When a patient picks up a generic version of their blood pressure pill and suddenly feels dizzy, nauseous, or breaks out in a rash, most people assume it’s just a side effect. But what if it’s not? What if the generic version-though labeled as "therapeutically equivalent"-has a different filler, coating, or release mechanism that’s causing a real, avoidable reaction? That’s where pharmacists come in. Not just as dispensers, but as the frontline defenders of medication safety. And yes, adverse event reporting is part of their job-whether they like it or not.

Why Generic Medications Need Extra Attention

Generic drugs are supposed to be identical to brand-name versions in active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and how they work in the body. But here’s the catch: they don’t have to be identical in everything else. The inactive ingredients-like dyes, binders, or preservatives-can vary. And those little differences? They can trigger reactions in sensitive patients. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that 31% of patients who switched to a generic version of their seizure medication reported new or worsening symptoms. In 14% of those cases, switching back to the brand name resolved the issue. That’s not a fluke. It’s a signal. Pharmacists are often the first to notice these patterns. They see the same patient come back week after week with the same complaint. They hear, "This new pill doesn’t feel right." And they’re the ones who can connect the dots-especially when prescribers assume the generic is a perfect copy.What Counts as an Adverse Event?

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is any harmful, unintended effect from taking a medicine. It’s not just a bad stomach ache. According to the Ontario College of Pharmacists, a serious ADR includes reactions that:- Require hospitalization

- Lead to permanent disability

- Are life-threatening

- Result in death

- Cause congenital malformations

Legal Duty: It’s Not Optional in Some Places

In the U.S., federal law doesn’t force pharmacists to report adverse events. But that doesn’t mean they’re off the hook. Many states have their own rules. In British Columbia, pharmacists are legally required to:- Notify the patient’s doctor

- Document the reaction in PharmaNet

- Report it to Health Canada

What Pharmacists Should Do-Step by Step

Here’s what actually works in practice:- Listen to the patient. Don’t dismiss complaints like, "This one doesn’t work the same." Ask: "When did you start noticing this?" "Did you switch medications recently?"

- Check the prescription. Was there a recent switch to a different generic manufacturer? Look at the pill’s imprint, color, or shape. Even small changes can signal a new formulation.

- Document everything. Record the patient’s symptoms, timing, medication name, lot number, and manufacturer. If you’re in a community pharmacy, use your practice management system. If you’re in a hospital, use the EHR’s built-in ADR module.

- Report it. Use MedWatch Online (FDA’s portal) for U.S. reports. In Canada, use Health Canada’s online form. Some states now integrate reporting directly into pharmacy software-saving 15-20 minutes per report.

- Follow up. Call the patient back in a few days. Did the reaction stop after switching back? Did the doctor change the prescription? That feedback helps build the case for future action.

Why Reporting Matters More for Generics

Think of it this way: if a brand-name drug causes a reaction, everyone assumes it’s the drug itself. But with generics, the assumption is: "It’s the same thing." So when a patient has a bad reaction, no one thinks to question the generic version. Dr. Michael Cohen of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says it plainly: "When patients experience unexpected reactions to generics, pharmacists are often the first to recognize potential bioequivalence issues or excipient-related problems that might not be immediately apparent to prescribers." That’s the gap. Prescribers don’t always know which generic manufacturer their patient got. Pharmacists do. And they’re the only ones who can say: "This batch is different. This isn’t just a side effect. This is a safety signal."

