How Patents Keep New Drugs Coming - and Why Generics Can’t Show Up Too Soon

Imagine spending 12 years and $2.6 billion to create a new drug. You’ve tested it on thousands of people, navigated endless FDA reviews, and finally got approval. Then, the moment it hits the market, a company copies your formula, sells it for 80% less, and takes over your customers. That’s the problem patent law was built to solve - not to block competition, but to make sure innovation still pays off.

The U.S. system doesn’t just hand out patents and walk away. It’s a tightly designed balance: give drug makers enough time to earn back their investment, then open the door wide for cheaper generics. The key to this balance? The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984. Named after Senators Orrin Hatch and Henry Waxman, this law didn’t just tweak patent rules - it rewrote how new drugs enter the market.

The 20-Year Clock - But It Starts Before You Even Sell the Drug

Most people think a pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years. That’s true - but it starts ticking the day you file the patent, not when your drug hits shelves. Because clinical trials and FDA approval can take 8 to 10 years, the real window to make money is often only 10 to 12 years. That’s not enough to recover costs, let alone fund the next breakthrough.

That’s where patent term restoration comes in. Hatch-Waxman lets drug companies extend their patent by up to five years to make up for time lost during regulatory review. This isn’t a free pass - it’s calculated, capped, and only applies to one drug per patent. It’s a fair trade: more time to profit, in exchange for faster generic access later.

The Orange Book: The Rulebook for Generic Entry

Every approved drug in the U.S. gets listed in the FDA’s Orange Book. This isn’t just a directory - it’s a legal map. Brand companies must list every patent they believe covers their drug: the active ingredient, how it’s made, how it’s taken, even the pill’s coating.

Generic manufacturers study this list before they spend millions developing a copy. If they see a patent they think is weak or invalid, they can file what’s called a Paragraph IV certification. This is a legal challenge - a declaration that the patent doesn’t block them. Once filed, the brand company has 45 days to sue for infringement. If they do, the FDA can’t approve the generic for up to 30 months. That’s a huge delay - but it’s intentional. It gives innovators time to defend their rights without blocking competition forever.

Why the First Generic Gets a 180-Day Head Start

Here’s the real incentive: the first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusivity. No other generics can enter during that time. That’s not just a reward - it’s a financial jackpot.

Why? Because of state laws that force pharmacists to substitute generics when possible. If you’re the only one on the market, you can charge nearly as much as the brand - sometimes 70% less, but still far more than what comes later. That’s why companies risk millions in lawsuits. The payoff is huge. In 2023, over 97% of generic applications still used this route, according to litigation analytics from Lex Machina.

What Happens When the Patent Expires?

When the exclusivity ends, prices don’t just drop - they collapse. After Eli Lilly’s Prozac patent expired in 2001, the company lost 70% of its U.S. market share and $2.4 billion in annual sales. That’s the power of competition.

Generic drugs cost 80% to 85% less than branded ones. In the U.S., generics make up 91% of all prescriptions but only 24% of total drug spending. That’s $373 billion saved every year, according to FDA data from 2022. Ibuprofen, once sold as Brufen, became a penny-a-pill after patents expired. Same active ingredient. Same effectiveness. Just no marketing budget.

Each new generic that enters pushes prices down further. By the time five generics are on the shelf, the price can be 90% lower than the original brand. That’s the system working as designed.

