Why generic drugs don’t hit the market at the same time everywhere

Ever wonder why a brand-name drug becomes cheap in the U.S. but still costs a fortune in Canada or Brazil? It’s not about supply or demand alone. It’s about exclusivity periods - the legal shields that keep generic versions off shelves. These rules vary wildly across countries, and they’re the real reason some people wait years for affordable versions of life-saving medicines.

The basic idea sounds simple: a drug company spends billions to develop a new medicine, gets a patent, and has exclusive rights to sell it. After that, generics can enter and drive prices down. But the reality? It’s a maze of patents, data protections, extensions, and legal loopholes - and every country plays by different rules.

Patents aren’t the whole story - exclusivity does more

Most people think a 20-year patent is the only thing blocking generics. It’s not. The patent clock starts ticking when the drug is first filed - often 10 to 12 years before it even hits the market. By the time the FDA or EMA approves it, only 6 to 10 years of patent life are left. That’s not enough to recoup the average $2.3 billion spent per drug.

That’s where exclusivity kicks in. It’s not a patent. It’s a regulatory delay. Think of it as a government-mandated pause on generic competition, even if the patent has expired. The U.S., EU, Canada, Japan - they all use different versions of this tool.

The U.S. system: Complex, aggressive, and full of loopholes

The U.S. has the most complicated system. It layers multiple types of exclusivity on top of patents. For a brand-new chemical, you get 5 years of data exclusivity - meaning no generic can copy the clinical trial data to get approved. Then there’s 7 years for orphan drugs (for rare diseases), 3 years for new uses or formulations, and a 6-month bonus if the company does pediatric studies.

But the real game-changer is the 180-day exclusivity for the first generic company to successfully challenge a patent. That’s a huge incentive. One company can block all others from entering for half a year - and charge high prices during that time. That’s why some generics file patent challenges even when they’re not ready to sell - just to lock in that window.

There’s a darker side: pay-for-delay. Brand companies sometimes pay generics to stay off the market. The FTC called it anti-competitive. Courts have cracked down, but it still happens. In 2023, 78% of U.S. pharmacists reported delays in generic availability because of these settlements.

The EU: More predictable, less aggressive

Europe doesn’t have the 180-day prize. Instead, it uses an 8+2+1 model. Eight years of data exclusivity - generics can’t use the original company’s data to apply. Then two years of market exclusivity - even if they have approval, they can’t sell. And if the brand company proves the drug has major new benefits, they get an extra year.

This system is simpler. No patent challenges mean fewer lawsuits. No 180-day rush means less strategic gaming. But it also means less incentive for generics to take risks. Entry tends to be slower, but more orderly.

And here’s the catch: EU trade deals often export these rules. Countries like South Africa had to extend data exclusivity for HIV drugs because of agreements with the EU. That delayed generics by up to 11 years after patents expired.

Canada and Japan: Middle ground

Canada’s system looks a lot like the EU’s: 8 years of data protection, 2 years of market exclusivity. It’s balanced - enough to protect innovation, but not so long that generics are locked out for decades.

Japan is a bit different. They give 8 years of data exclusivity and 4 years of market exclusivity for new chemical entities. That’s longer than the EU’s market protection. But they don’t have a 180-day prize. Their system is tightening, though. In 2023, Japan’s drug agency announced plans to speed up generic approvals by simplifying patent reviews.

