Before 1984, if you needed a cheap version of a brand-name drug, you were out of luck. Generic drugs were rare, expensive to make, and legally risky. The system was stacked against anyone trying to bring a lower-cost version to market-even if the chemical was identical. Then came the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, a law that didn’t just tweak the rules-it rebuilt the entire foundation of how generic drugs get approved in the U.S.

What the Hatch-Waxman Act Actually Did

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, was a rare moment of compromise in U.S. politics. Sponsored by Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, it brought together brand-name drug makers and generic manufacturers to agree on something neither side fully loved-but both could live with. The law had two clear goals: make it easier for generic drugs to reach patients, and give brand-name companies a little extra time to profit from their patents. Before this law, generic companies had to run full clinical trials to prove their drug was safe and effective. That meant spending millions and waiting years-even though the drug was chemically identical to the brand-name version. The FDA had already approved the original. Why redo all the testing? Hatch-Waxman fixed that by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Instead of repeating clinical trials, generic makers now only had to prove their version was bioequivalent-meaning it delivered the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate. That cut development costs by 80-90%. Suddenly, making a generic drug wasn’t a gamble-it was a business.The Patent Game: How Generic Companies Could Challenge Brand-Name Patents

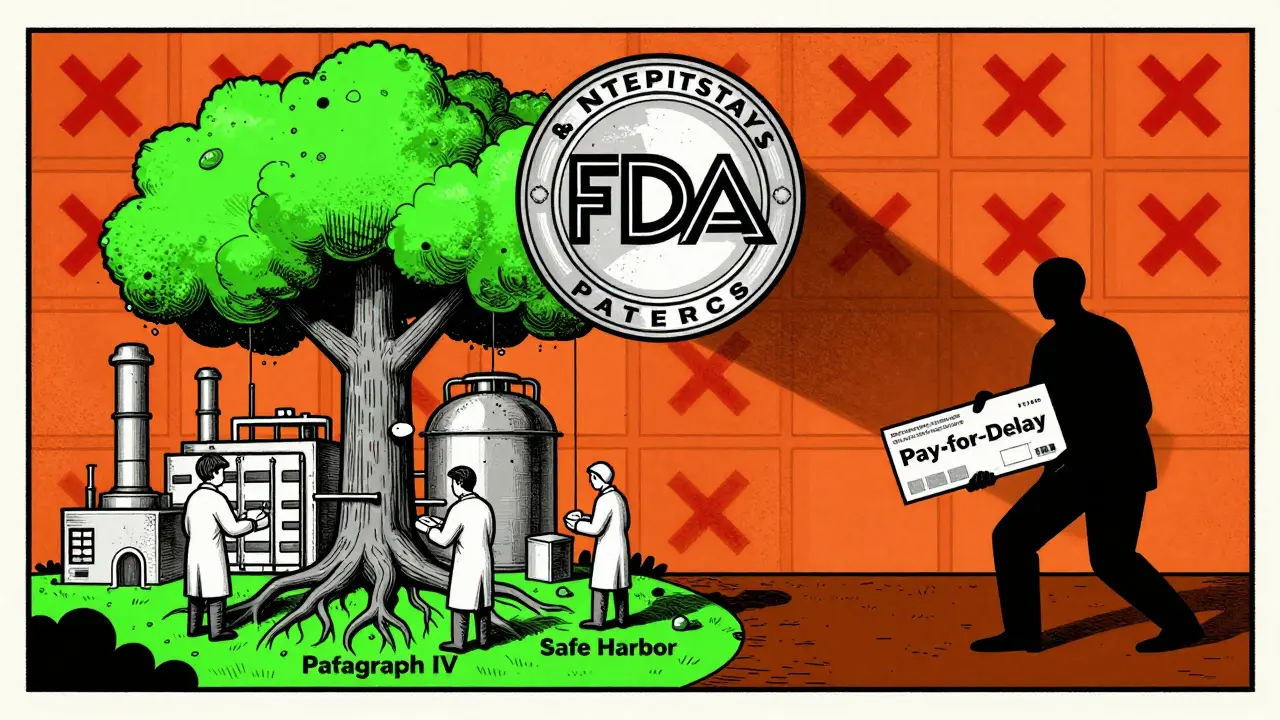

But here’s the twist: brand-name drugs are protected by patents. If a patent was still active, the generic couldn’t legally sell its version-even if it was ready to go. So how did Hatch-Waxman allow generics to enter before patents expired? It created something called the Orange Book, a public list of all patents tied to brand-name drugs. When a generic company files an ANDA, it must certify how it handles those patents. There are four options, but only one really changed the game: Paragraph IV certification. This is where a generic company says, “Your patent is invalid, or we don’t infringe it.” That’s a direct legal challenge. And if they’re the first to file it, they get a huge reward: 180 days of exclusive rights to sell their generic version. No other generics can enter the market during that time. That’s a massive financial incentive. One company could make hundreds of millions in those six months. To balance that, Hatch-Waxman gave brand-name companies a shield: if they sued the generic for patent infringement within 45 days of being notified, the FDA had to wait 30 months before approving the generic. That gave the brand-name company time to fight in court. But it also meant the generic had to be ready to go the moment the patent expired-or won the lawsuit.The Safe Harbor: Why Generic Companies Could Start Before the Patent Ran Out