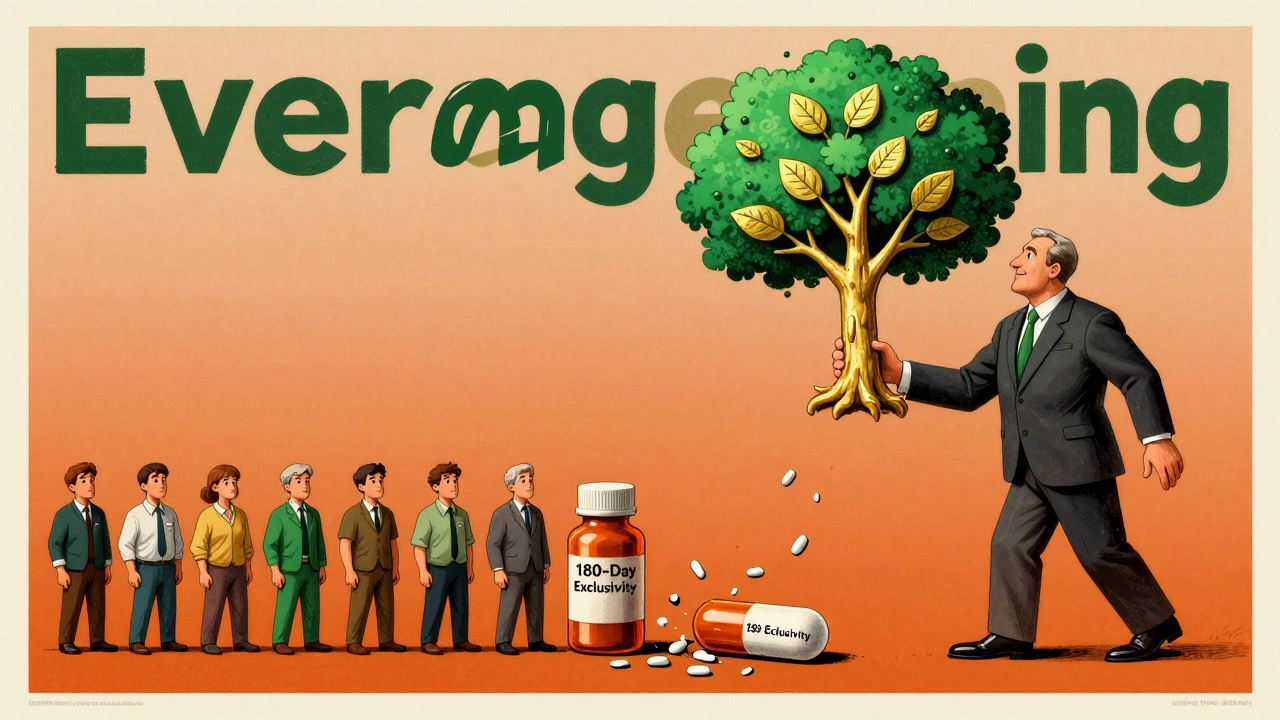

The Dark Side: Evergreening and Patent Thickets

But not everyone plays fair. Some companies use a tactic called evergreening. Instead of inventing new drugs, they file patents on tiny changes - a new dosage form, a slightly different release mechanism, even a new color. These aren’t breakthroughs. They’re legal tricks to extend monopoly control.

Humira, a blockbuster arthritis drug, had 241 patents across 70 patent families. That’s not innovation - that’s a wall. It kept biosimilars out of the U.S. until 2023, even though they were available in Europe since 2018. The European Commission calls this kind of behavior an abuse of market power. In the U.S., it’s legal - for now.

Another tactic? Product hopping. A company slightly reformulates a drug, then pushes doctors and patients to switch. When the old version’s patent expires, the new one is still protected. The CREATES Act of 2022 cracked down on this by forcing brand companies to supply samples to generic makers - a key step they used to withhold to delay competition.

Pay-for-Delay: When Generics Get Paid to Stay Away

One of the most controversial practices is pay-for-delay. A brand company pays a generic manufacturer to delay launching its cheaper version. It sounds like a cartel - and it is. The FTC estimates this costs consumers $3.5 billion a year.

These deals used to be common. Now, courts and the FTC are cracking down. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act aims to ban them outright. But they still happen - quietly, in complex settlements that hide behind legal jargon.

Biologics and the New Frontier

Biologic drugs - made from living cells, not chemicals - are the next battleground. They’re complex, expensive, and hard to copy. The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was supposed to create a clear path for biosimilars, like generics for biologics.

But a 2017 court decision in Amgen v. Sandoz threw a wrench in it. The court ruled that brand companies didn’t have to share their manufacturing secrets with generics during the patent dispute process. That created chaos. Biosimilar entry has been slower than expected, and the rules are still being fought out in court.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Brand drugmakers argue they need strong patents to justify investing $83 billion a year in research. Without that, they say, no new cancer drugs, no Alzheimer’s treatments. That’s true - innovation doesn’t happen without risk and reward.

But generic manufacturers point to the numbers: from 2010 to 2020, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $2.2 trillion. That’s not just savings - it’s access. A diabetic who can’t afford insulin today might be able to afford it tomorrow - if the patent expires and generics come in.