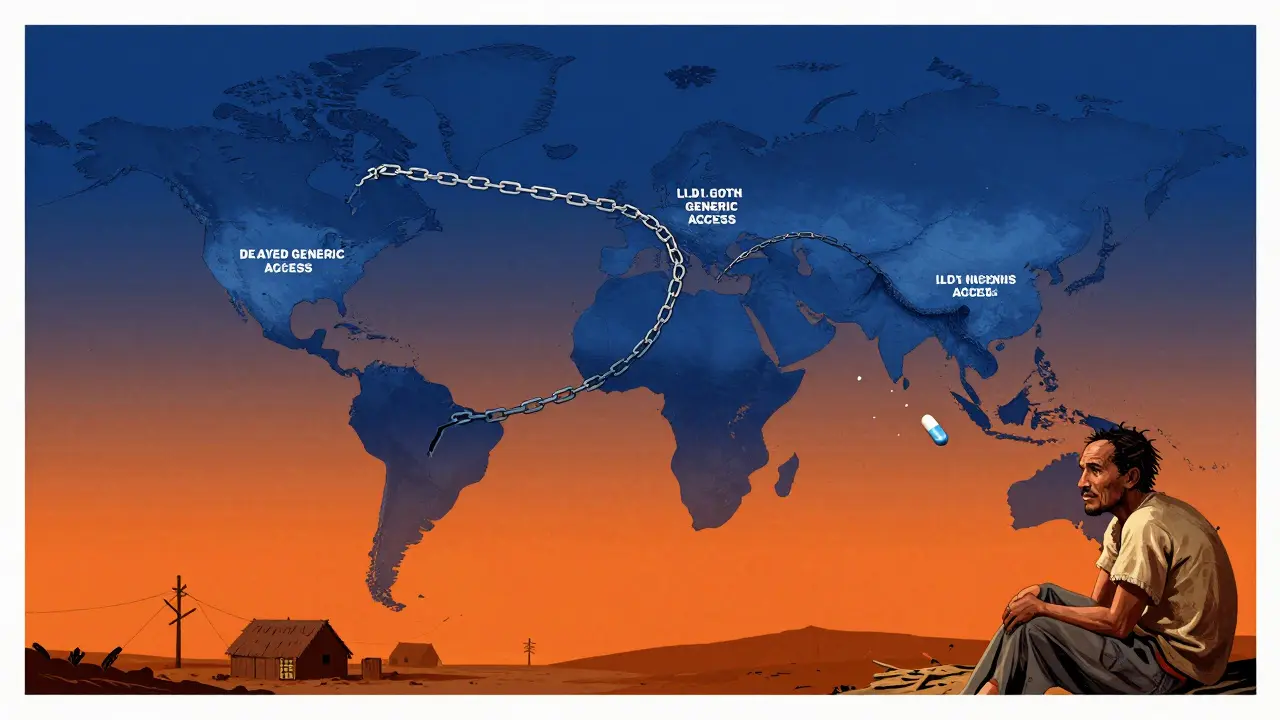

Developing countries: Caught in the middle

Low- and middle-income countries often get stuck with the worst of both worlds. They can’t afford the high prices of branded drugs, but their laws copy rich countries’ exclusivity rules - even when they don’t have the resources to enforce them.

WHO found that essential medicines reach generic status in high-income countries after 12.7 years on average. In low-income countries? 19.3 years. Why? Because trade agreements force them to adopt data exclusivity - even when their own patents have expired.

China raised its data exclusivity from 6 to 12 years in 2020. Brazil did the same in 2021. These moves aren’t about protecting innovation - they’re about meeting trade demands. The result? Millions of people waiting longer for affordable pills.

What’s changing in 2025 and beyond?

Pressure is building. In the U.S., lawmakers are pushing the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act to ban pay-for-delay deals. The EU is debating cutting data exclusivity from 8 to 5 years for some drugs - a huge shift.

But the industry fights back. PhRMA says without these protections, drug development would collapse. They point to the 14% failure rate in late-stage trials. It’s true - developing a new drug is risky and expensive.

But here’s the tension: the average drug now has 142 patents listed in the U.S. Orange Book. That’s not innovation. That’s a legal wall. Companies like Merck extend Keytruda’s effective market life from 8.2 to 12.7 years by stacking patents on minor changes. That’s called evergreening - and it’s legal.

Meanwhile, generic manufacturers like Teva say it costs $2-5 million just to navigate the patent maze for one drug. Most small generics can’t afford it. That’s why the top 10 generic companies now control 65% of the U.S. market. It’s becoming a game for giants.

What does this mean for you?

If you’re taking a brand-name drug, you might not see a generic for years - even after the patent expires. That’s not an accident. It’s by design.

If you’re in a country with weak enforcement or trade deals forcing long exclusivity, you might never get a cheap version. That’s not just a health issue - it’s a justice issue.

And if you’re in the U.S., you might get generics faster - but you might also pay more during that 180-day window because the first generic has no competition. The system rewards legal maneuvering, not affordability.

