclusivity? That’s a Pigouvian distortion masquerading as a public good. The FDA’s data exclusivity creates artificial scarcity, which violates the principle of non-excludability in public health.

Furthermore, the 180-day first-generic incentive creates a perverse Nash equilibrium where litigation becomes the primary entry strategy rather than innovation. This is rent-seeking at scale.

And the 5.2% of drugs with exclusivity but no patent? That’s regulatory capture in action. The FDA is acting as a private gatekeeper for corporate IP, not a public health regulator.

Bottom line: this isn’t a policy failure. It’s a feature. Designed by lobbyists. Executed by bureaucrats. Enforced by courts. And paid for by patients.

Elan Ricarte-16 February 2026

ohhhhh so that’s why my insurance won’t cover the generic for my asthma inhaler even though the patent’s been dead for 3 years??

so the fda’s like ‘nah, we’re not lettin’ anyone else use that data, even if the molecule’s older than the constitution’??

bruh. this ain’t science. this is a monopoly casino run by lawyers in suits.

and the fact that companies miss exclusivity deadlines? that’s not incompetence-it’s greed. they’re playing the long game, betting that patients won’t notice until they’re already hooked.

we need a national audit. like, a real one. not some dashboard that looks pretty but doesn’t change a thing.

Angie Datuin-18 February 2026

Thank you for explaining this so clearly. I’ve been confused for years why some drugs never get cheaper.

Camille Hall-20 February 2026

One thing I wish more people understood: exclusivity isn’t just about money. It’s about trust. If the FDA doesn’t protect the data, companies won’t invest in studying kids, rare diseases, or reformulations. But if they protect it too long, people die because they can’t afford meds.

We need a middle ground. Maybe sunset clauses? Or mandatory price caps after exclusivity ends? Something that balances innovation with access.

And yes-check the FDA dashboard. It’s not perfect, but it’s the first step toward taking power back from the lawyers.