Primary Biliary Cholangitis (PBC) isn’t a disease you hear about often - until it affects you or someone you know. It’s a slow, silent killer of the liver’s bile ducts, mostly hitting women between 30 and 65. For decades, the only real treatment was ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a bile acid that helped many but didn’t work for nearly one in three. Now, in 2025, the landscape has changed dramatically. Two new drugs have arrived, one has been pulled off the market, and doctors are rewriting the rules on how to treat this autoimmune liver disease.

What Exactly Is Primary Biliary Cholangitis?

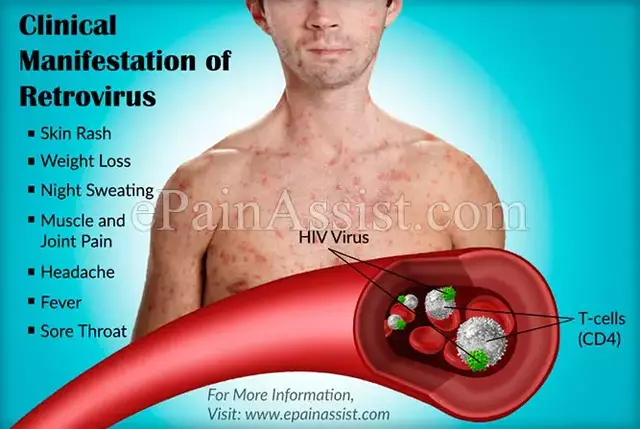

PBC isn’t just liver inflammation. It’s an autoimmune disorder where your immune system mistakenly attacks the small bile ducts inside your liver. These ducts are supposed to carry bile - a digestive fluid - from the liver to the small intestine. When they’re damaged, bile backs up, poisons liver cells, and causes scarring. Left untreated, that scarring turns into cirrhosis, and eventually, liver failure.

It’s not caused by alcohol or viruses. It’s not contagious. It’s linked to genes - especially variants in HLA-DR8, IL12A, and STAT4 - and triggered by things like urinary tract infections from E. coli. Women are nine times more likely to get it than men. About 1 in 3,000 people in the U.S. and Europe have it. Most are diagnosed after routine blood tests show high levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP), a liver enzyme that spikes when bile flow is blocked.

UDCA: The Old Standard, Still the First Step

For over 30 years, UDCA has been the go-to drug for PBC. It’s cheap, safe, and taken as a daily pill - usually 13 to 15 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. It works by replacing toxic bile acids with gentler ones, helping the liver flush out what it can’t process. It also calms down the immune system just enough to slow the attack on bile ducts.

The numbers don’t lie: about 60 to 65% of patients respond well to UDCA. Their ALP levels drop, their symptoms ease, and their chances of avoiding a liver transplant in 10 years jump from 69% to 87%. That’s huge. But here’s the catch - 35% of people don’t respond. Their ALP stays above 1.67 times the normal limit after a full year of treatment. For those patients, UDCA alone isn’t enough. Until recently, there was almost nothing else to try.

The Rise and Fall of Obeticholic Acid (Ocaliva)

In 2016, obeticholic acid (Ocaliva) was approved as the first real alternative to UDCA. It worked by activating a receptor called FXR, which helps regulate bile production and flow. In clinical trials, it lowered ALP better than placebo. Many patients and doctors celebrated.

But the downsides were serious. Over half of users had severe itching - worse than before treatment. Some had heart problems. A 2024 FDA safety review found patients with advanced liver damage had an 78% higher risk of death while taking Ocaliva. By September 2025, the FDA pulled it off the market entirely. The decision was unanimous: the risks outweighed the benefits, especially for people already showing signs of liver scarring.

Doctors who had been prescribing Ocaliva scrambled. Patients who had switched from UDCA to Ocaliva were left without a clear next step. Many were terrified. The withdrawal wasn’t just a drug recall - it was a crisis in patient care.

Enter Seladelpar (Livdelzi): The New Favorite

By December 2024, seladelpar (brand name Livdelzi) became the first new PBC drug approved after Ocaliva’s withdrawal. Developed by Gilead Sciences, it targets a different pathway - PPAR-delta - a protein that helps control inflammation and bile flow. It’s taken as a 5 mg pill daily, with the dose increased to 10 mg after four weeks.

The results? In the Phase 3 RESPONSE trial, 70% of patients saw their ALP drop by at least 15% - compared to just 20% on placebo. Even more impressive: 42% achieved ALP levels that were normal or close to normal. That’s higher than any other second-line drug ever tested for PBC.

It also helped with itching - the most miserable symptom of PBC. In trials, patients reported a 45% drop in itch intensity. That’s life-changing. People could sleep again. They could stop scratching their skin raw. Real-world data from 396 patients showed 85% stayed on seladelpar after a year, even after switching from Ocaliva.

There’s a catch: about 25% of patients get worse itching at first, especially in the first two weeks. But in 92% of those cases, it fades by week eight. Doctors now start low and go slow - and patients are warned to stick with it, even if it feels rough at first.

Elafibranor (Iqirvo): The Balanced Alternative

Elafibranor, approved in November 2024 under the name Iqirvo, is a dual PPAR-alpha/delta agonist. It’s simpler to take - one 80 mg pill a day, no titration needed. It’s also gentler on the liver’s lipid system, lowering triglycerides by 24%, which is helpful for patients with metabolic syndrome or fatty liver.

