Imagine standing on a bus that suddenly feels like it’s tilting, even though the road is perfectly flat. That unsettling spin is what doctors call vertigo, a false sensation of movement or loss of balance caused by problems in the inner ear or brain pathways that control balance. It’s more than a fleeting dizziness-it can hijack your day and make simple tasks feel dangerous.

Quick Takeaways

- Vertigo is a balance‑related sensation, not the same as light‑headedness.

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV) accounts for nearly 25% of cases.

- Common red flags: hearing loss, severe headache, or sudden onset after head injury.

- Most cases respond to repositioning maneuvers or vestibular rehab.

- vertigo can often be managed at home with proper techniques.

What Exactly Is Vertigo?

Vertigo is a specific type of dizziness where you perceive rotation of yourself or the environment. It stems from a mismatch between signals from the inner ear’s semicircular canals, the eyes, and the brain. When these inputs don’t line up, the brain interprets the world as moving.

Major Causes of Vertigo

Understanding the root cause guides treatment. Below are the most frequent culprits, each introduced with its own microdata markup.

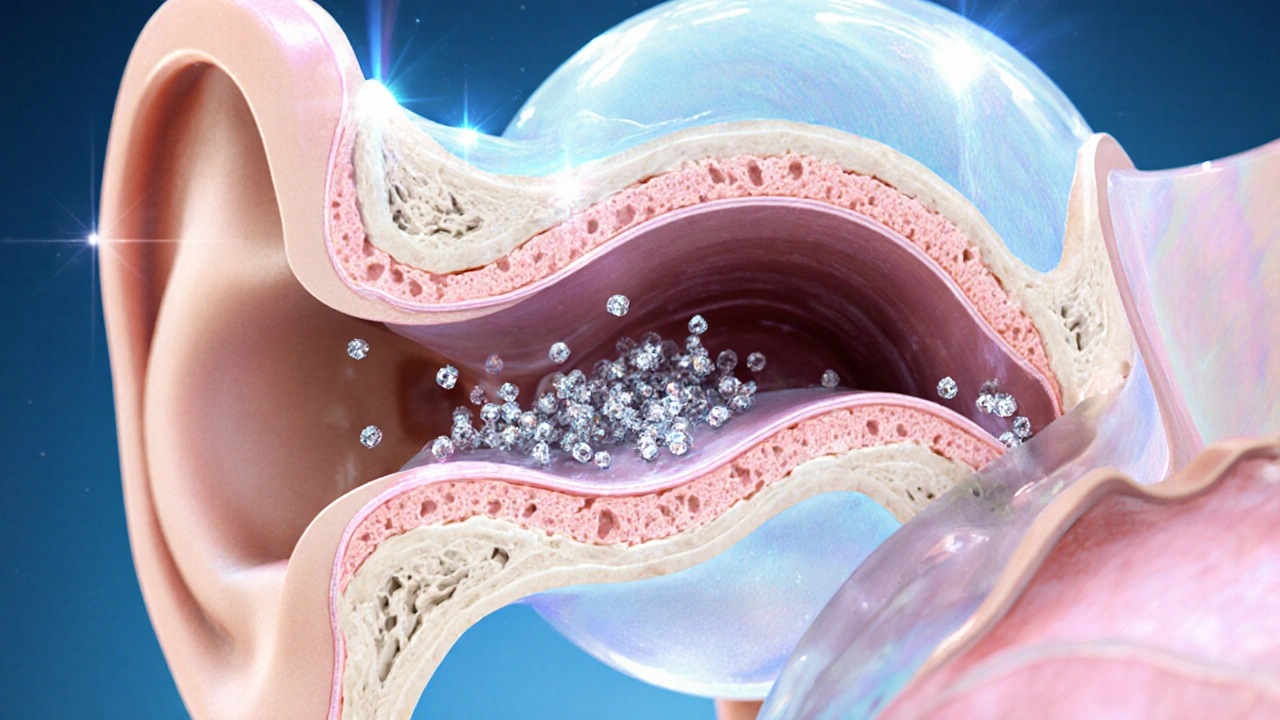

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), a brief, intense spinning sensation triggered by changes in head position

BPPV occurs when tiny calcium carbonate crystals (otoconia) slip into the semicircular canals, usually the posterior canal. The classic trigger? Tilting your head back to look up or lying down.

Meniere’s disease, a disorder marked by fluid buildup in the inner ear, causing episodic vertigo, hearing loss, and tinnitus

Episodes can last from 20 minutes to several hours, often accompanied by a feeling of fullness in the ear.