Here’s another key part: the safe harbor provision (35 U.S.C. § 271(e)(1)). This says that using a patented drug to develop data for FDA approval isn’t patent infringement. Before this law, companies like Bolar Pharmaceutical got sued just for testing a drug before the patent expired-even if they weren’t selling it yet. The court said that was illegal. Hatch-Waxman changed that. Now, generic companies can start testing, tweaking, and preparing their product years before the patent ends. They can build manufacturing lines, train staff, and run bioequivalence studies-all while the brand-name drug is still under patent. That’s why, when a patent expires, there’s often a flood of generics on the market within weeks.

What Brand-Name Companies Got in Return

The law wasn’t just a win for generics. Brand-name companies got something too: patent term restoration. The FDA’s approval process could take years. A drug might have 20 years of patent life, but by the time it hit shelves, only 8-10 years were left. Hatch-Waxman let companies apply to extend their patent by up to five years to make up for that lost time. They also got new forms of market exclusivity. A new chemical entity? Five years of exclusivity. A new use for an old drug? Three years. A drug for a rare disease? Seven years. These weren’t patents-they were regulatory blocks. No generic could even file for approval during that time, regardless of patent status.The Numbers Don’t Lie: How the Law Changed Everything

Before 1984, less than 19% of U.S. prescriptions were filled with generics. By 2023, that number was nearly 90%. Today, more than 10,000 generic drugs are available in the U.S. They cost, on average, 80-85% less than their brand-name counterparts. That’s hundreds of billions saved by patients, insurers, and taxpayers every year. The law didn’t just lower prices-it created an entire industry. Companies like Teva, Mylan, and Sandoz grew from small players into global giants because of Hatch-Waxman. It turned generic drugs from a niche side business into the backbone of American pharmacy.

But It Wasn’t Perfect

The law was designed as a balance. But over time, the scales tipped. Brand-name companies found ways to game the system. One tactic? “Evergreening”-filing new patents on minor changes like a new pill coating or dosage form to reset the clock. Another? “Pay-for-delay” deals, where a brand-name company pays a generic maker to delay its launch. The Federal Trade Commission found 668 of these deals between 1999 and 2012, costing consumers an estimated $35 billion a year. The 180-day exclusivity period also led to chaos. Companies would race to file Paragraph IV certifications on the same day, hoping to share the exclusivity. Some even filed applications weeks before the patent expired just to be first in line. The FDA had to step in and say, “If you file on the same day, you share the 180 days.” And then there’s the issue of delays. In 2012, the average ANDA review took 30 months. By 2022, thanks to user fees from generic companies under GDUFA (Generic Drug User Fee Amendments), that dropped to under 12 months. But backlogs still happen. Some applications sit for over a year.Is the Balance Still Right in 2026?