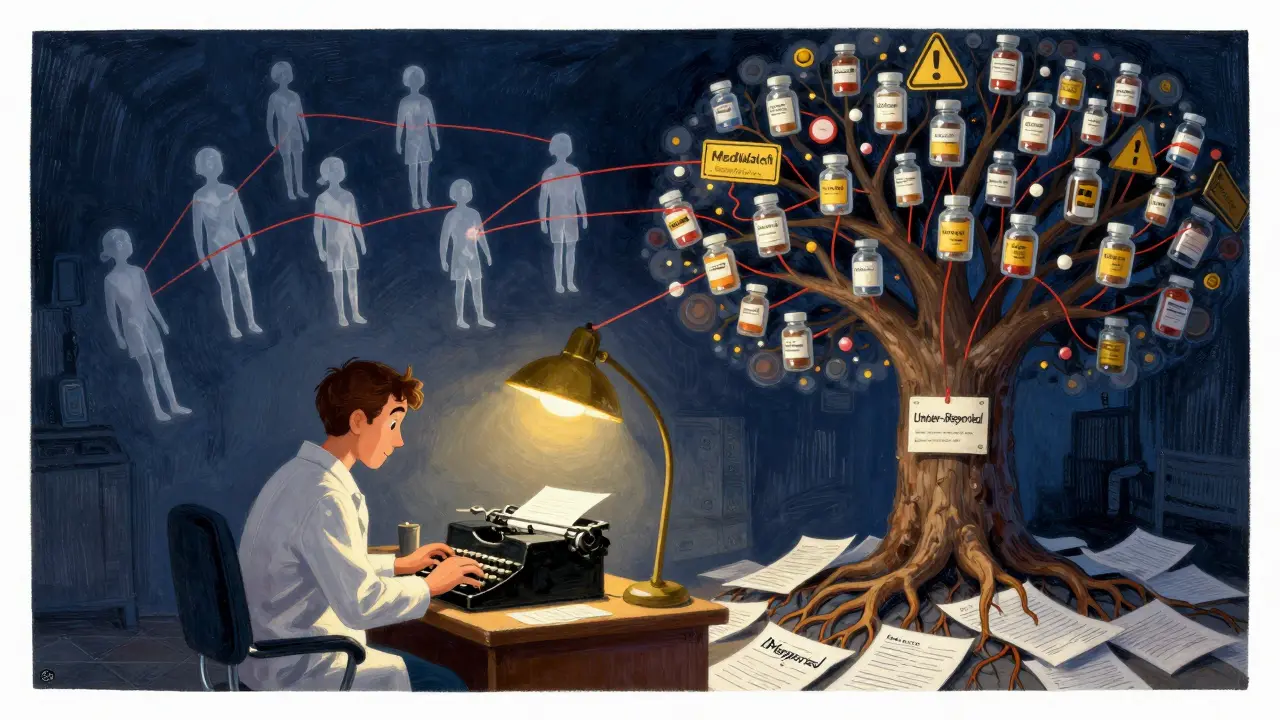

The Bigger Picture: Under-Reporting Is a Systemic Failure

The FDA’s database has over 24 million reports since 1968. But experts believe that represents less than 1% of actual adverse events. Why? Because reporting is slow, clunky, and often seen as "not my job." Pharmacists are stretched thin. They’re filling scripts, counseling patients, managing insurance issues, and dealing with staffing shortages. Adding another task feels impossible. But here’s what’s changing:- The FDA’s Sentinel Initiative is now pulling data from community pharmacies to monitor real-world drug safety.

- California and Texas pilot programs cut reporting time by 40% by embedding forms into pharmacy software.

- Europe made reporting mandatory for all healthcare professionals in 2012. Result? A 220% jump in reports.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re a pharmacist:- Don’t wait for a law to tell you to report. Start today.

- Keep a simple log: patient name (or initials), drug name, manufacturer, reaction, date, and whether it resolved.

- Talk to your pharmacy manager. Ask if your system has an integrated reporting tool.

- Train your staff. Even pharmacy technicians can flag potential reactions.

- Report even the "small" stuff. One report might seem insignificant. Ten reports from ten different pharmacies? That’s a pattern.

- If a generic pill makes you feel worse, say something.

- Ask your pharmacist: "Is this the same as my last one?"

- Keep a medication diary. Note when symptoms started and what changed.

Final Thought: Safety Isn’t a Checklist. It’s a Culture.

Adverse event reporting isn’t about paperwork. It’s about trust. Patients trust pharmacists to know when something’s wrong. Regulators trust pharmacists to speak up when the system fails. And when pharmacists report, they don’t just protect one person-they protect thousands. The next time you dispense a generic medication, remember: you’re not just handing out pills. You’re holding the first key to a safety net that might save a life.Are pharmacists legally required to report adverse drug reactions?

It depends on where they practice. In the U.S., federal law doesn’t require it, but some states like British Columbia (Canada) and New Jersey have specific legal mandates. Even where it’s not required, professional guidelines from ASHP and the FDA strongly encourage reporting, especially for serious or unexpected reactions.

What’s the difference between a side effect and an adverse event?

A side effect is a known, expected reaction listed in the drug’s documentation-like drowsiness from antihistamines. An adverse event is any harmful, unintended reaction, whether expected or not. If a patient develops a rash after switching to a new generic version of a drug they’ve taken for years without issue, that’s an adverse event-even if the drug’s label doesn’t mention rashes.

Can pharmacists report adverse events for generic drugs even if the reaction seems minor?

Yes. Minor but unexpected reactions are just as important. A single report might not mean much, but if multiple pharmacists report the same reaction to the same generic drug from the same manufacturer, regulators can spot a dangerous pattern. That’s how recalls and safety alerts start.

How long does it take to report an adverse event?

It used to take 15-30 minutes using paper forms or online portals. Now, many pharmacy systems integrate reporting tools that cut that time to under 5 minutes. The FDA’s MedWatch Online portal is the most common route in the U.S., and some states have automated reporting built into their pharmacy software.