Vestibular migraine, migraine‑related vertigo that may occur with or without headache

Patients report a sensation of motion along with visual sensitivity. The vertigo can linger for days.

Labyrinthitis, inflammation of the inner ear labyrinth, usually due to viral infection

Sudden onset of intense vertigo, nausea, and hearing changes are typical.

Vestibular neuritis, inflammation of the vestibular nerve, often viral, causing prolonged vertigo without hearing loss

Symptoms can persist for weeks, with unsteadiness being the primary complaint.

Key Symptoms to Recognize

- Spinning sensation (true vertigo) vs. feeling faint (presyncope).

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Unsteady gait or difficulty standing.

- Ear‑related signs: ringing, hearing loss, ear fullness.

- Headache or visual disturbances, especially in vestibular migraine.

How Doctors Diagnose Vertigo

Diagnosis begins with a thorough history and physical exam. Specialists-usually an otolaryngologist, an ear, nose, and throat doctor with expertise in balance disorders-perform a series of bedside tests.

- Dix‑Hallpike maneuver: The patient is rapidly moved from sitting to supine, head turned 45°, to provoke BPPV.

- Head‑Impulse Test: Evaluates the vestibulo‑ocular reflex.

- Romberg and tandem walking tests: Assess static balance.

If needed, imaging (MRI) or vestibular function tests (videonystagmography, audiometry) rule out central causes.

Treatment Options Overview

Therapy hinges on the underlying cause. Below is a quick comparison of first‑line treatments for the most common disorders.

| Condition | Primary Treatment | Success Rate | Typical Recovery Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| BPPV | Canalith repositioning (Epley maneuver) | ≈90% | 1-2 days |

| Meniere’s disease | Low‑salt diet, diuretics, intratympanic steroids | 60‑70% symptom reduction | Weeks to months |

| Vestibular migraine | Migraine prophylaxis (beta‑blockers, CGRP inhibitors) | ~70% improvement | Variable |

| Labyrinthitis / Neuritis | Corticosteroids, vestibular rehab | 80% symptom resolution | 2‑4 weeks |

Beyond these, vestibular rehabilitation therapy, a tailored exercise program that improves balance and reduces dizziness is effective for chronic cases.

Home Management Tips

- Practice the Epley or Semont maneuver at home only after professional instruction.

- Stay hydrated; dehydration can worsen vertigo.

- Avoid rapid head movements-turn slowly when getting out of bed.

- Use a nightlight to reduce disorientation in the dark.

- Focus on a fixed point (the “visual fixation” technique) during an episode to lessen spinning.

When to Seek Immediate Care

If you notice any of the following, call a health professional right away:

- Sudden severe headache, especially with neck stiffness (possible stroke).

- Double vision, slurred speech, or facial weakness.

- Persistent vomiting that prevents keeping fluids down.

- Loss of hearing accompanied by ringing and fullness.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can vertigo be a sign of something serious?

Yes. While most cases are benign, vertigo can indicate a stroke, brain tumor, or inner‑ear infection. Red‑flag symptoms like sudden weakness, vision changes, or severe headache merit immediate evaluation.

How many times can I do the Epley maneuver?

Most clinicians advise up to three repetitions in one session, then re‑evaluate after 24‑48 hours. If symptoms persist, schedule a follow‑up rather than repeat endlessly.

Is there a diet that helps with vertigo?

A low‑salt diet helps reduce fluid buildup in Meniere’s disease. Limiting caffeine and alcohol can also lessen inner‑ear irritation for many patients.

Can medications cause vertigo?

Certain drugs - such as antihistamines, blood pressure meds, or sedatives - may trigger dizziness as a side effect. Review any new medication with your doctor if vertigo starts after a prescription change.

Is vertigo the same as motion sickness?

No. Motion sickness results from a mismatch between visual cues and inner‑ear motion during travel, whereas vertigo originates from an internal balance‑system problem and can occur even when you’re still.

19 Comments

Carl Boel- 6 October 2025

From a neurovestibular standpoint, vertigo epitomizes a pathological mismatch in the sensorimotor integration matrix, demanding a rigorous pathophysiological paradigm shift in diagnostic algorithms.

Shuvam Roy- 7 October 2025

I appreciate the comprehensive overview presented here; it clearly delineates the distinctions between true vertigo and presyncope. The step‑by‑step description of the Dix‑Hallpike maneuver is particularly useful for clinicians. Additionally, the emphasis on hydration and gradual head movements aligns with best practice guidelines. While the article is thorough, a brief mention of vestibular rehabilitation programs could further enhance patient self‑management.

