When a pharmaceutical company changes even a small part of how a drug is made - like swapping out a machine, moving a step to a different room, or tweaking the raw material supplier - it’s not just an internal operational tweak. It’s a regulatory event. And if handled wrong, it can lead to a warning letter, a product recall, or even a shutdown of production. The rules around manufacturing changes aren’t suggestions. They’re legal requirements under U.S. law, enforced by the FDA, and mirrored in similar ways across Europe, Canada, and other major markets.

Why Do Manufacturing Changes Need Approval?

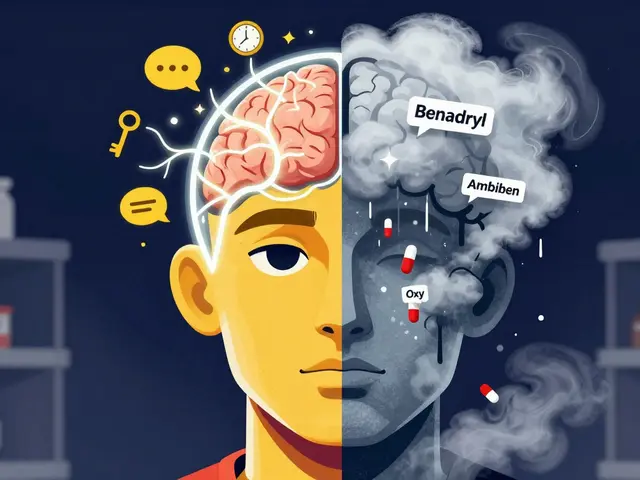

Think of a drug like a recipe. If you change the oven temperature, the flour brand, or the mixing time in a cake recipe, the final product might still look the same - but it could taste different, dry out faster, or even make someone sick. The same applies to medicines. A change in the manufacturing process can affect the drug’s identity, strength, purity, or potency. Even tiny shifts in how an active ingredient is synthesized or how a tablet is compressed can alter how the body absorbs it. That’s why regulators demand control. The goal isn’t to slow things down - it’s to make sure patients get the same safe, effective medicine every time, no matter when or where it was made.

The FDA’s Three-Tier System: PAS, CBE-30, and Annual Reports

The U.S. FDA breaks manufacturing changes into three clear categories based on risk. This isn’t arbitrary - it’s based on decades of data and real-world outcomes.

- Prior Approval Supplement (PAS): This is for major changes. If you’re switching to a new synthesis route for the active ingredient, moving production to a brand-new factory, or installing equipment that changes critical process parameters, you must get FDA approval before you ship any product made with the change. This can take 6 to 12 months. Companies often delay these submissions because they’re resource-heavy - but skipping this step is risky. In 2023, the FDA issued four warning letters specifically for companies that implemented major equipment changes without PAS approval.

- Changes Being Effected in 30 Days (CBE-30): This is for moderate changes. You can make the change and ship product immediately - but you must notify the FDA at least 30 days before you do. Examples include replacing a tablet press with an identical model from the same manufacturer, or changing the supplier of a non-critical excipient with a qualified alternative. The key here is ‘equivalent.’ If the new equipment has the same operating principle, same materials, and same critical dimensions, it’s likely CBE-30. If there’s any doubt, it’s safer to assume it’s PAS.

- Annual Report: These are minor changes with little to no impact on quality. Think moving a labeling station within the same cleanroom, or updating a software patch on a non-critical machine. You don’t need approval or even advance notice. But you must document it and include it in your annual report submitted to the FDA by the anniversary date of your original approval.

How Other Regulators Compare

The FDA isn’t the only player. Europe, Canada, and global bodies have their own rules - and they don’t always line up.

In Europe, the EMA uses a three-type system: Type IA (minor, notify within 12 months), Type IB (moderate, must be approved before implementation), and Type II (major, full review before change). The big difference? The EMA doesn’t have a ‘notify and go’ option like the FDA’s CBE-30. Even moderate changes in Europe require approval before you act. That can slow things down - but it also reduces ambiguity.

Health Canada mirrors the FDA’s structure: Level I (PAS equivalent), Level II (CBE-30 equivalent), and Level III (annual report). But their definitions of ‘equivalent’ equipment are stricter. For example, changing from a rotary tablet press to a linear one - even if output is the same - is considered a Level I change in Canada, while the FDA might allow it as CBE-30 if process parameters are unchanged.

For global manufacturers, this creates a headache. A change that’s minor in the U.S. might be major in Europe. That’s why companies with international products often design their change control systems to meet the strictest standard - usually EMA’s - to avoid compliance gaps.

What Triggers a Major Change (PAS)?

Not all equipment swaps are equal. Here’s what actually pushes a change into PAS territory:

- Changing the chemical synthesis route for an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API)

- Moving production of a critical step to a new facility

- Switching from batch to continuous manufacturing

- Introducing a new sterilization method (like switching from autoclave to radiation)

- Changing the source of a critical raw material that affects drug stability

- Modifying equipment that directly impacts Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) - like particle size, dissolution rate, or moisture content

The FDA’s 2021 guidance for biologics includes a table listing over 50 common changes and their recommended categories. It’s one of the clearest resources out there. But even with that, companies still get it wrong. In 2019, Apotex received a warning letter for classifying a major lyophilizer (freeze-dryer) replacement as a CBE-30. The FDA said the change altered critical process parameters and required PAS. The company had to recall 12,000 vials and halt production for months.