Why are generic medications more likely to cause under-reported adverse events?

Because of the assumption that generics are identical to brand-name drugs. When a patient has a reaction, prescribers and patients often blame the patient’s condition or other medications-not the generic version. But inactive ingredients (fillers, dyes, coatings) can differ between manufacturers and trigger reactions. Pharmacists are the only ones who typically know which manufacturer’s product the patient received.

What happens after a pharmacist reports an adverse event?

The report goes into the FDA’s FAERS or Health Canada’s database. Analysts look for patterns-like multiple reports of the same reaction linked to one generic manufacturer. If enough reports emerge, regulators may issue safety alerts, require label changes, or even request a product recall. It’s a slow process, but every report adds to the evidence.

Can pharmacists report adverse events anonymously?

Yes. While providing patient details helps with analysis, it’s not mandatory. You can report without names or identifiers. The FDA and Health Canada accept anonymous reports. The key is to include the drug name, manufacturer, reaction, and timing.

11 Comments

Alexandra Enns-25 January 2026

Let me get this straight - Canada has mandatory reporting and the US is still acting like this is optional? We’re the ones with the biggest pharma industry and the worst safety culture. This isn’t about paperwork, it’s about survival. My cousin got hospitalized after a generic switch and the pharmacist just shrugged. That’s not a mistake, that’s negligence. We need federal mandates, not state-by-state patchwork.

Marie-Pier D.-26 January 2026

Thank you for writing this 💛 I’ve been telling my pharmacy students for years: if a patient says ‘this doesn’t feel right,’ BELIEVE THEM. I had a 72-year-old woman come in crying because her new generic antidepressant made her feel like she was underwater. We switched her back - she cried again, but this time from relief. Small things matter. Always document. Always report. You never know who you’re saving.

Heather McCubbin-26 January 2026

Why do we even bother with generics if theyre not actually the same thing like they claim? Big Pharma is just milking the system and the FDA is asleep at the wheel. I bet theyre all in bed with the manufacturers. This is why I only buy brand name now even if it costs 3x. Its not about money its about not dying because someone cut corners

venkatesh karumanchi-27 January 2026

As a pharmacist in India, I see this daily. Patients switch generics all the time - no one checks. But when they get rashes or dizziness, they blame themselves. I’ve started keeping a small notebook - just drug name, manufacturer, reaction. I show it to my team. We’ve flagged three batches already. One led to a recall. Small steps. Big impact.

Sharon Biggins-27 January 2026

i just started my first job at a community pharmacy and this article made me cry. not because its sad, but because i finally feel like my job matters. i used to think i was just handing out pills. now i know im the last line of defense. thank you for reminding me. i’m already logging every weird reaction i hear. even the small ones. one day it might save someone.

John McGuirk-29 January 2026

this is all fake. the real reason generics cause issues is because the government is poisoning us to control the population. look at the dyes they use - they’re the same ones in the water supply. they want us sick so we keep buying meds. you think this is about safety? its about control. and pharmacists? they’re just the foot soldiers. wake up.

Michael Camilleri-31 January 2026

people think reporting is a chore but its actually a moral obligation if you have any dignity left. if you dont report youre complicit. youre part of the system that lets people die because you were too lazy to click a button. your paycheck isnt worth the blood on your hands if you ignore a rash or a dizzy spell. its not hard. its just inconvenient for you

lorraine england-31 January 2026

Just wanted to say I love how this article doesn’t sugarcoat it. I’m a pharmacist in Ohio and we don’t have a mandate, but I report everything. Even if it’s just a weird taste or a headache that started the same day as the switch. I’ve had doctors tell me ‘it’s probably anxiety’ - but I’ve seen the pattern. One report? Maybe noise. Ten reports? That’s a signal. And I’m not letting mine go silent.

Kevin Waters- 2 February 2026

Great breakdown. I work in a hospital pharmacy and we have an automated reporting tool built into our EHR. It takes 90 seconds. I used to skip it because I was busy. Now I do it without thinking. We’ve flagged three generic batches this year alone - one led to a national alert. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the quiet work that keeps people alive.

Elizabeth Cannon- 2 February 2026

i used to think generics were fine until my mom got a rash from one and the pharmacist said 'it's probably just dry skin' i went back with the pill bottle and the lot number and they admitted it was the coating. now i always ask 'which brand?' and i write it down. if you're not doing this you're not trying. it takes 2 minutes. do better.

siva lingam- 2 February 2026

reporting? lol. just give the patient a new pill and move on. who has time for this? the system is broken anyway. why bother?