Jane Grimm- 8 October 2025

The exposition, while comprehensive, egregiously neglects the socioeconomic determinants of health.

Nora Russell- 9 October 2025

One must question the superficiality of the analysis; the author glosses over the intricate biomechanics of otoconial migration, thereby betraying an elitist complacency that undermines scholarly rigor.

Craig Stephenson-10 October 2025

Great summary! I’ve found the Epley maneuver works wonders for my patients, and it’s good to see it highlighted here. Keep the practical tips coming.

Tyler Dean-11 October 2025

The medical establishment’s focus on pills is a diversion; look into electromagnetic field exposure for a real cause.

Susan Rose-12 October 2025

Vertigo affects folks worldwide, and sharing knowledge like this helps bridge cultural gaps in health awareness.

diego suarez-13 October 2025

Absolutely agree-simple home strategies can empower patients. Just remember to move slowly when getting out of bed to avoid triggering a spin.

Eve Perron-14 October 2025

Vertigo, as delineated in the article, is a manifestation of vestibular dysregulation that can profoundly impair daily functioning.

The authors correctly emphasize the predominance of BPPV, yet they could have elaborated on the nuances of canalith repositioning efficacy across age groups.

Moreover, the discussion of Meniere’s disease would benefit from a deeper exploration of dietary sodium restriction and its mechanistic basis.

The inclusion of vestibular migraine highlights the intersection between neurology and otology, an interdisciplinary nexus often overlooked.

Clinical practitioners should note that the Dix‑Hallpike maneuver, while a gold standard, may produce false negatives in patients with cervical spine limitations.

Additionally, the role of vestibular rehabilitation therapy as a cornerstone for chronic cases deserves more extensive coverage.

From a pathophysiological perspective, the fluid dynamics within the endolymphatic sac provide fertile ground for future research.

Patients presenting with red‑flag symptoms, such as sudden severe headache, must be triaged promptly to exclude cerebrovascular events.

The article’s tabular comparison is a useful quick reference, yet it could incorporate confidence intervals for treatment success rates.

In practice, clinicians often encounter medication‑induced vertigo, a facet that warrants vigilant medication reconciliation.

Furthermore, the psychosocial impact of persistent vertigo, including anxiety and depression, should be addressed within a holistic treatment plan.

The suggested home management tips are pragmatic, though the recommendation to use nightlights could be expanded to discuss circadian rhythm considerations.

It is imperative that patients receive education on visual fixation techniques, which can attenuate symptomatic spinning during acute episodes.

Future guidelines might integrate tele‑rehabilitation platforms to enhance accessibility for patients in remote locations.

Overall, the article serves as a solid foundation, but the incorporation of these additional dimensions would elevate its clinical utility.

Josephine Bonaparte-14 October 2025

Nice write‑up! :) This info will help a lot of people dealing with dizzy spells.

Meghan Cardwell-15 October 2025

Clinically, the distinction between peripheral and central vertigo hinges on nystagmus patterns; incorporating video‑oculography can sharpen diagnostic precision, especially in ambiguous cases.

stephen henson-16 October 2025

Thanks for the thorough guide! 😊 The tip about focusing on a fixed point really helped me during an episode.

Manno Colburn-17 October 2025

When we contemplate the epistemological underpinnings of vestibular pathology, we must acknowledge that our diagnostic heuristics are but a palimpsest of historical conjecture; yet, the relentless pursuit of neuro‑otologic clarity persists, even as typographical errors infiltrate our manuscripts, reminding us of our humanity within the scientific endeavor.

Namrata Thakur-18 October 2025

What a helpful article! I’ve seen many patients benefit from simple hydration tricks and the night‑light suggestion-small changes, big impact.

Chloe Ingham-19 October 2025

All this “medical” talk is a cover‑up! The real cause is hidden electromagnetic waves from 5G towers-don’t trust the doctors.

Mildred Farfán-20 October 2025

Oh great, another “expert” list. Because we definitely needed more tables to read while feeling like we’re on a carousel.

Danielle Flemming-21 October 2025

Super insightful! I’m curious, has anyone tried the “spinning pizza” visual trick? It’s a fun way to distract the brain.

Anna Österlund-22 October 2025

This post slams the door on vertigo myths-finally, some straight talk that cuts through the nonsense.

Brian Lancaster-Mayzure-23 October 2025

Appreciate the balanced overview. I’ll keep this handy for the next time a patient mentions “the world is spinning.”