How Companies Actually Manage This

Large companies like Pfizer or Novartis have internal change classification systems that go beyond the FDA’s rules. They use risk-scoring tools - sometimes with 15+ criteria - to rate each change. Factors include:

- Impact on CQAs

- History of process stability

- Validation status of the affected step

- Supplier reliability

- Whether the change affects multiple products

Smaller companies don’t always have that luxury. A regulatory affairs specialist on Reddit shared that classifying a single tablet press replacement took their team 37 hours of meetings, data review, and legal review. Why? Because the API’s particle size specs were vague, and no one could be sure if the new machine would affect dissolution.

Most companies now use digital change management systems that auto-flag high-risk changes and link documentation to regulatory templates. But the human element still matters. A 2022 survey by ASQ found that regulatory professionals need 18 months of on-the-job training to consistently classify changes correctly.

Documentation Is Non-Negotiable

It’s not enough to say, ‘We did it right.’ You have to prove it. For any CBE-30 or PAS submission, you need:

- Updated facility diagrams showing new equipment placement

- Process validation reports for the changed step

- Comparative data from at least three consecutive batches made before and after the change

- Stability data showing the product still meets shelf-life specs

- A formal risk assessment using ICH Q9 principles - like Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

The FDA doesn’t ask for this just to be thorough. It’s because they’ve seen what happens when companies skip it. In 2022, 22% of all FDA warning letters were tied to improper change management - and 37% of those involved equipment changes.

What’s Changing in 2025?

The rules are evolving. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance pushes for using Quality Risk Management (ICH Q9) to make decisions less about checkboxes and more about actual risk. Companies piloting real-time monitoring - like sensors that track temperature, pressure, and moisture during production - are already using that data to justify lower regulatory burden. One company reduced their PAS submissions by 40% for certain changes by showing the system consistently stayed within validated limits.

The EMA introduced ‘Type IB accelerated’ pathways in January 2023, cutting review times for certain equipment changes from 60 to 30 days. And with the rise of advanced therapies - like gene and cell treatments - more changes are now falling into PAS territory. These products are so sensitive that even a minor equipment tweak can alter the final product’s safety profile.

By 2025, experts predict 40% of new change submissions will include real-time data to support approval. That’s a shift from ‘trust us’ to ‘here’s the proof, right here, in real time.’

What Happens If You Get It Wrong?

Ignoring or misclassifying a manufacturing change isn’t a slap on the wrist. Consequences are severe:

- Warning letters from the FDA - public and searchable

- Product recalls - costly and damaging to reputation

- Import alerts - blocking your product from entering the U.S.

- Consent decrees - court-enforced compliance plans with third-party auditors

- Loss of market access - especially in Europe or Canada if U.S. violations trigger international scrutiny

One company lost $87 million in revenue in 2022 after a misclassified change led to a recall of a chronic disease drug. The FDA didn’t fine them - they just stopped approving any new products until the issue was fixed.

Bottom Line: When in Doubt, Ask

The safest move isn’t to guess. If you’re unsure whether a change is CBE-30 or PAS, contact the FDA’s pre-submission program. It’s free. It’s confidential. And it’s designed for exactly this situation. The FDA says in their 2021 guidance: ‘If we disagree with your classification, we’ll tell you - but if you don’t ask, we’ll find out later when it’s too late.’

Manufacturing changes aren’t about slowing innovation. They’re about protecting patients. The system isn’t perfect - it’s complex, inconsistent across borders, and sometimes slow. But when done right, it’s what keeps every pill, injection, and inhaler you take safe and effective. Don’t cut corners. Document everything. And when in doubt, ask before you act.

What’s the difference between a PAS and a CBE-30?

A PAS (Prior Approval Supplement) requires FDA approval before you can ship any product made with the change. It’s used for major changes like switching to a new factory or changing how the active ingredient is made. A CBE-30 lets you make the change and ship product immediately, but you must notify the FDA at least 30 days before doing so. It’s for moderate changes, like replacing equipment with an identical model. The key difference is timing: PAS = wait for approval; CBE-30 = notify before shipping.

Can I make a manufacturing change and tell the FDA later?

Only for minor changes that go in your annual report. For moderate changes (CBE-30), you must notify the FDA 30 days before shipping. For major changes (PAS), you cannot ship the changed product until approved. If you make a change without proper notification, you’re in violation - and the FDA can issue a warning letter, recall your product, or block imports.

What counts as ‘equivalent’ equipment?

According to FDA guidance, ‘equivalent’ means the new equipment has the same principle of operation, same critical dimensions, and same material of construction. For example, swapping a tablet press from Brand A to Brand B is fine if both use the same compression force, die set size, and stainless steel contact surfaces. But if the new machine changes how powder flows or how pressure is applied, it’s no longer equivalent - and likely requires a PAS.