The original compromise was meant to encourage innovation while ensuring access. But today, brand-name drugs cost more than ever. Some of the most expensive medicines in the world are still protected by layers of patents and exclusivity that weren’t envisioned in 1984. Congress has tried to fix it. The 2023 Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act aimed to crack down on pay-for-delay deals. But enforcement is weak. The FTC can investigate, but it can’t stop these deals unless it takes them to court-and that takes years. Meanwhile, the FDA continues to update its rules. It’s now pushing for more transparency in the Orange Book. It’s cracking down on frivolous citizen petitions-where brand-name companies file complaints just to delay generic approvals. And it’s trying to make sure the 180-day exclusivity isn’t abused by companies that never even launch their product.Why This Matters to You

If you’ve ever filled a prescription and paid $5 for a drug that used to cost $300, you’ve seen Hatch-Waxman in action. It’s why your insulin, your blood pressure pill, your antibiotic is affordable. It’s why pharmacies stock generics alongside brand names. But it’s also why some drugs remain outrageously expensive. The law didn’t solve high drug prices-it just changed how they’re structured. The real challenge now isn’t whether generics can get approved. It’s whether the system still serves patients-or just the companies that profit from it. The Hatch-Waxman Act didn’t end the fight over drug prices. But it gave patients a weapon: competition. And that’s something no patent can fully take away.What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act, formally the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, is a U.S. law that created the modern system for approving generic drugs. It established the ANDA pathway, allowing generics to prove bioequivalence instead of running full clinical trials. It also gave brand-name drug makers patent term extensions and created legal tools to resolve patent disputes.

How did the Hatch-Waxman Act change generic drug approval?

Before Hatch-Waxman, generic companies had to submit full New Drug Applications (NDAs) with clinical trial data, just like brand-name makers. That was expensive and slow. After the law, they could file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA), proving only that their drug is bioequivalent to the brand-name version. This cut approval time and costs by up to 90%.

What is Paragraph IV certification?

Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement a generic drug maker files with its ANDA, claiming that a brand-name drug’s patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed. It’s a direct challenge to the patent. The first company to file a Paragraph IV certification gets 180 days of market exclusivity, which makes it a powerful incentive to challenge weak or overreaching patents.

Why do some brand-name drugs stay expensive even after patents expire?

Brand-name companies often use tactics like “evergreening”-filing new patents on minor changes-or file citizen petitions to delay generic approvals. They may also strike “pay-for-delay” deals, paying generic makers to hold off on launching their cheaper version. These tactics can block competition for years, keeping prices high even after the original patent expires.

How much do generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system?

In 2023, generic drugs accounted for about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but only about 20% of total drug spending. They cost, on average, 80-85% less than brand-name versions. That translates to more than $300 billion in annual savings for patients, insurers, and government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

15 Comments

Kiruthiga Udayakumar- 7 January 2026

So let me get this straight-this law let generic companies steal brand-name drugs’ formulas but still let Big Pharma extend patents? That’s not a compromise, that’s a heist with a law degree. 🤡

tali murah- 8 January 2026

Let’s be real: Hatch-Waxman was never about patients. It was about corporate chess. The 180-day exclusivity window? A velvet rope for the first corporate vulture to arrive. And don’t get me started on pay-for-delay-where pharma pays its own competitors to stay off the field. This isn’t capitalism. It’s collusion with a FDA stamp.

Patty Walters- 9 January 2026

Just wanted to clarify something real quick-Paragraph IV isn’t just ‘challenging’ patents, it’s a legal gamble. If you lose, you’re on the hook for damages. And yeah, the first filer gets 180 days, but if they don’t launch within 75 days after court resolution? The exclusivity vanishes. So many companies sit on it waiting for the perfect moment. It’s wild.