The system isn’t perfect. It’s full of loopholes, delays, and legal games. But its core goal remains: protect innovation, then unleash competition. The real question isn’t whether patents should exist - it’s whether we’re letting them be used to delay access too long.

What’s Next?

Prescription drug spending hit $621 billion in 2022 - 22% of all U.S. healthcare costs. That’s unsustainable. Congress is debating more reforms: faster generic approval, tighter rules on evergreening, and stronger penalties for pay-for-delay deals.

One thing is clear: as long as patents are the engine of drug development, generics will be the brakes. The challenge isn’t to eliminate one or the other. It’s to make sure the system doesn’t let the brakes get stuck.

How long does a pharmaceutical patent last?

A pharmaceutical patent lasts 20 years from the filing date. But because drug development takes 8-12 years before approval, the effective market exclusivity is usually only 10-14 years. The Hatch-Waxman Act allows patent term restoration of up to five years to compensate for regulatory delays.

What is the Orange Book?

The Orange Book is the FDA’s official list of approved drug products with their patent and exclusivity information. Brand manufacturers must list patents they believe cover their drug. Generic companies use this list to decide whether to challenge a patent before launching a copy.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal notice filed by a generic drug company claiming that a patent listed in the Orange Book is invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. This triggers a 45-day window for the brand company to sue. If they do, FDA approval of the generic is automatically delayed for up to 30 months.

Why do generics cost so much less than brand drugs?

Generics don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials because they prove bioequivalence to the brand drug. They also avoid massive marketing and R&D costs. As a result, they typically cost 80-85% less. With multiple generics on the market, prices can drop by 90%.

What is evergreening in pharmaceutical patents?

Evergreening is when a drug company files new patents on minor changes - like a new pill coating, dosage form, or delivery method - to extend market exclusivity beyond the original patent. This delays generic entry without adding meaningful therapeutic benefit. It’s legal in the U.S. but criticized as anti-competitive.

What’s the difference between a generic and a biosimilar?

Generics are exact chemical copies of small-molecule drugs. Biosimilars are highly similar but not identical copies of complex biologic drugs made from living cells. Because biologics are harder to replicate, biosimilars require more testing and face longer approval timelines. The BPCIA governs biosimilar entry, but legal uncertainty has slowed their adoption.

Do pay-for-delay deals still happen?

Yes, though they’re less common than before. Courts and the FTC have cracked down, and new laws aim to ban them. But some deals still hide in complex settlements. The FTC estimates these agreements cost consumers $3.5 billion a year in higher drug prices.

12 Comments

Shannon Gabrielle- 2 December 2025

So let me get this straight-we spend billions to invent a drug, then let some suit in a suit factory copy it and sell it for pennies? Classic American innovation: build the castle, then invite the peasants to live in it for free.

Patents aren’t monopolies-they’re survival tools. If you can’t profit from your 12-year grind, why bother?

The system works. The real criminals are the ones who think ‘fairness’ means stealing R&D.

ANN JACOBS- 2 December 2025

It is truly remarkable, and indeed profoundly encouraging, to observe the intricate and carefully calibrated equilibrium that has been established within the pharmaceutical patent ecosystem-a system that, while imperfect, nonetheless represents a noble synthesis of incentivized innovation and equitable public access.

One cannot help but admire the foresight of the Hatch-Waxman Act, which, through its nuanced provisions, ensures that the immense capital and intellectual investment required to bring life-saving therapeutics to market is not merely recognized, but honorably compensated-while simultaneously mandating, with moral clarity, the eventual transition to affordable generic alternatives.

This is not merely policy; it is a covenant between society and science, and we are ethically obligated to preserve its integrity.

Matt Dean- 3 December 2025

You people are acting like generics are some kind of miracle. Nah. They’re just the free ride after someone else paid the toll.

And don’t get me started on ‘evergreening’-that’s just corporate greed in a lab coat.

But guess what? The system still works. The first generic to sue gets 180 days of monopoly? That’s capitalism with teeth.

Let the lawyers fight. The patients win.

Walker Alvey- 3 December 2025

Patents are the opium of the pharmaceutical elite.

You call it innovation. I call it legal extortion.

12 years of clinical trials? That’s not progress-that’s a delay tactic wrapped in white coats.