Do I need to run stability tests after every change?

For PAS and CBE-30 changes, yes - you need to show the product still meets its shelf-life specifications after the change. This usually means testing at least three batches made with the new process under real-world storage conditions. For annual report changes, stability data isn’t always required unless the change could theoretically affect it. But it’s still good practice to have it.

Why do some companies get warning letters for equipment changes?

Most often, it’s because they misclassified the change. A company might think replacing a pump is minor, but if that pump affects the mixing time or temperature - which impacts drug purity - it’s a major change. The FDA doesn’t care about intent. They care about impact. If the change affects Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs), and you didn’t submit the right type of application, you’re in violation. In 2023, four warning letters were issued specifically for this reason.

14 Comments

June Richards- 1 February 2026

Ugh, another FDA rant. I get it, changes are risky. But come on. 6-12 months for a PAS? We’re in 2025. My phone updates faster than this. 🙄

Jaden Green- 1 February 2026

The fundamental flaw in this entire system is the assumption that regulatory bodies possess any meaningful understanding of modern pharmaceutical manufacturing. The FDA’s three-tiered classification is a relic of analog-era thinking, predicated on rigid, binary categorizations that ignore the probabilistic nature of process variability. Real-time process analytics, multivariate statistical process control, and machine learning-driven predictive modeling have rendered these archaic frameworks obsolete - yet we cling to them like religious dogma, sacrificing innovation on the altar of bureaucratic inertia.

Lu Gao- 3 February 2026

I love how they say 'when in doubt, ask' - but then make it sound like you're begging for mercy. 😅 Like, yeah, I'll just email the FDA and hope they don't ghost me for 6 months. Meanwhile, my patients are running out of meds.

Angel Fitzpatrick- 4 February 2026

This whole thing is a cover-up. Big Pharma lobbies to keep the system confusing so small competitors can’t afford compliance. The 'PAS' isn't about safety - it's a tax on innovation. And don't get me started on the 'real-time monitoring' hype. Sensors? Please. They’re just replacing one bureaucracy with another - now with more data and fewer humans actually looking at it. The FDA’s '2023 draft guidance'? More like 2023 propaganda. They’re not protecting patients - they’re protecting their own budgets.

Melissa Melville- 4 February 2026

So let me get this straight - if I change the brand of a screw on a tablet press, I need a 12-month wait? In the U.S.? In 2025? 😂

Ed Di Cristofaro- 5 February 2026

People don’t get it. This isn’t about red tape - it’s about not killing someone because someone cut a corner to save $50k. I’ve seen what happens when you skip the docs. It ain’t pretty.

Lilliana Lowe- 5 February 2026

The assertion that 'equivalent equipment' is objectively definable is fundamentally flawed. The FDA’s guidance lacks sufficient operational specificity to permit consistent application across diverse manufacturing environments. One must therefore infer intent from contextual variables - a practice that is inherently subjective, and thus, legally untenable. The entire classification framework is a house of cards built on ambiguous semantics.

Lisa Rodriguez- 5 February 2026

I work in a small biotech and we just went through a CBE-30 for a new mixer. Took 4 months, 3 consultants, and 12 internal meetings. The system is broken. But I get why it exists. We’re not just making pills - we’re making trust. So yeah, I’d rather be slow than sorry. Still… man, it’s exhausting.

Bob Cohen- 7 February 2026

Honestly? I think the FDA’s system is kinda genius. It’s not perfect, but it forces you to think before you act. I used to roll my eyes at the paperwork. Now? I’m grateful for it. My sister takes a med that’s made in three countries - and I know it’s the same because of this stuff. So yeah, it’s slow. But it works.

Nidhi Rajpara- 8 February 2026

This article is very informative. But I think the FDA should adopt EMA standards completely. India has many generic manufacturers and we face huge problems with U.S. import alerts. The inconsistency is causing us great loss. Thank you for sharing.

Donna Macaranas- 9 February 2026

I just read this at 2am after a 14-hour shift. I’m tired. But I’m also glad someone finally explained this in plain English. Thank you.

Sami Sahil- 9 February 2026

Bro if you think this is bad, try getting a change approved in India 😅 We have to submit 3 copies, get 7 stamps, and pray to 3 gods. But hey - at least the FDA doesn’t make you bring chai to the inspector.

Nancy Nino-10 February 2026

It is imperative to underscore that the regulatory frameworks delineated herein constitute not merely procedural formalities, but rather, non-negotiable pillars of public health integrity. The notion that 'speed' should supersede 'safety' is a fallacy that has, on multiple occasions, resulted in catastrophic outcomes. One must, therefore, approach each change with the solemnity of a life-or-death decision - because, in truth, it always is.

Naomi Walsh-11 February 2026

The FDA’s CBE-30 is a joke. In Europe, we don’t play these games. If it’s not PAS, it’s IB. No 'notify and go' nonsense. That’s why European drugs are more consistent. And yes, I’ve worked in both. The U.S. system is a liability.