In the ELATIVE trial, 56% of patients reached the goal of reduced ALP and normal bilirubin (called a composite biochemical response). That’s strong, but not as high as seladelpar’s 70%. ALP normalization was 21% - lower than seladelpar’s 42%. Itch improvement was good, but not great: 38% reduction versus 45%.

Its biggest downside? About 18% of patients develop higher creatinine levels, a sign of reduced kidney function. That doesn’t mean kidney damage, but it does mean you need regular blood tests to monitor it. For patients with existing kidney issues, it’s not ideal.

Still, for people who can’t tolerate seladelpar’s early itching spike, or who need help with cholesterol and triglycerides, elafibranor is a solid second option.

How Doctors Decide What to Prescribe

The 2025 AASLD and EASL guidelines are clear: start with UDCA. All patients. No exceptions. If after 12 months your ALP is still above 1.67x normal, it’s time to move to second-line therapy.

Now, here’s the new algorithm:

- For patients with severe itching - even if they’re not in advanced liver disease - seladelpar is preferred. Its antipruritic effect is unmatched.

- For patients with high triglycerides or metabolic issues - elafibranor is a better fit.

- For patients who can’t tolerate either - fibrates (like fenofibrate) are used off-label. They’re cheap, and some studies show they help lower ALP, especially when combined with UDCA.

Monitoring is key. ALP levels are checked every 3 months during dose changes, then every 6 months once stable. A single high number doesn’t mean treatment failed - it’s the trend over time that matters. A sustained 15% drop in ALP, even without full normalization, still cuts the risk of death or transplant by 7% for every 10% drop.

What’s on the Horizon?

The pipeline is full. Setanaxib, a drug that blocks a protein linked to liver scarring, is in Phase 3 trials and could be available by 2027. Cenicriviroc, which targets inflammation pathways, is also showing promise. And the most exciting? A fecal microbiota transplant in pill form - VE-202 - is being tested. Early results suggest gut bacteria may play a role in triggering PBC. Fix the gut, maybe you fix the liver.

There’s also a new patient-reported outcome tool called PBC-40, now accepted by the FDA as a valid measure of how patients feel. That means future trials won’t just track ALP numbers - they’ll ask: Can you sleep? Can you work? Do you still feel like yourself?

Cost and Access: The Hidden Barrier

Here’s the ugly truth: these new drugs are expensive. Seladelpar costs about $500 a month out-of-pocket for many patients. Even with insurance, 28% of prior authorization requests for seladelpar are denied. Medicare requires proof of UDCA failure and ALP levels above 1.67x normal - which many primary care doctors don’t know how to document.

Patients in rural areas or smaller clinics often wait months to see a liver specialist. By then, the disease has progressed. The PBC Foundation’s Treatment Navigator tool helps patients understand what to ask for, and the AASLD’s mobile app gives doctors real-time dosing guidance. But access isn’t equal. Affordability is now the biggest challenge in PBC care - even more than the science.

What Patients Need to Know Right Now

If you’ve been diagnosed with PBC:

- Take UDCA exactly as prescribed. Don’t skip doses.

- Get your ALP checked every 3 months for the first year.

- If your ALP hasn’t dropped by 12 months, ask your doctor about second-line options.

- If you’re on Ocaliva, talk to your doctor immediately - you need to switch.

- Don’t give up if itching gets worse at first with seladelpar. It usually gets better.

- Join a patient community. The MyPBCteam survey showed 68% of people who switched from Ocaliva to seladelpar felt better within 8 weeks.

PBC isn’t curable yet. But it’s manageable. And for the first time in decades, patients have real choices - not just one drug that might work, but two that can change the course of the disease. The goal isn’t just to survive. It’s to live - without itching, without fatigue, without fear.

Is Primary Biliary Cholangitis the same as autoimmune hepatitis?

No. PBC attacks the small bile ducts inside the liver, while autoimmune hepatitis attacks the liver cells themselves. They’re both autoimmune, but they affect different parts of the liver and require different treatments. Some patients have both, which is called overlap syndrome - but that’s rare.

Can I stop taking UDCA if I start seladelpar or elafibranor?

No. All current guidelines say UDCA must continue alongside second-line drugs. Stopping UDCA increases the risk of disease progression. The new drugs work best when added to UDCA, not replacing it.

How do I know if my treatment is working?

ALP levels are the main marker. A drop of 15% or more after 12 months is a good sign. Normalization (below 1.5x ULN) is ideal, but even partial improvement cuts your risk of liver failure. Your doctor will also check bilirubin and liver enzymes. Don’t rely on symptoms alone - itching can improve even if ALP hasn’t dropped yet.

Why was Ocaliva pulled from the market?

Because long-term safety data showed increased risk of death in patients with advanced liver disease, plus severe itching and heart problems. The FDA concluded the risks outweighed the benefits, especially since safer alternatives like seladelpar are now available.

Are there any natural remedies or supplements that help with PBC?

No proven natural treatments exist. Some patients take vitamin D or calcium to protect bones (PBC increases osteoporosis risk), but these don’t treat the disease itself. Avoid herbal supplements like milk thistle - they’re unregulated and could harm your liver further. Always talk to your hepatologist before trying anything new.

How often should I see a liver specialist?

Every 6 to 12 months if you’re stable on treatment. If you’re newly diagnosed, starting a new drug, or have advanced disease, you’ll need to go every 3 to 4 months. Regular monitoring is critical - PBC progresses slowly, but it doesn’t stop.

Write a comment