How to know when your drug will go generic

There’s no single database. But here’s how to track it:

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book for U.S. drugs - it lists patents and exclusivity dates.

- For EU drugs, search the EMA’s public register.

- Look for patent expiration dates on the manufacturer’s website - they sometimes disclose them.

- Follow news from generic companies like Teva, Mylan, or Sandoz - they announce challenges publicly.

And remember: even if the patent expires, exclusivity might still block generics. Always check both.

What’s next for global drug access?

The world is at a crossroads. On one side: profit-driven systems that protect innovation but delay access. On the other: public health systems that want affordable drugs now.

The WHO recommends aligning exclusivity periods with actual R&D costs - not corporate profits. That means shorter exclusivity for drugs that cost less to develop, and longer for truly novel therapies.

Until that happens, the gap between rich and poor countries will keep growing. And patients? They’ll keep waiting.

10 Comments

josh plum- 5 January 2026

So let me get this straight - Big Pharma pays generics to NOT sell cheaper drugs? And we call this a free market? This isn’t capitalism, it’s corporate feudalism. They’re literally buying time to keep you paying $1,000 for a pill that costs $2 to make. Wake up, people.

John Ross- 6 January 2026

The regulatory exclusivity frameworks are fundamentally misaligned with R&D cost recovery timelines. The 8+2+1 EU model introduces a non-patent IP barrier that decouples market entry from patent expiration - a structural inefficiency that distorts competitive dynamics in the generic biologics space. Data exclusivity, while ostensibly a trade-off for innovation incentives, creates artificial monopolistic rents that violate first-mover equilibrium assumptions in pharmaceutical economics.

Clint Moser- 7 January 2026

uuhh wait so the fda lets pharma companies file like 142 patents on one drug??? like... is this legal?? or is the whole system rigged by lobbyists?? i read somewhere that the orange book is basically a secret club where big pharma writes their own rules and the fda just rubber stamps it... someone pls confirm this is not a conspiracy...

Ashley Viñas- 8 January 2026

Honestly, it’s embarrassing that the U.S. still lets this happen. We’re the richest country on earth, and we’re letting pharmaceutical companies hold patients hostage for profit. The fact that pediatric bonuses and orphan drug extensions are used to extend monopolies on blockbuster drugs like Keytruda isn’t innovation - it’s exploitation. If you’re okay with this, you’re complicit.

Brendan F. Cochran- 9 January 2026

America builds the drugs, we pay for the R&D, and then other countries free-ride on our innovation? Nah. If you want cheap pills, go to India. We don’t owe the world affordable medicine just because they can’t afford to invest in science. This isn’t charity - it’s capitalism. Stop whining.

jigisha Patel- 9 January 2026

The disparity in generic access timelines between high-income and low-income nations is statistically significant (p < 0.001) and correlates strongly with TRIPS-plus provisions in bilateral trade agreements. The 6.6-year lag in generic availability in LMICs is not a market failure - it is a policy artifact of neocolonial intellectual property transfer.

Jason Stafford-11 January 2026

They’re not just extending patents - they’re weaponizing the legal system. Every single one of those 142 patents? A trap. Every pay-for-delay deal? A bribe. Every time a generic company files a challenge just to lock the market? That’s not competition - that’s collusion with a courtroom. And the FDA? They’re asleep at the wheel. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a rigged casino.

Justin Lowans-12 January 2026

I get that drug development is risky and expensive - but the system’s become a feedback loop where profit is prioritized over people. What if we restructured exclusivity to reward true innovation - like first-in-class drugs - and capped it at 5 years for me-too drugs? That’d still protect R&D but stop the endless patent stacking. We could save millions of lives and still fund real breakthroughs.

Ethan Purser-14 January 2026

I used to think capitalism was about freedom. Now I see it’s about control. Control over life. Control over death. Control over whether a single mother in Brazil can afford insulin for her child. This isn’t about science or innovation anymore - it’s about power. And the people who hold that power? They sleep in mansions while kids in Lagos wait for pills that should’ve been free decades ago.

Doreen Pachificus-14 January 2026

I just checked the Orange Book for my asthma inhaler. Patent expired in 2022. But exclusivity? Still active until 2026. So I’m paying $400 for something that could be $20. And no one talks about this. Why is this not front-page news every day?