Phil Kemling-11 January 2026

It’s fascinating how a law meant to balance innovation and access ended up creating a new kind of monopoly-one built not on patents, but on regulatory loopholes. The real tragedy? The system still assumes that ‘competition’ means more players, not lower prices. But if the first generic gets 180 days of monopoly pricing, is that really competition? Or just a different flavor of exploitation?

Drew Pearlman-11 January 2026

Look, I know people hate pharma, but without Hatch-Waxman, we wouldn’t have generic insulin, or generic HIV meds, or generic antidepressants. I’ve seen people choose between rent and their meds. This law saved lives. Yeah, it’s flawed-no law is perfect-but the alternative? No generics at all. That’s not progress, that’s cruelty.

Jeffrey Hu-11 January 2026

Actually, the 80-85% price drop is misleading. That’s retail price. The real cost savings come from bulk purchasing by insurers and PBMs. Most patients still pay copays, and those haven’t dropped proportionally. Also, the ANDA backlog? It’s not just FDA slowness-it’s companies filing incomplete applications on purpose to delay competitors. Sneaky.

Jerian Lewis-12 January 2026

People act like this law was some noble victory for the little guy. Newsflash: it was written by lobbyists. The ‘safe harbor’? That was a gift to generic companies so they could start manufacturing while the patent was still active. Meanwhile, patients still pay $500 for a pill because the system rewards delay, not access.

Diana Stoyanova-13 January 2026

Y’all need to stop acting like this is just about drugs. This is about dignity. Imagine needing a daily pill to live-and having to beg your insurance for it because the company owns the patent and the price tag. Hatch-Waxman didn’t fix that. But it gave us a weapon. And now? We need to sharpen it. 🛠️💔

Elisha Muwanga-15 January 2026

Let’s not forget: this law was made by Americans, for Americans. Now we’re exporting it globally while foreign governments use it to undercut U.S. drug innovation. We built the engine of generic competition, and now other countries are riding it while we pay the bills. That’s not free trade. That’s economic self-sabotage.

Lindsey Wellmann-15 January 2026

OH MY GOD. I JUST REALIZED-EVERY TIME I BUY GENERIC ADDERALL FOR $10, I’M PARTICIPATING IN A 40-YEAR-OLD POLITICAL MASTERPIECE. I FEEL LIKE A REVOLUTIONARY. 🎉💊 #HatchWaxmanHero

Maggie Noe-15 January 2026

There’s a quiet beauty in this law. It didn’t outlaw greed-it just made it compete. The genius was letting generics challenge patents, but forcing them to do it in court, not in the shadows. It’s like giving the underdog a microphone and a lawyer instead of a slingshot. Not perfect, but it’s the closest we’ve gotten to fairness in pharma.

Catherine Scutt-17 January 2026

So you’re telling me the whole system runs on loopholes and legal chess? And we call this healthcare? I’m not even mad. I’m just disappointed. Like, I expected more from a country that claims to value innovation.

Darren McGuff-19 January 2026

For those wondering why the FDA backlog dropped from 30 to 12 months-it’s because of GDUFA. Generic companies pay fees to the FDA to fund reviewers. It’s not charity-it’s a user-fee model. And guess what? It works. We need more of this in public health.

Gregory Clayton-20 January 2026

Generic companies are the real MVPs. They don’t have fancy labs or IPOs. They just make pills cheaper. And somehow, the media treats them like villains. Meanwhile, the brand names charge $100K for a cancer drug and get Nobel prizes. Wake up.

Alicia Hasö-21 January 2026

To everyone who says ‘the system is broken’-you’re right. But let’s not throw out Hatch-Waxman. Let’s fix it. Close the pay-for-delay loophole. Limit evergreening. Require transparency in the Orange Book. The framework works. The players just stopped playing fair. We can still win this game.