And the Orange Book? A prison ledger for patients.

They patent the color of the pill. The shape. The fucking coating.

And you call that science?

It’s not innovation-it’s intellectual vandalism.

Adrian Barnes- 5 December 2025

The structural inefficiencies inherent in the current pharmaceutical patent regime are not merely suboptimal-they are ethically indefensible.

The conflation of intellectual property rights with therapeutic access constitutes a market failure of monumental proportions.

While the Hatch-Waxman Act was ostensibly designed to mediate between innovation and affordability, its implementation has been systematically subverted by rent-seeking behavior, particularly through the strategic manipulation of Paragraph IV certifications and patent term extensions.

One must question whether the societal cost of delayed generic entry-measured in preventable mortality, diminished quality of life, and fiscal strain on public health systems-justifies the continued preservation of these mechanisms.

The data is unequivocal: 91% of prescriptions are filled with generics, yet 76% of drug expenditure persists in the branded sector. This is not market efficiency. This is systemic capture.

Declan Flynn Fitness- 7 December 2025

Honestly? I love how this system works.

Big pharma gets their time to shine, then boom-generics flood in and make meds affordable.

And that 180-day exclusivity? Genius. It turns lawsuits into a race, not a stall.

People think it’s shady, but it’s just capitalism with a conscience.

And hey-if you’re paying $10 for insulin now instead of $300? That’s a win. 🙌

Michelle Smyth- 9 December 2025

The entire discourse around pharmaceutical patents is a performative farce, a neoliberal spectacle wherein the commodification of biological life is rationalized under the rubric of ‘incentive structures.’

One must interrogate the epistemological foundations of patentability itself-is a slight modification in dissolution profile truly ‘novel,’ or merely a jurisprudential sleight-of-hand?

The Orange Book functions as a palimpsest of corporate hegemony, wherein the lexicon of innovation is co-opted to mask rent extraction.

And the 180-day exclusivity? A grotesque parody of market dynamics-wherein the first litigant becomes the new monopolist.

It is not progress. It is capitalism’s last gasp before its inevitable collapse.

Linda Migdal-10 December 2025

America invented the modern drug. We funded the research. We approved the trials. And now we let foreign companies and bottom-feeders profit off our sweat?

Patent term restoration? That’s not a loophole-that’s justice.

Let them copy insulin in India. But here? We protect our own.

Stop crying about generics. Start thanking the people who made them possible.

Tommy Walton-12 December 2025

Patents = innovation fuel.

Generics = freedom.

Evergreening = cheating.

Pay-for-delay = crime.

Biologics = next war.

Done. ✅

James Steele-13 December 2025

The entire framework is a beautifully orchestrated dance between capital and public welfare-albeit one where the choreography is increasingly corrupted by regulatory arbitrage.

The Orange Book, while ostensibly a transparent instrument, has become a labyrinthine instrument of strategic obfuscation, wherein patent thickets serve not as shields of innovation but as moats of exclusion.

One must acknowledge the paradox: the very mechanisms designed to accelerate generic entry-Paragraph IV certifications, 180-day exclusivity-are weaponized to prolong market distortion.

And yet, the aggregate societal savings remain staggering.

Perhaps the real failure lies not in the law, but in our collective inability to enforce its spirit.

Louise Girvan-14 December 2025

You think this is about drugs? No. It’s about control.

Big Pharma owns the FDA. The Orange Book? A backroom deal.

Pay-for-delay? That’s the DOJ’s favorite secret.

And don’t you dare think the 180-day window is fair-those companies are bought and paid for.

They’re not competing. They’re colluding.

And you? You’re just a pawn in a game where your insulin is priced by lawyers, not scientists.

Wake up. This isn’t capitalism. It’s a cartel with a patent.

Dennis Jesuyon Balogun-16 December 2025

I come from a country where insulin is a luxury. Where children ration doses.

So when I hear Americans argue about ‘fair patent terms’-I don’t hear justice. I hear privilege.

Yes, innovation must be rewarded. But not at the cost of death.

20 years? Too long.

10 years? Still too long.

What if we capped patents at 7 years post-approval? Let generics in faster. Let people live.

Patents shouldn’t be a death sentence for the poor.

This isn’t about ‘balance.’ It’s about who gets to breathe.